At 10 a.m., it’s already as hot as midday. Shaquilla “Shaq” Blake, a rising Black equestrian, finishes feeding the horses at a stable in Massachusetts as part of her student work in exchange for riding lessons. Wearing black breeches and a T-shirt that proclaims “Coffee” in AC/DC font, she squints at the rising sun.

Mornings at the big gray barn start with feedings and end with cleanings. It’s a picturesque scene: The horses—mostly quarters, and some Arabians, Shetlands, and Connemaras—are hosed down with cool water. Everyone gathers around back by the red picnic tables. There, Blake sits with five other barn workers—all of them white. Under the shade, the air thick with the scent of manure, they take a moment to catch their breath before the day’s trail rides begin. As Blake cools off, she feels a tug at her dreadlocks. “Can you feel that?” a giddy voice says from behind her. It belongs to a 13-year-old girl whose profile matches what Blake calls “your typical equestrian”—namely, wealthy and white. Can I feel that?? Of course I can! You just yanked the hell out of my dreads!

This wasn’t the first time Blake felt unwelcome in the sport she loves. At that barn, where she no longer rides, she heard fellow riders use the n-word in front of her. Another time, “Some kids were talking, and one of them goes, ‘Do you smoke pot?’ ” she recalls. “And the other one was like, ‘No, I don’t smoke pot! You think I’m a poor Black person?’ ”

Once, these comments may not have ricocheted beyond the horse-world bubble. But like many elite, largely white institutions—prep schools, opera, theater—the equestrian world is facing its own reckoning with racism. A week after the murder of George Floyd, 17-year-old rider Sophie Gochman, who is white, penned an online essay for the horse-world magazine The Chronicle of the Horse. “We are an insular community with a gross amount of wealth and white privilege, and thus we choose the path of ignorance,” she wrote. A white trainer, Missy Clark, composed a rebuttal. “In our world, some choices are forced because they’re based on the cold hard fact most people can’t afford to do this. It doesn’t mean that it’s fair,” she wrote, “but it also doesn’t mean that it’s discrimination.” Their exchange prompted Lauryn Gray to submit her own story to the publication. The 17-year-old Canadian jumper, who is of mixed race, wrote that “my barn and the circuit I compete on have always been an extremely loving and accepting environment, but…I realize that the same can’t be said about our community as a whole.”

When people talk about the equestrian world in America, they’re usually referring to the one governed by the United States Equestrian Federation (USEF) and tied to major national competitions—and Olympic dreams. The costs to get into the sport (and advance to higher levels), however, are steep, when it comes to both money and time. For example, buying an average amateur horse will set you back $5,000 to $20,000 and up. A top-rated competition like the 12-week-long Wellington horse shows (the Winter Equestrian Festival and the Adequan Global Dressage Festival) in Wellington, Florida, aka the winter equestrian capital of the world, could cost from $10,000 to $65,000 when you factor in the entry fee and the costs of stabling and care. If the dream includes competing at the upper-elite international level with a top horse, add upwards of another $500,000. The average USEF member owns four horses, has an annual income of $185,000, and has a net worth of $955,000. The median household income in America is a little over $60,000 (for Black families, it’s $41,511). Members of the elite club of top-level riders include the children of Michael Bloomberg, Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Bruce Springsteen.

Finances aside, once you’ve ventured into the sport, it’s a whole other hurdle for Black people, especially women. “If you’re not one of them,” says Tayla Moreau of Pine Hill Farm, Blake’s adult amateur trainer, “it’s not like everyone welcomes you with open arms.” Black riders make up less than 1 percent of the USEF, and a Black equestrian has never competed for the U.S. in the Olympics.

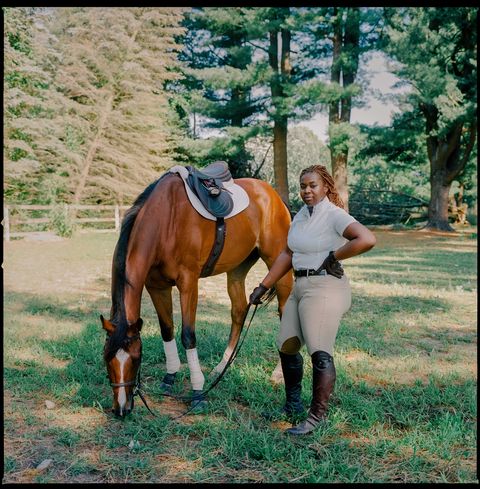

Blake, who spends her days as the lead audio/visual technician at the Federal Reserve Bank in Boston, found ways to make it on her own dime, like buying an off-track Thoroughbred horse. She’s also a working student at Pine Hill Farm in Taunton, Massachusetts, and recently joined USEF (where 89 percent of the members are white and make six figures a year on average) as a “fan member” for $25 annually.

When Blake was first looking into farms, she went on a group trail ride at one barn. Immediately afterward, someone from the barn texted her, saying, “After reviewing [our] lessons and horses available, we do not have the appropriate lesson program to accommodate what you are looking for.” Confused after what she thought was a pleasant riding experience, Blake had a white friend request lessons. And they immediately told her “Absolutely!” Asking around later, she heard that barn had a reputation for not wanting low-income people or people of color to train there.

Scnobia Stewart, a jumper from North Carolina, experienced something similar when she participated in a two-day clinic with Olympian Lendon Gray at a private stable in North Carolina. The 26-year-old worked hard at her Orange County Animal Services day job to save around $800 to travel to the clinic and stable her Dutch Harness horse, Zima. One morning as she braided Zima’s mane, a middle-aged white woman (who Stewart says didn’t work there or attend the clinic) walked up to her and asked if she was there to braid all the horses’ manes. “She looked at me [like I’m] ‘the help,’ ” Stewart says. “It wasn’t the first time [this] had happened to me, and I didn’t want to cause a scene. I let her know that the horse was mine and I was one of the riders in the clinic.” The woman looked at her in disbelief. After sizing up Stewart a moment longer, she walked away.

Philesha Chandler, a Black dressage competitor from Florida, learned the hard way how alone Black people can feel in the sport. When she was a working student at a Kansas riding-lesson and boarding stable, she wasn’t treated like her white fellow riders, and they never stood up for her. White students at the barn were assigned the typical duties associated with a horse barn: tacking, cleaning stalls, feeding and grooming horses, painting fences. Her trainer would ask Chandler to clean her house: sweep and mop the floors, clean the bathrooms, and wash the dishes.

“It was one of those ‘What?’ moments,” Chandler says. “For the trainer to feel I was the best choice for her house chores because of the color of my skin—I was hurt.” Still, she never spoke up, for fear of losing access to the barn and its horses. “There are so many times I experienced racial prejudice in this sport,” she says, that she eventually grew numb. Now a dressage trainer with her own business, she prioritizes mentoring Black kids interested in dressage. “I want them to know that we belong here, and they can do this.”

Veteran show jumper Donna M. Cheek remembers coming up in the ’70s, and microaggressions that were not so micro. “People didn’t want to recognize me because of my skin color,” she remembers. Competing as a hunter—scored at the judge’s discretion—Cheek would get very low marks compared to her white counterparts. “After races, people would tell me, ‘That wasn’t right,’” she says. As a young rider, Cheek often felt unwelcome in riding circles. A white rider she trained with once invited Cheek over to her home for a pool party. Moments after she arrived, her friend’s mom said, “You know how I feel about these people,” and pointed at Cheek. “I wasn’t part of their world, and they made it clear,” she says now.

Her parents received their share of discrimination on their daughter’s behalf. A top trainer from a private riding club in California was interested in working with Cheek. “The trainer was very forthright with my parents and told them, ‘She’s really good, but there’s no way she would be invited into the riding club to train or take a clinic.’ And my parents didn’t tell me about that until decades later.” She says if she could have trained there, that kind of access would have been a game changer.

Despite the challenges, Cheek went on to become the first Black rider to represent the United States in the 1981 World Show Jumping Championships and the first equestrian inducted into the Women’s Sports Hall of Distinction in 1997. She’s now a trainer in Paso Robles, California, and she says there’s still so much work to be done to make the sport more welcoming toward Black people. Now she’s one of those asking the question, How can the future of the sport change so that Black girls who dream of riding can actually participate?

For the sport to truly enter a new chapter, Black riders say, it has to start from within: USEF needs to step up. Riders want to see themselves in magazines, on television screens, and in industry-wide promotions. Investing in inner cities with higher minority populations is also crucial. “If you can’t see people who look like you doing it, living it, how can you dream of becoming that thing?” Blake says.

“People need to be exposed to stories like mine,” says top rider Jordan Allen. “That you can do this and not have all the money.” Allen started riding when she was 7; by 10, her talent caught the eye of well-known trainer Kim Carey. She recommended Allen for the prestigious training center Ashland Farms, where she became a working student. “[Riding at Ashland] exposed me to other barns and to other people giving me horses,” she adds. Without mentorship, scholarship, and access, getting to the top may not have been possible. Allen counts herself lucky: She won the Overall Grand Champion title (in the 3’6″ section) at the USEF Junior Hunter National Championship. But the 19-year-old is usually one of the few Black riders at horse shows and is the only Black athlete on her University of South Carolina equestrian team. Young Black girls reach out to her on Instagram to tell her she’s an inspiration. It’s important for them, she says, to “see me out there.”

USEF says it’s doing the work needed to make the sport inclusive and fair. “The experiences recently shared with us by Black members of our community are heartbreaking and deeply troubling,” said CEO Bill Moroney in a statement to ELLE. “They were also a wake-up call, and we now see US Equestrian has not been a strong enough ally for Black equestrians—especially Black women.” The federation is pledging to provide a special performance-based grant for riders; enact financial support programs that give access and promote education within the industry; implement mandatory antiracist and unconscious bias training for USEF’s staffers and board; and include more Black women in marketing materials. “It’s important that people see themselves,” says Vicki Lowell, USEF’s chief marketing and content officer. “I’m happy that USEF is paying attention and trying to make changes,” Blake says. “I hope it’s lasting change and not just something for the moment.” Meanwhile, she’s raising awareness about the lack of diversity on her blog, theblackequestrian. “It’s going to take all of us staying strong and fighting for the sport we love,” she says.

But that morning outside the barn, she felt all the pressure of being one of the few. Used to double takes and dealing with discriminatory comments, she knew she could handle a little white girl—though she really wanted to scream. “Can you feel this?” the girl asked, pulling harder the second time, making Blake’s head jerk back. Her blood rising, Blake reminded herself where she was and who she was around. “I’ve learned to come off as nonthreatening as possible,” she says, “whitewashing myself in a way, so that people are comfortable around me.”

“Yes, I can feel that,” she calmly told her, smiling. “Now stop touching my hair.”

This article appears in the October 2020 issue of ELLE.