When I was 19, I paid my way to San Francisco with pornography. I answered an ad for the cheapest room I could find, and when the girl who lived there asked me, I lied and said I was straight. I didn’t know anyone. Men or boys asked me to go places, and I went. At a party in the fall, I wore tight red pants and no bra. I drank what was handed to me. I fell asleep on a bed and woke up and this boy was fucking me. His smell and skin and my teeth grinding and I was drunk or high, I don’t know which, and I couldn’t move. I could not make him stop. I passed out again and woke up and his body was there on the bed and I inched away and it was so gray, San Francisco was always so gray, always so predawn, and I did not want to jostle anything, gathered my limbs, my fragile center, slipped out to the gray street and the shivering bus and stepped gently on the stairs up into my rented room and washed myself with hot water and drank hot coffee to burn the inside of me and began the work of pretending it had not happened.

That same year, my boss at the coffee shop left me five messages in three days:

“Hey, just wanted to see if you want to go to that show on Friday at Great American Music Hall.”

“Hey you haven’t called me back so just checking in again to see if you want to go, or maybe get a drink.”

“Hey you know it’s pretty rude of you to just smile at me like that and then not even call me back.”

“You can’t just be nice to people and then act like it doesn’t mean anything.”

“You think you’re so special but you’re not. You should be more careful.”

At work, he did not mention the phone calls. He watched me. He started scheduling me so that I only worked alone. As I wiped down counters, he stood close to me, holding a clipboard, not looking at me, just keeping his big body next to mine.

In Old Town and in Ocean Beach the cops were always watching us. Were always stopping us in the street. Were always making us empty our pockets and backpacks. We felt them coming and we stiffened, tried to duck around corners, tried to avert our faces. At night, they shone their flashlights into our eyes. Some nights they made us stand in a row. They held photos of missing children up beside our faces. We were not missing.

The boy who raped me had paid to see my naked pictures on the internet. He’d done this with his friends, the group of them together at the computer with someone’s brother’s credit card. I knew this because one of them told me. They told me he wanted to fuck me. This was intended as a compliment. I have tried to imagine what they said to each other in that room, hovered over the screen. I can’t hear them. I come up with nothing.

Sex workers, says Catharine MacKinnon, are “the property of men who buy and sell and rent them.” She says that to rape a sex worker means simply to not pay her.

When men ejaculated on me it did not feel like trauma, it felt like money. Like rent. It was not painful. It was not confusing. I did not hate them. I felt nothing about them. I knew what I was agreeing to. I knew what I would have when I walked away. I knew that I owned myself. That owning myself meant having a way to make my money and walk away. That the walking away, more than anything, was the thing that made this work different.

Sex work, tweeted Ashley Judd, is “body invasion.” It commodifies “girls and women’s orifices.” “Cash,” she says, “is the proof of coercion.”

On March 11, 2019, the New York City chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW-NYC) held a protest on the steps of City Hall, demanding the continued criminalization of sex work. Speakers at NOW’s protest called the decriminalization bill that a group of New York sex workers had been organizing toward the “Pimp Protection Act.”

NOW-NYC’s president said, “Yes, you’ve heard it right, the sex trade could be coming to a neighborhood near you.” New York City, she said, could become the “Las Vegas of the Northeast.” As though sex work were not also illegal in Las Vegas.

A small group of sex workers came to counterprotest. They held signs that said, “Sex Workers Against Sex Trafficking.”

The anti-decriminalization protestors stepped in front of them to cover their signs. Speakers said that the sex workers were “ignorant of their own oppression.”

I did not tell anyone that I had been raped. I did not tell anyone and still they said, “What is wrong with you that you allow men to pay to touch you.”

They said, “What happened to you that made you like this?”

I heard these things again and again.

I heard them so often that I feared that they were right, that I had only tricked myself into believing that there was a difference between the things I’d chosen and the things I hadn’t.

In my bed, not sleeping, Adam’s heavy arm over me, my body between him and the wall, I thought: I am broken.

I did not know what I was, and I did not know how to be anything else.

I knew that to become a person that men like Adam could love would mean making myself visibly weak. Would mean performing the kind of weakness that other people could find lovable. Would mean claiming ignorance so they could see me as worthy of being remade.

I knew that the weakness they wanted was nothing like the real weakness inside of me. The real weakness inside of me could only be healed if I trusted my own rules. If I did not give my pain away for other people’s stories.

It was in a porn studio that I first began to feel as though my body was a thing I could love. I did not take the job in order to feel this. I did not even understand it as it was happening. It happened slowly and also all at once. I showed up to shoot and the man that I would be working with asked me, “What are your limits?”

I had no idea what he was talking about.

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

“What do you not want to do?” he asked. And on that day, I could not tell him. No one had ever asked me that question before.

“We’ll try some things,” he said, “and you just say ‘red’ if you want to stop.”

So I tried things. Some of them I liked and some of them I didn’t and some of them I didn’t care about one way or another. Every day when I came to shoot, they asked me the same question: “What do you want to do today? What don’t you want to do?”

Eventually, I could answer. I could make a list. This is what I want. This is what I don’t want.

There was a day when I was tied up, suspended in rope in the middle of a warehouse in downtown San Francisco, and a man was hitting me all over my body with a deerskin flogger. I was in midair, ropes pressed into my hips and thighs and chest with measured tension, leather thudding rhythmically against my back and breasts and I felt a kind of elation, a swelling in my center. I felt strong. I felt myself getting stronger. The scene ended, and they lowered me to the ground and they untied the ropes and blood rushed back into my knees and elbows and I felt suddenly clean. I felt whole. More than whole, I felt unbreakable.

They handed me a check, and it did not feel like coercion, it felt like safety. It felt like I had taken something from them.

“It is impossible,” says Andrea Dworkin, “to use a human body in the way women’s bodies are used in prostitution and to have a whole human being at the end of it, or in the middle of it, or close to the beginning of it. . . . And no woman gets whole again later, after.”

In Los Angeles, the days were all the same but also they were all different. I worked. All of us worked. We lived to work. We called it the “porn dorm” and we called it “porno boot camp” and we got up at 5 a.m. and worked until two the following morning. We worked two-a-days and we worked seven days a week and there was not a single day of the year when someone, somewhere, was not making pornography.

The good days and the bad days were overwhelmed by days when everything went as expected. Days when I showed up and laid out my clothes and we chose something and I put my makeup on and took the stills and waited for male talent or waited for the light or waited for the dialogue and did six positions and a pop and took my check and went home. I felt bored more often than I felt anything else. I felt bored and I felt as though the thing I was inside of was invisible to everyone who was not inside of it.

When I was not working, I was exhausted. I was more exhausted than I had ever been. Some mornings, when it was time to get up to go to work, I cried.

“You cry now, but you’ll cry when you have no money,” my agent said.

I cried and then I went to work.

The day would be good or it would be bad or it would be neither and I would collect my check and my agent would come and pick us up and take us to Jerry’s Deli and we would eat chicken soup and black and white cookies, and I loved him. I loved these women around me, each of them with their bodies like weapons. I felt as though I did not belong anywhere but there.

I’ve rarely talked about my rape and I’ve rarely talked about violence I’ve experienced while doing sex work. I have not talked about these things because I am afraid. Because I know how stories like mine get told. Because I know exactly how good anti–sex work “feminists” are at carving out the pieces of our stories to make them mean something else, something less complicated and more easily sold. I know how good they are at flattening us, at excavating our experiences to make stories that are only an imitation of the things we’ve lived. I know how good they are at making us no longer human but symbols of this thing they call womanhood. This thing they’ve made that I do not see myself in.

I’m afraid, but also I’m angry. I’m angry that I could not talk about violence without fueling descriptions of me as an object, written by women claiming to be my allies. I have survived violence in sex work and also I have chosen again and again to do this work. I have performed sex and femininity and also I am not a symbol of anyone else’s womanhood. I have been poor enough that sex work seemed like a gift, poor enough that sex work changed my power in the world by giving me the safety that money gives. To say that I needed the money is not the same as saying I could not choose, and to say that I chose is not the same as saying it was always good. I have been harmed in sex work and I have been healed in sex work and I should not have to explain either of those experiences in order to talk about my work as work.

“Women must be heard,” says Ashley Judd. And I know that when she says women, she does not mean me.

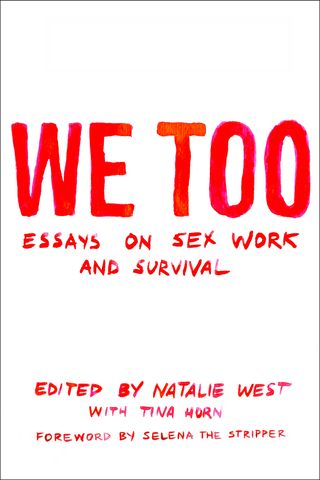

Excerpted from the book We Too: Essays on Sex Work and Survival, edited by Natalie West, with Tina Horn. The essay “When She Says Woman, She Does Not Mean Me” Copyright © 2021 by Lorelei Lee. The collection, published by the Feminist Press, is out now.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io