South Korea has quietly become Hollywood’s biggest competitor, churning out wildly popular music, TV dramas, and beauty and fashion trends with global appeal. This week, ELLE celebrates the K-World we’re all living in.

When the pandemic brought international travel to a halt and forced the nation to shelter in place, many leaned on entertainment to explore the world beyond the confines of their homes. And perhaps no country has shone brighter in the global spotlight over the past year and a half than South Korea. K-pop artists such as BTS and Blackpink became household names as people spent more time online. Korean food exports—greatly boosted by social media posts from Asian celebrities and the popularity of the film Parasite—hit a record high, with the U.S. becoming the top importer of Korean food in 2020, while Korean food trends like mukbang and dalgona coffee provided welcome quarantine distractions. And as viewers ran out of shows to watch, many of them stumbled upon Korean dramas—and have been hooked ever since.

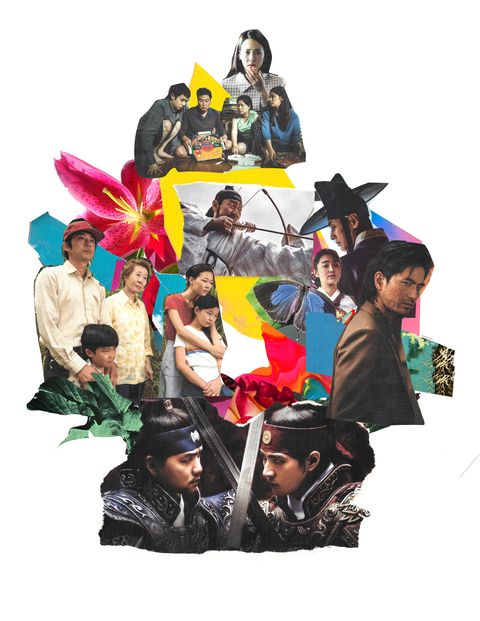

For the unacquainted, Korean dramas—K-dramas for short—are South Korean scripted TV shows. Sometimes they’re referred to as Korean soap operas, but that description is misleading because K-dramas actually encompass a wide range of genres, from sci-fi and romance to horror and period pieces and everything in between. Most consist of a finite number of episodes (often between 16 and 24, though some—especially family-oriented and historical dramas—run for 50-plus) and are usually completed in a single season, with a few notable exceptions (more on that later).

K-dramas are generally known for having high production value, intense and often engrossing storylines, and quality acting that helps build an emotional connection between the characters and the audience. They also tend to consist of more PG-friendly fare than western TV shows (nudity and sex are practically nonexistent, for example), rendering K-dramas more palatable for a wider range of age groups and countries, especially those that are more socially conservative. At the same time, the bold and skillful storytelling with which K-dramas tackle societal issues, personal struggles, and universal themes such as family, friendship, and love make for thoughtful content that resonates with audiences across geographical borders. To put it plainly, K-dramas make us feel less alone and often successfully tap into our shared human experiences and emotions.

They’re also somewhat interactive. “Korean creators still make dramas day by day,” says Dr. Dal-Yong Jin, a communications professor at Simon Fraser University and one of the world’s leading scholars on Korean pop culture. If ratings are low, the show’s creators will change the plot, and if ratings are high, they might decide to extend the number of episodes from, say, 16 to 24, Jin explains. This helps ensure that the series in question is well-received by audiences, but also means that episodes are often shot and edited the same week they’re aired. The production is just as efficient as the storyline.

Though K-dramas have recently taken off in the States, they’ve been popular in Asia for years. In fact, K-dramas have long been one of the key drivers of the Korean Wave, or “Hallyu,” a term believed to have been first coined by Beijing journalists in the 1990s to refer to the growing popularity of K-dramas, K-pop, and other Korean cultural exports. Since then, the Korean Wave has rapidly spread to all corners of the globe, but it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when K-dramas began catching on outside of South Korea. Some sources point to the 1997 success of the family drama What Is Love? and the romance Star in My Heart (aka Wish Upon A Star) among Chinese audiences as the starting point of Hallyu; Jin argues that it started even earlier, in 1993, when China broadcasted the Korean drama Jealousy (Jiltu).

The seeds for Hallyu’s growth were planted even before then. According to Dr. Jung-Bong Choi, a former professor of cinema studies at New York University, Korean network executives in the 1980s and 1990s often took business trips to Japan to draw inspiration from the style and structure of the country’s dramas, which “pioneered the 12-episode miniseries format” and included a diverse array of genres.

The South Korean government also helped lay the groundwork for the burgeoning Korean Wave by further developing the country’s broadcasting infrastructure and allowing for programs to compete against each other. “Korea had only three network channels in the early 1990s, but the Korean government decided to allow another network—SBS in 1991—and multiple cable channels in 1995,” says Jin.

In 1993, when South Korea elected its first civilian president in over 30 years, numerous Korean college graduates and young professionals, feeling liberated from decades-long censorship under military rule, took jobs in the cultural sector. As President Kim Young-Sam’s administration ushered in a new era of globalization, many young South Koreans also traveled abroad and brought back what they had learned overseas, contributing to the country’s cultural rebirth.

As Choi points out, while Japan began looking increasingly inward as its economy went into decline, South Korea took the opposite approach. This all coincided with the beginning of China’s own economic rise, which created an enormous demand for pop culture content—and South Korea was there to provide it. China found American TV shows to be incompatible with its values, and it didn’t want to import content from Japan, its former colonizer. But Korean content was in sync with China’s social aspirations, and this turned out to be a huge boon for South Korea’s entertainment industry, Choi explains.

Japan, long regarded to be the purveyor of cool in Asia, wasn’t immune to the K-drama craze either. When the tearjerker romance Winter Sonata aired there in 2003, it became an instant blockbuster hit, attracting over 20 percent of viewers across the country—a figure that was practically unheard of at the time. Scores of middle-aged Japanese women went crazy for Korean actor Bae Yong-Joon, who plays the male lead in the drama, affectionately nicknaming him “Yonsama” (which means “Prince Yong”). The actor’s incredible popularity even led the then-Prime Minister of Japan Junichiro Koizumi to quip, “Yon-sama is more popular than me.” The drama drastically improved the image that many Japanese citizens had of Korea and Koreans and even enhanced the social status of Zainichi Koreans in Japan, who have long faced discrimination and marginalization in Japanese society.

Other K-dramas from the 2000s, such as Autumn in My Heart, Princess Hours, My Girl, Coffee Prince, Full House, cemented the popularity of K-dramas throughout Asia, from Kazakhstan to Thailand to Indonesia and the Philippines. A 2011 report by the Korean Culture and Information Service noted: “In many Asian cities, Korean dramas seem to be influencing lifestyles and consumer behavior, which speaks to their cultural appeal. Many Korean drama fans spend to share the fashion choices of the stylish fictional characters and crave the city life they live.” Thus, South Korea’s spot in Asia’s cultural zeitgeist was solidified.

The K-drama wave expanded very quickly outside of Asia as well, most notably with the 2003 historical drama Jewel in the Palace—the first K-drama to become a truly global hit. Its story of a hardworking woman who rises from humble beginnings to become the first female royal physician during the Joseon Dynasty seemed to strike a chord with audiences around the world, many of whom drew parallels between the drama and their own country’s political struggles and notions of gender roles. The film eventually aired in 91 countries and saw viewer ratings reach 90 percent in Iran, where it sparked a nationwide interest in Korean language and culture and paved the way for the success of other historical K-dramas in the country, including Queen Seondeok and Jumong. The lack of violence and sex in K-dramas helped spread their popularity to other countries across the Middle East, including Egypt, Turkey, Bahrain, the UAE, Iraq, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.

In Latin America, many viewers were drawn to K-dramas largely due to their emotionally charged scenes and intricate plots, which they found similar to their telenovelas. It also helped that South Korean broadcasters purportedly sold some of their best K-dramas to Latin American TV stations for as low as $1 per episode, making them much more affordable than telenovelas, which often cost thousands of dollars per episode. Korean broadcasters’s deliberate approach to promote Korean content throughout Latin America paid off, as many K-dramas such as Stairway to Heaven, My Fair Lady, and All About Eve had higher viewer ratings than local telenovelas. When former South Korean president Roh Moo-Hyun visited Mexico back in 2005, a group of local K-drama fans staged a rally outside his hotel begging him to send Korean actors Jang Dong-Gun and Ahn Jae-Wook on a visit.

Interestingly, the K-drama wave in Latin America has also been bolstered by Latino employees at Korean supermarkets across the U.S. As Korean immigrant communities sprang up around the country in the ‘80s, Korean-owned supermarkets (such as the now ubiquitous grocery chain H Mart) copied K-dramas onto VHS tapes (and later, DVDs) and rented them out to their Korean customers, who sought familiar content from their native country. “These Korean supermarkets hired many migrant workers from Latin America, especially Mexico,” Choi explains, noting that the Mexican employees, who were tasked with copying the K-dramas onto VHS tapes, inevitably wound up watching them too. “Values of loyalty, devotion, and sacrifice have tugged at the heartstrings of non-westerners. That’s the power of Korean drama.”

Thanks in large part to streamers like Viki (acquired by Japanese conglomerate Rakuten in 2013) and DramaFever making it possible for viewers to legally watch Korean content online with English subtitles, K-dramas began gaining momentum in the West during the 2010s. These platforms also formed distribution relationships with Netflix and Hulu, which allowed them to reach even more audiences. After Warner Bros., which had acquired DramaFever, abruptly shut down the service in 2018, Netflix began investing heavily in K-dramas and premiered its first Korean original series, the zombie K-drama Kingdom, in January 2019 to great acclaim.

Then 2020 happened and turned out to be a milestone year for K-dramas. Viki witnessed its North American subscribers grow by 42 percent between 2019 and 2020, while KOCOWA, which offers exclusively Korean content, also saw its content consumption spike during the same period, a fact that product marketing team leader Justine McKay partially credits to the critical and commercial success of Parasite and Minari. “U.S. viewers started seeking out more K-content featuring these amazing actors,” she says.

A spokesperson at Netflix revealed that viewing of Korean content across Asia increased fourfold in 2020 compared to 2019. Notably, the blockbuster rom-com Crash Landing on You stayed in the top 10 in Japan for a whopping 229 days and was the sixth most-watched TV show on Netflix in the U.S. between March 21 and March 27, 2020. Audiences fell in love with It’s Okay to Not Be Okay, which entered the Netflix top 10 last year in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Nigeria, and Russia, as well as multiple countries in Latin America and Asia. The horror K-drama Sweet Home was watched by 22 million subscribers in its first four weeks on Netflix and was ranked #3 on the platform in the U.S. and globally shortly after its release.

Back in 2014, the Korea Creative Content Agency (KOCCA) released a study estimating that approximately 18 million Americans watched K-dramas. One can only assume that figure is much, much higher now.

The K-drama craze has indeed hit a fever pitch, reaching even the most isolated places in the world like North Korea, where bootleg copies of South Korean dramas have been smuggled into the country since the 1990s and Korean pop culture is now viewed as a growing threat to Kim Jong-un’s power. Stateside, K-dramas have spawned American remakes such as The Good Doctor (now in its fifth season) and inspired a number of online communities on Facebook and Clubhouse.

K-dramas have also dramatically (no pun intended) boosted tourism to South Korea, with a 2017 Korea Tourism Organization survey finding that roughly half of foreign tourists in South Korea decided to visit the country after watching Korean dramas and films. Filming locations of hit K-dramas have become popular tourist destinations in South Korea, and beginning in the early 2000s, scores of Asian women—enamored with the strong, handsome, and romantic Korean male leads they saw in K-dramas—have ventured to the country in hopes of dating and marrying a Korean man. K-dramas have also fostered the growth of South Korea’s booming medical industry as countless tourists visit the country every year to undergo plastic surgery in an effort to look more like Korean actors or actresses.

And it seems the global popularity of K-dramas will only continue to grow. Currently, K-dramas on Netflix are dubbed and subbed in over 30 languages, including English, German, French, Swedish, Hindi, Portuguese, and Bahasa Indonesia. The entertainment powerhouse announced earlier this year that it is investing $500 million in Korean content in 2021. Apple TV+ and Disney+ are following suit, with the former adding at least two of its original K-dramas, Dr. Brain and Pachinko, later this year, and the latter working with local producers to create more Korean content.

As K-dramas continue to attract audiences far and wide, will the increased globalization impact the way they’re made in the future? The popularity of American crime dramas like CSI in South Korea has seemingly led to similar fare, such as Stranger and Voice, both of which were huge successes with domestic audiences.

In a world where an increasing number of viewers are watching K-dramas, their tastes and preferences inform the type of content being made. “Young audiences now lead the trend of actively using different kinds of platforms to consume content,” says Sarah Kim, SVP of Content Business and Regional GM for Asia at Viki. “Because of this, networks and production studios are able to try new and refreshing material beyond romantic comedies and family dramas, as well as explore multiple ways to introduce it not only in Korea but also outside of Korea.”

We’re also starting to see more K-dramas being renewed for multiple seasons, much like American TV shows. “We call this the Netflix effect,” says Jin. “Many Koreans suddenly started to watch American dramas on Netflix and learned the season system.” According to McKay, the motivation to extend a show’s life is primarily financial: “It’s more cost-effective to continue a storyline versus beginning production on an entirely new show.”

We can probably expect to see more of these changes in the future. But perhaps it is the impressive ability of Korean pop culture to adapt and be shaped by outside influences that has given it the widespread popularity it enjoys today. While there are many different factors that have contributed to the rise of Korean pop culture all over the world, a common thread that runs through all facets of the Korean Wave is South Korea’s openness to learning from other cultures, successfully combining elements of the East and West to create something new with mass appeal. Even if the characters in a K-drama are conversing in a language you don’t understand, the production itself is often compelling enough to coax you into overcoming the barrier of subtitles. It also doesn’t hurt that each episode ends with a cliffhanger, leaving you wanting more. Happy bingeing!