It was a Monday. I dropped ice cream on my kitchen floor and struggled for hours to clean up. By Tuesday, it felt like things were constantly slipping out of my hands. By Wednesday, typing had become difficult. I found myself making more and more unexplained errors in my emails and messages to friends and colleagues.

By Thursday, even the most simple tasks had grown unbearable. I woke up with an excruciating headache that felt like glass exploding in my head. As much as I dreaded how much a doctor’s visit would cost, I knew I couldn’t live like this. I printed out my insurance card, got dressed, and went to urgent care.

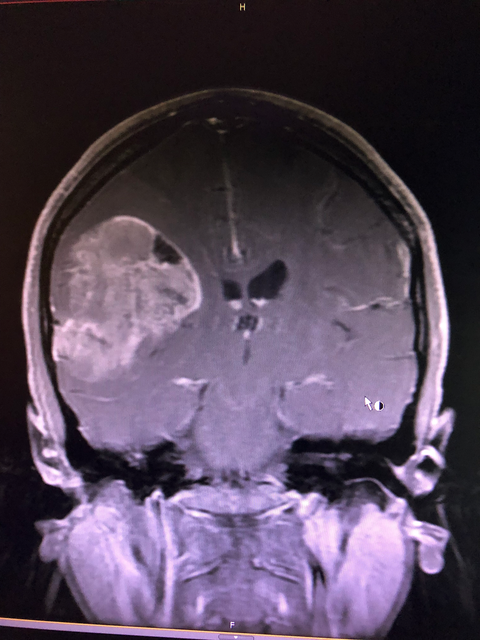

It took the doctor one look at my crooked smile and klutzy coordination to suspect that I was having a stroke. She urged me to immediately go to the ER. Two hours later, a CT scan revealed what was wrong.

I wasn’t having a stroke. I had a brain tumor—one that had grown to be 2.5” x 2” x 2.25”, about the size of a billiard ball. A biopsy would later confirm what the doctors already suspected: It was cancer—specifically glioblastoma, the most aggressive form of brain cancer that stole the lives of Beau Biden, John McCain, and Ted Kennedy.

Thinking about it now brings me right back to that moment of shock, horror, and disbelief. I remember my pleading questions to that emergency room doctor who delivered the news.

“Does this mean I’m going to die?”

“How long do I have left?”

“How is it treated? It… It is possible to treat, right?”

“Does insurance cover that?”

“I don’t know,” he admitted. “Insurance is evil.”

He wasn’t kidding. Since being diagnosed, treating cancer has often felt like a full-time job in itself, while paying for it has felt like another—both on top of the “real” job I must maintain to have health insurance and afford my copays, coinsurance, deductibles, and premiums in the first place.

How can we live like this? The answer is that we can’t—and in a sense, we don’t. From coronavirus to cancer, the people who can’t afford treatment (or even the testing to receive a diagnosis) are simply left to die. I’m one of the lucky ones who can afford to complain about it.

This is especially true for brain cancer, which has the highest average per-patient initial annual cost of care for any cancer group—almost $150,000. Even with insurance, I’ve already spent tens of thousands of dollars on emergency eight-hour brain surgery, six weeks of chemoradiation, and six more months of chemotherapy—all accompanied by necessary medication, weekly blood work, and bimonthly MRIs, the latter of which I will continue to need for the rest of my life.

Despite this premium pricing, treatment options for glioblastoma remain extremely limited. The FDA has only approved five medications (and one device) to treat brain tumors, and glioblastoma survival rates have barely budged in the last three decades. In the last 50 years, the United States has gone to the moon, cloned sheep, and synthesized meat. I refuse to believe that we can’t cure cancer, too.

In the last few months alone, we’ve mobilized for the development of a vaccine for COVID-19 at a previously unheard-of pace. The fastest vaccine developed before COVID-19 was for mumps in 1967—and that took four years.

It’s not just out of the goodness of their hearts that pharmaceutical companies committed to meeting an ambitious but necessary target: The Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Defense granted Novavax $1.6 billion and Pfizer $1.95 billion to develop, test, and manufacture this vaccine—in an initiative literally called “Operation Warp Speed.”

Drug companies invest in research for treatments that they know they can sell at an exorbitant profit. Right now, we are witnessing what’s possible when the size of the potential market is literally every person on the planet.

The for-profit nature of what gets researched and what doesn’t in our country isn’t the best setup for public health, and universal medicine is the clear long-term solution. But our federal government is also right to use the tools already at its disposal to incentivize innovation. Its investment in finding a coronavirus vaccine is exactly the kind of scale, commitment, and fervor we need to fight a global pandemic.

But what about more “niche” diseases like glioblastoma—or the broader category of cancer, which isn’t niche at all?

Nearly two million new cancer cases are expected to be diagnosed before this year is over—and 606,520 people are projected to die from the disease in the same span of time. That’s an annual figure, for just the United States. One in six people worldwide will develop cancer in their lifetimes, with a proportionate number of deaths (about 9.5 million) attributable to the disease. In the past year alone, we’ve lost too many extraordinary figures to cancer, including Little Richard, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, John Lewis, Chadwick Boseman, and Alex Trebek.

If the current trends continue, global cancer incidence is projected to increase by 62 percent by 2040—and deaths attributable to it by 72 percent. There is clearly a growing global market for a cure.

In the United States, cancer death rates are declining overall, but that’s driven by breakthrough treatments for skin and lung cancer. For colorectal, breast, and prostate cancers, progress has slowed—and for glioblastoma, the progress has never been worth writing home about. Brain cancer, and especially glioblastoma, remains one of the deadliest cancers—and even after decades of underfunded research, we don’t even have a college semester of added life expectancy to show for it. Most countries are still facing an increase in the absolute number of new cancer cases being diagnosed each year.

That’s why we need aggressive federal leadership to mobilize for other diseases, especially cancer—and concrete mechanisms for accountability to see that initiative through.

If not now, when? Doctors still don’t know what causes brain cancer. Look at me: I don’t smoke. I wear sunscreen, eat a healthy diet, and exercise. I don’t have any underlying health conditions. My family, like most, has some history of cancer at old age, but no history of brain cancer—and none as young adults. No one could have predicted my glioblastoma diagnosis—and especially with the extremely limited understanding of this disease that we have today, it could still just as easily happen without warning to someone reading this.

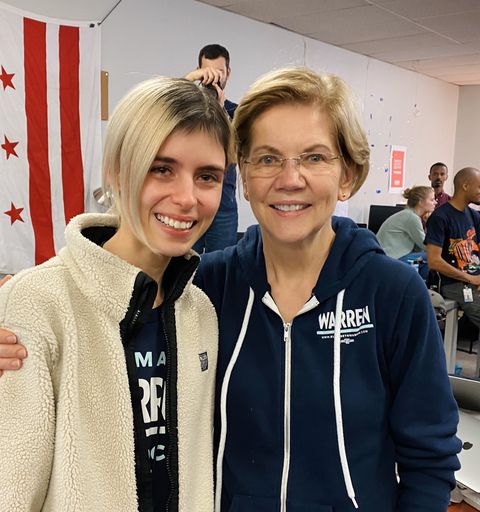

Though I’ve been so proud and grateful to have served in my dream role as social media director for Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign, I’m thrilled that our new president is a tireless champion for cancer patients and survivors like myself. Both long before and now well after learning my diagnosis, I’ve been vocal in my praise of Joe Biden’s exceptional leadership on fighting cancer in the memory of his late son, Beau. Kamala Harris’s life has also been touched by cancer—her mom lost a battle with colon cancer, leaving behind a powerful legacy of significant contributions to the fight against breast cancer. Now, their leadership also carries deeply personal meaning and impact for me.

In his final January 2016 State of the Union address, then-President Barack Obama appointed then-Vice President Biden to lead the White House Cancer Moonshot, an unprecedented national effort to end cancer by making “a decade’s worth of advances in cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment in five years.”

It was a fantastic start. I commend President Biden for continuing this effort past January 2017 through the Biden Cancer Initiative, an independent nonprofit organization. But he resigned just two years in to focus on his presidential campaign—and in July 2019, less than a month after my own diagnosis, the organization suspended operations entirely.

I’m optimistic that this was for the best. No one is better positioned, knowledgeable, or passionate to mobilize the kind of aggressive federal leadership we need to cure cancer than Joe Biden—and no title is better equipped to make it happen than President of the United States.

Biden knows we can’t just count on Big Pharma to pursue treatments and cures out of the pure goodness of their hearts, or to set the budgets and draft the legislation to make it happen. He knows we need investment with accountability, paired with unprecedented ambition and commitment.

To hit the ground running, he should start acting now to assemble the team and framework for a new initiative to cure cancer—one with bigger vision, bigger ambition, and a much bigger budget. In 2021, we can finally defeat COVID-19—and then channel that same intensity into curing cancer. In Joe Biden, we have just the president to do both.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io