Growing up, I remember a statue in the house, probably about six feet tall. Beautifully carved, it depicted a woman with a basket on her head, walking hand in hand with a child. Seamlessly multi-tasking, she was carrying, caring, and moving forward. My mother made sure her six daughters knew about the contributions women, Islam, and the African Diaspora made to the world. We lived in a household with an instinctive educational curriculum. It wasn’t overt or formal, but rather a continuous flow of love and knowledge. Because of these teachings, my sisters and I had a solid sense of ourselves. We loved ourselves.

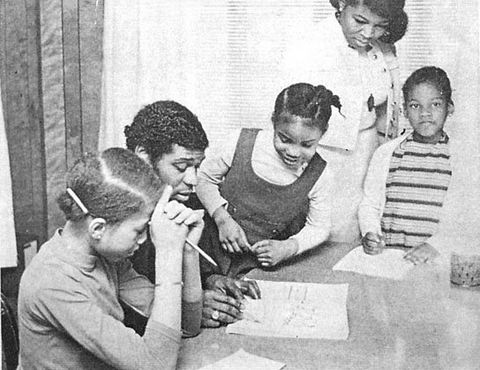

When I was around the age of 7, my mother welcomed Shaykh Ahmad Tawfiq into our home to serve as a tutor to my sisters and me. This is probably where I first got the notion of a curriculum and the radical idea that people learn when they can identify with the characters and concepts presented to them. Shaykh Ahmad Tawfiq would teach us about Africa, telling stories that unraveled with beauty and color. He brought to life the ancient kingdoms of Futajalo, Benin, Ghana, Mali, Egypt. We learned Arabic, and of the ancient University of Timbuktu, a great center for African scholarship built long before European universities. We learned about refined and industrious African people who were scholars, priests, and farmers. I knew where I stood in the large tides of history. But when I went to school, I grew confused. What I was taught there was drastically different from what I learned at home.

The omission of Black, Indigenous, Brown, Asian, and Latinx history is not incidental. These exclusions distance people from their own heritage, their own lineage, and ultimately, their own sense of self. A whitewashed curriculum enforces the myth that there have never been scholars, thinkers, innovators, caregivers, iconoclasts, artists, and revolutionaries across these various identities. Consider, for example, the ancient African kingdoms that were full of immense progress, scholarship, and knowledge. If we learned about them in the same way we learned about ancient Greece and Rome, we would appreciate the present complexity of Black civilization and negate the teachings of biased and inherited hate and discrimination. We would teach respect.

I became a teacher because education is a natural place to channel compassion. What I’ve often seen in our young people and students, whether at the youth detention facility where I mentored or in the group home where I taught, was an emptiness and disconnect from what they were learning. There was no investment in ensuring they identified with the curriculum. In February of 1926, Carter G. Woodman launched the first Black History Week. It’s unfortunate that anyone had to do that, to create a period of time designated to think about Black history. African American history is American history. Though the initiative was first created to highlight the celebration of Black achievements, we’re in a different world today than 1926. Surely, almost a century later, Black history should not be segmented from how we think about American history. It should be baked into the curriculum.

Who are we, and what is our value system? Learning about our history prompts this sort of self-inquiry. We need to decentralize whiteness and Western versions of history from the way we conceptualize our country and our society. To learn about the flow of history—the real, not whitewashed or glossed-over history—is to learn about personal and cultural values, and from this reflection, we can identify action we can take to work towards a harmonious society. When we talk about slavery, or the Jim Crow laws, or the Tulsa Race Massacre of Black Wall Street, we need to identify these moments as just as American as the Boston Tea Party. If we do that, if that history is brought into the present, then more citizens would understand the necessity for reparations. This sort of education ensures we’re instilling a value system of truth, honesty, and human compassion into our young people. Education and justice are synonymous. We’re investing, as a country, $81 billion a year in the incarceration system. What if we invested that money into the education system instead?

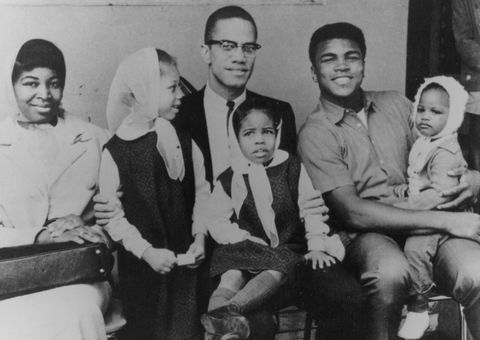

Today, I teach a course at John Jay College of Criminal Justice called “Perspectives on Justice in the Africana World.” As I tell my students, our class is about encouraging critical thought and critical thinking. It’s a safe space to discuss whatever we’re experiencing; there is no right or wrong answer, and I encourage my students to push through their biases. I ask them to challenge any rigid perceptions they might hold and to see things not as black and white, but from a more flexible, complicated moral perspective—a perspective of mutual care as it relates to historical fact. It has been wonderful, beautiful, and intimate to have these students, and this year in particular has brought the material of my course into a sharper light. The prevalence of the criminal justice system in the news and media cycle has brought our history closer to us. This mass unveiling of injustice to many people—though of course, so many of us have long known this injustice—has helped young people see the challenges our foreparents endured in a real way. Historical moments easily passed over during a quick scan of an article or a class presentation are now brought alive. We must relate and react to them in real-time. They are embodied in our current moment. And if our foreparents could take a step forward, like my father did, what can we do?

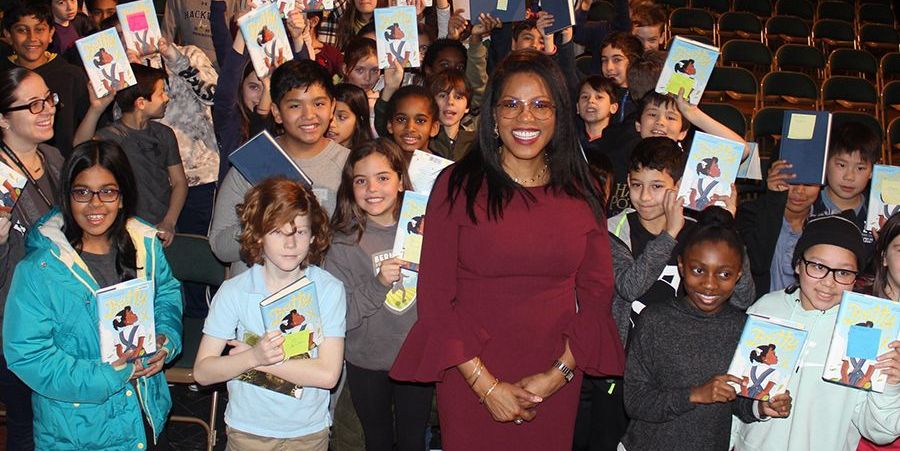

What I’ve learned from my time in education is that my students are yearning for this kind of information. Wanting to learn about history is also wanting to learn how your life can be more purposeful. Education is justice because knowledge of historical fact allows for goodness. When students discover histories full of people like them, who lived full, rich, interesting lives, people who have triumphed and overcome so many systemic obstacles, it gives them an honest, grounded perspective, and the ability to view their own life within that same plane of possibility. Teaching, and specifically teaching critical thinking about history, is a way to help people find their voices. They will know the truth of their history, the accomplishments and contributions of their lineage, and how valuable they all are. A society in which people feel mobilized, centered, and invested with purpose is a society whose citizens can love themselves.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io