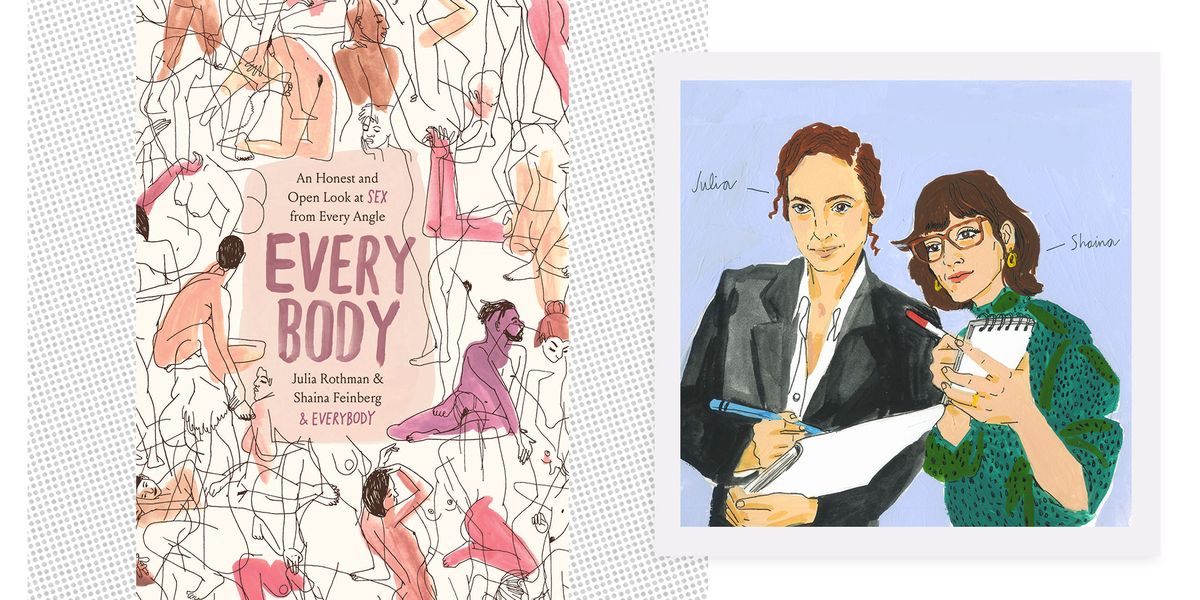

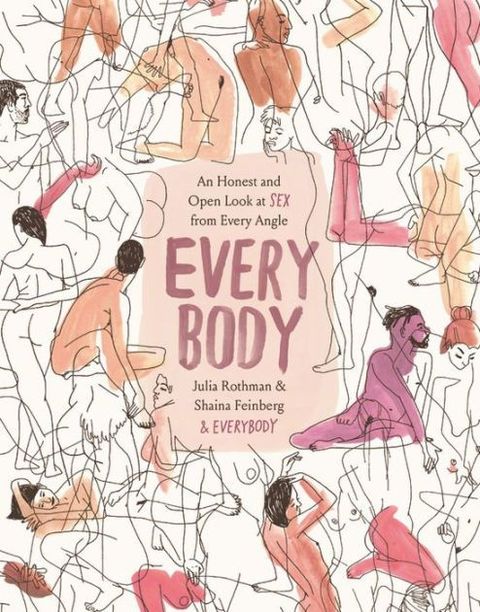

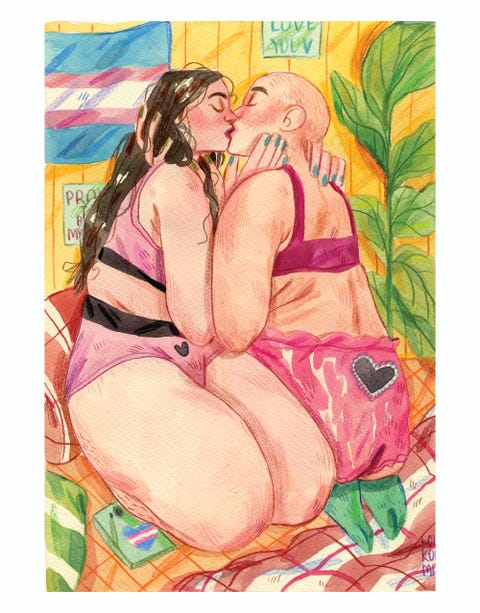

Every Body, a new book from illustrator Julia Rothman and writer and filmmaker Shaina Feinberg, is an inclusive, awkward, tender, silly, discomfiting, emotional, and, above all, candid collection about what it means to be a living person. Vignettes about sexual experiences—culled from impromptu on-the-street interviews and anonymous online submissions—are paired with a range of personal essays, discussions with experts, and erotically-charged art. The book addresses a wide range of experiences, from being horny to unlearning religious inhibitions to drunk sex to watching porn to enduring a miscarriage, all while demystifying stigmas and clichés, normalizing uncertainty, acknowledging trauma, and celebrating desire and playfulness.

Rothman and Feinberg, who have a New York Times column about money called Scratch, are also close friends. ELLE.com Zoomed with the duo to discuss creative collaboration, being a good listener, and how people are waaaaay coyer about money than sex.

How did you meet and start working as a duo?

Rothman: A friend of ours was filming a video and I met Shaina there. I was kinda shy, and Shaina came up to me and said, “Hey! How’s it going?”

[Both laugh]

Feinberg: I saw Julia and I could tell…she felt very New York-y to me, so I was like ‘Oh! Let me strike up a convo.’

Rothman: I ran into you a few times and then invited you to a party. And then—she asked me to do a drawing for one of her films. We started doing more projects together. Shaina wanted to do this thing about how there were no women directors nominated for Academy Awards one year, so I illustrated the piece and she wrote it. And we’re like, ‘Hey, let’s do more of that!’ We did another one for Cup of Jo, and then I was approached by the New York Times to do a column. I was like, I’m going bring Shaina on with me. We like to say the column is basically about small businesses and big personalities.

Feinberg: We were already working on Every Body at that point.

Rothman: That’s true—I brought her on to help me with the book before the Times.

Feinberg: We started the book in April [2019], but the Times didn’t start until August. I think that’s part of why it made sense—we’d already been working so much in concert, as they say.

Rothman: I needed someone who could help me organize and edit. Shaina can come up with crazy ideas I would never do; she has a different brain than I do. I had made a website that I was using to collect stories for the book. I felt the stories were all coming from one type of person: a white woman around my age. I told Shaina I wanted stories from more people and she was like, “Let’s just go on the street and talk to people.” I would never have done that on my own, or even thought of it. That really changed the entire project, which was wonderful. We did it in New York and went to New Orleans and collected a lot of stories.

Feinberg: For Scratch, we were going on the streets and asking people how much debt they’re in. It was similar, going to ask people about sex.

Rothman: People were more scared to talk about debt than they were to talk about sex.

Feinberg: Way more.

Rothman: People did not want to say how much they owed, but they were like, “Let me tell you about my threesome.”

Did you have ideas about what you wanted to cover, or did the conversations and encounters shape the book?

Rothman: The stories informed the topics. There were stories we heard that made us realize, we didn’t think of that. We had made a list of everything we wanted to cover, but then there were things like pegging—we didn’t think a bunch of men would tell us they wanted to do that.

Feinberg: We checked off so many things we wanted to get but were just not hearing about certain things, so we were like, we have to make sure to ask people about this.

Rothman: Like menopause. We actively looked to talk about that, because nobody was offering that information. We had to target talking to some older people.

Feinberg: When older women would talk to us, it was more about memories, like when they had sex in 1971. So when we talked to them, we would ask pointedly, “Have you gone through menopause? What was that like?”

Rothman: The most common thing people wanted to tell us about was sexual assault. So many people couldn’t wait to tell us what had happened to them, which was really hard. Also vaginismus, which is when your vagina tightens involuntarily and nothing can go up and people don’t know why it’s happening to them. And women still being virgins when they’re in their 30s and 40s. It felt like an overwhelming number of stories on those three topics.

I imagine you had a copious amount of material. How did you narrow it down?

Feinberg: We went through it a million times. The first time, it was almost all yeses. The noes would be like, “This makes no sense, actually.” We had to say “maybe” to some of them.

Rothman: Ultimately, it came down to getting a diverse group of people. We took statistics. It was anonymous, but we asked about ethnicity, religion, etc. on the website. If we had five stories about vaginismus, and four women were 40 and white and one was 20 and Black, we made sure [the latter] was in there, and that it was a good story—it was weighing all those things.

How did you balance the anonymous narratives with the writers and illustrators you purposefully assembled?

Feinberg: With the essays and interviews, we made a dream list. Like when you’re making a book about sex, you want to talk to Betty Dodson. She just passed, but she was an amazing sex educator for generations.

Rothman: We wanted some funny people and some serious experts. We wanted some sex workers. One guy uploaded his experience onto the website and it was so good, we decided to pay him as an essayist instead of considering him an anonymous anecdote.

Feinberg: Some of it was, we want that writer or interview; some of it was, we want that topic.

Rothman: I’ve done a lot of books and organized and curated lots of illustrated compendiums. For this, I looked at art that had already been done that was sex-related and asked to reuse it for a fee. The art doesn’t relate to the stories. The stories are separate and the illustrations are their own voices.

Feinberg: That’s what it feels like when you flip through and see the illustration “Pardon my hard-on.”

Rothman: I was inspired by how the New Yorker does their spot illustrations. They tell their own story. I reached out to friends, which is the best, and new people to me. Instagram makes it feel like everyone’s so close to each other. But I was, again, looking for a diversity of styles and backgrounds—making sure it had a range.

In addition to statistical diversity, you mention needing tonal diversity in the book—that you had to fish for more positive stories because negative stories were so recurrent.

Rothman: There were so many sexual assault stories. It was draining. I remember when I first read some on the website and cried. I was so upset and not able to sleep. There were some where I was like, I want to reach out to this person and say something but I can’t, but I’m feeling all these feelings about it. I want to say, “Sorry, and it’s okay, and I hear you and I see you.” There was nothing I could do—it’s someone submitting a story to a site. On the street, when people would talk about a terrible thing, we would ask, “Do you also have a good thing that’s happened?” or, “What do you like about your body?”

From the sheer cumulation of stories, did you see patterns emerge? Did you arrive at any sociological or anthropological conclusions?

Rothman: I came away with: Everyone feels alone and like they are weird and different from everyone else. But they’re not.

Feinberg: There’s an interview with Eric Garrison, who’s a forensic sexologist, and he says basically everyone has one question: “Am I normal?” He tries to reframe it as, “Everything is natural and on a spectrum.” What we came away with is, people genuinely wanted to know if what they feel is okay. And yeah, it is.

Rothman: We’re not doctors, and we’re not experts, we’re not therapists. We’re trying not to have judgment. I remember once by NYU, a young woman sat and told me, “I don’t know who I’m attracted to; I can’t tell if I like men or women, and I’ve never had an orgasm.” I can’t say, like, “That’s okay!” I just listened, you know? But I want to say: “That’s okay! Maybe you need to do some exploring on your own and touch yourself.” It was really hard. If you want something overarching: “Everybody is struggling.”

Feinberg: I think everyone is questioning. Everyone is curious. We weren’t giving advice. But my general take from the whole thing was that everyone is struggling—the person next to you or across from you. We all have these bodies, and we’re doing stuff to them.

Rothman: We’re all trying to understand our relationship to them.

Aside from finding enormous amounts of empathy, has this project pushed you in any new direction, whether it’s your own personal reflection or how you will tackle future projects?

Rothman: I feel like I have yet to find out how this project affected me personally. In terms of work, I realized how much I like talking to strangers. Doing the Times column—it’s my very favorite thing to do, ever. There’s definitely going to be more of that: talking to people and listening to what they have to say, all kinds of people that are really different from us. It feels exciting. It’s like an addiction. I can’t wait until we do it again.

Feinberg: For me personally, I have struggled with body dysmorphia since I was in sixth grade, and working on this book definitely helped me. I felt like I was privy to so many people’s relationships with their bodies. And seeing and hearing about so many kinds of bodies helped me rethink and see that we’re all just bodies, and it’s cool.

Shaina, you discuss this in the conclusion.

Feinberg: It’s so easy, especially as neurotic [slips into accent] “New Yawkahs,” to get out of your body and just be in your brain. This book really helped me to be like, “Oh yeah, I have boobs—let me love them!” Or whatever.

Rothman: We spoke with somebody who had breast cancer, somebody who has a colostomy bag…there’s so many things people are dealing with.

At the start of each section of the book, there are snippets of dialogue between the two of you. How did those come about?

Rothman: Our voice is just to talk back and forth. So we asked each other, “What would you say?”

Feinberg: Some of it was natural. But also I was like, is this too silly for words?

It was grounding! Amongst all these disparate stores, the reader comes back to you as the trusted guides. And you feel the friendship too, which is so endearing.

Rothman: When we met, we were, like, [claps]: done. It wasn’t like, “will we be friends?” It was like: ‘we’re friends.’ It’s a New York Jewish thing. We’re familiar with each other.

Feinberg: It was so easy. With gathering sex stories, there’s a lot of emotion we’ve shared. With Scratch, there’s a lot of things that are—

Rothman: —stressful. Deadlines…

Feinberg: …or someone who shows us their gun in their pants when we’re interviewing them! Like, we were fine, but still, you’re like: let’s wrap this up!

Rothman: [Laughs] We’ve experienced a lot of things together.

Feinberg: And we’ve spent a lot of time together. There’s no TMI anymore, you know?

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io