Our hair loss journeys were markedly different—for Aisha, it was the result of chemotherapy to treat ovarian cancer, and for Ayanna, it was caused by alopecia universalis, an autoimmune condition characterized by the complete loss of hair, including on the scalp, face, and body.

Our mothers instilled in us a deep respect for our elders, our education, and our crowns. Not literal crowns, but the crowns that grew from our scalps. Historically, in Black households, our crowns were an extension of ourselves, our family, our upbringing, and our aspirations. Our crowns demanded time-consuming maintenance, expensive investments, and a vigilant sense of awareness.

Black women have a complicated relationship with their crowns, to say the least.

As Black women in America, our very existence is the resistance. The personal is political and our hair journey is no exception. Having hair, whether long, short, natural or relaxed, has long been considered a critical pillar of femininity. It has been a source of criticism, praise, and discrimination. It has represented the resistance and assimilation.

As young women, we both chose to establish our lives in Boston, and it was there that we first met and bonded over our upbringings, our crowns, and our shared activist spirit. We also shared haircare tips on local braiders and stylists over the years. And as of late 2019, we now share the experience of having lost our crowns to health-related baldness.

For women, unexpected hair loss can be traumatizing. It compromises our self-esteem and chips away at our womanhood. According to the American Hair Loss Association, 40 percent of hair loss sufferers are women. As time has gone on, society has come around to accepting nontraditional hair styles, but complete baldness on women is universally unaccepted—Black Panther’s Dora Milaje aside.

That, after all, is fiction.

Our hair loss journeys were markedly different—one, the result of chemotherapy to treat ovarian cancer, and the other caused by alopecia universalis, an autoimmune condition characterized by the complete loss of hair, including on the scalp, face, and body. While some shave their heads as an expression of liberation, our hair was stolen from us.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Baldness was something that took both of us by surprise. It was a transformative moment not of our own choosing. It was a loss of our crowns, our protection, our safety blankets, an essential part of our Black womanhood, crowns that we had nurtured and tended to our entire lives.

It was jarring. It was disruptive. It felt like a betrayal.

Though the diseases that caused our hair loss weren’t the same, many of the effects we faced were notably similar. There were a lot of tears, mourning the intimate relationship we developed with our hair since childhood. Similarly, we both felt a loss of identity, an identity that took years to develop and to feel comfortable in.

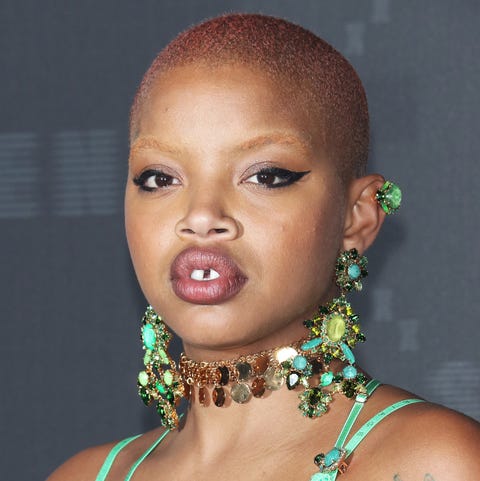

We shared the journey of struggling with self-acceptance following our hair loss. In conventional terms, female baldness may not symbolize beauty nor femininity, but we’d both seen beautiful photos of glammed up, stunning, confidently bald Black women like Danai Gurira, Slick Woods, and Sanaa Lathan. We’ve admired their evenly-colored, beautifully rounded scalps, but our reflections didn’t match those expectations. Our bald heads were porous and bumpy and, because our scalps had never seen the sun before, they were several shades lighter than the rest of our skin.

Coming to terms with a permanent new normal is no easy feat. Luckily, we found comfort in community and in the fact that we were two of millions of women who have lost some or all of their hair. Our new normal presented us with new friendships that taught us that we don’t need hair to rock a crown.

We are still on our journey of accepting the fact that our hair is not the totality of our identity, but that walk has become less lonely thanks to the love and support of our community. Gradually, we adjusted to losing the community that comes with spending hours in the chair at the beauty salon, but we also discovered the unique joys of shopping for a new unit or a wide-brimmed hat with a sister-friend who understood the struggle.

Our experiences are also why we are so passionate about ensuring passage of the Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair Act, or the CROWN Act, long-overdue legislation in Congress that would ban hair discrimination that disproportionately affects Black people. The CROWN Act makes clear that discrimination against natural and protective hairstyles associated with people of African descent, including hair that is tightly coiled or tightly curled, locs, cornrows, twists, braids, Bantu knots, and Afros, is a prohibited form of racial or national origin discrimination in workplaces and schools.

As our society reckons anew with centuries of systemic racism, we cannot ignore the hurt and harm hair discrimination has caused for Black people of every background. In 2017, in Malden, Massachusetts, the Cook sisters–two 15-year old Black girls–faced detention simply for wearing their hair in braids because it violated school dress code. These girls lost classroom time for a minor infraction that did not pose a threat to anyone at the school.

Earlier this month, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the CROWN Act, marking a bold step towards ensuring that people can stand in their truth while debunking the narrative that Black people should show up as anything other than who they are. As we celebrate Alopecia Awareness Month, it is time to declare that no one should be discriminated against because of how they wear their hair, or whether they have hair at all.

By showing up in the world exactly as we are, with or without hair, we send a powerful message that we belong while creating space for others to do the same. Slowly, we came around to accepting our new, bald selves. We believe that speaking up about the pain of hair loss can help others through it, too.

We all deserve to be freed from the shame we collectively feel when our body betrays us. This is about self-agency. This is about power. This is about acceptance. However we show up in the world, we are beautiful and we are enough.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io