Last weekend, my family of four—my husband, 5-year-old son, 22-month-old daughter, and I—went to the zoo. We played on the playground, saw the giraffes and lions, and ate a picnic lunch.

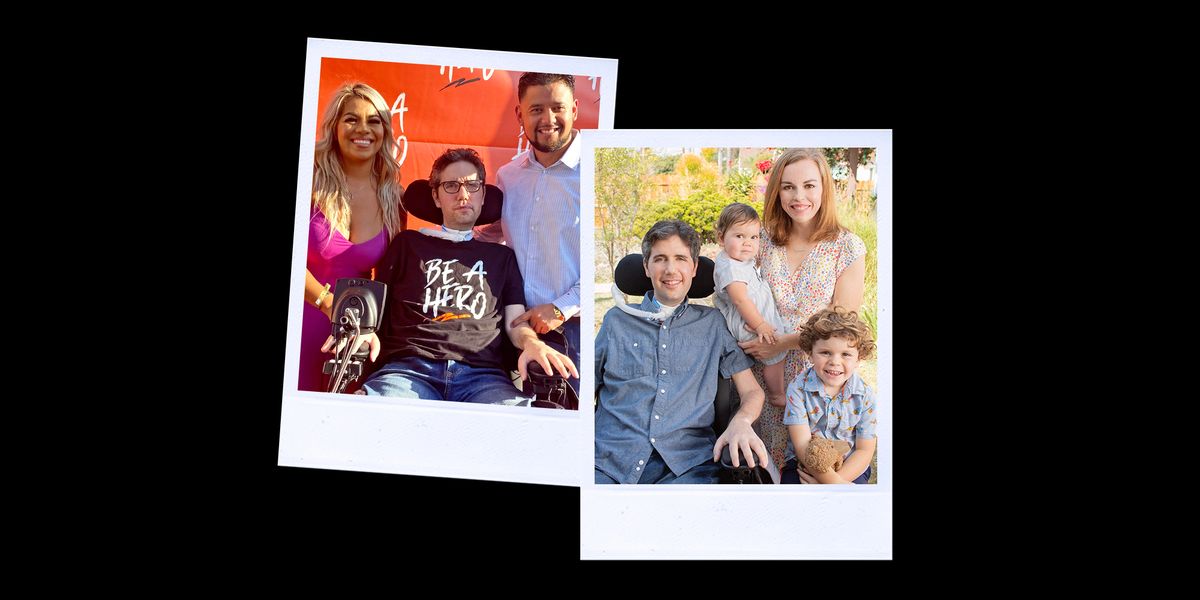

This may not sound remarkable, but for us, any outing is an expedition. My husband, healthcare activist Ady Barkan, has had the neurodegenerative disorder ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, for nearly five years. He is almost completely paralyzed and uses a wheelchair to move and a computer tablet that tracks his pupils to communicate.

That zoo trip was only possible because of a fifth person who was with us: Rosalba, a member of Ady’s team of caregivers. At least one caregiver is with Ady 24 hours a day, helping him get in and out of bed, dress, shower, eat, and work, among many other activities. Alone, I would not have been able to drive Ady’s wheelchair, supervise my son, and pull my daughter in our red wagon, but with Rosalba at the zoo with us, we were able to have a fun day out as a family.

In recent months, care has moved from being a personal concern to a political flashpoint. Democrats and Republicans have argued over the meaning of “infrastructure,” debating whether that term should include caregiving and education. Republicans want to confine federal spending to “hard infrastructure” like roads and bridges and accuse Democrats of “redefining” infrastructure to also cover childcare and in-home health care.

The Republicans got their way in the Senate’s bipartisan $1 trillion infrastructure bill, which passed in August without President Biden’s proposed $400 billion in care funding. Now, the fight has turned to the Democrats’ $3.5 trillion budget, which they hope to push through Congress via the reconciliation process. The budget package has no Republican support and Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, as well as moderates in the House, have said they think the price tag is too high. Congressional leaders are hashing out how much to request for care spending, with the House Energy and Commerce panel putting forward just $190 million—not enough to clear current waiting lists for home care or provide a living wage to caregivers.

Meanwhile, progressive House Democrats have said they will only support the bipartisan infrastructure plan with sufficient funding for care in the budget package. If Congress cannot agree on a budget resolution by midnight tonight, the government will shut down.

Republicans’ cynical argument that care does not count as infrastructure is easy to rebut. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its school and daycare closures driving many parents out of the workforce, has shown the extent to which our society relies on caregiving support—and how disproportionately this burden has fallen on women, especially women of color. The recent failure of care systems crystallizes how care provides the basis for the economy to function.

My life depends on caregiving support. Without Ady’s caregivers, I would barely be able to leave the house, let alone have a demanding career as an English professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The same goes for childcare, where we have a support network of wonderful daycare and elementary school teachers.

As both a caregiver for Ady and our young children and a specialist on 18th century literature and media, I have a unique perspective on these interconnected issues. History demonstrates that the care economy is nothing new, and that “infrastructure” is just a comprehensive word for the kinds of intangible supports that have enabled major advances in the past. Large-scale social improvements have always relied as much on educational and social networks as on physical developments in transportation and communication.

Enlightenment Britain was known for its infrastructural improvements. New turnpikes and improved road surfaces cut travel time between many locations by as much as half, speeding up the mail and allowing news to circulate more quickly. Advances in drainage and the expansion of canals contributed to the Agricultural Revolution, cutting hunger and increasing birth rates. The spread of oil street lights and the introduction, in the early 19th century, of gas lamps made cities safer at night, while the covering of open sewers made them both more fragrant and more sanitary.

But the advances of the Enlightenment—which we still associate with modern values of reason, equality, and human rights, despite the fact that it was also the era of chattel slavery and consolidating colonialism—depended as much on human infrastructure as on these material changes. Academies, debating clubs, and civic improvement societies spread new theories of the Scientific Revolution and urban planning. Salons and correspondence networks circulated literary and philosophical works. Commentators understood these changes as interlinked: material, intellectual, social, and personal improvement were mutually reinforcing. As Enlightenment philosopher Dugald Stewart wrote in 1792, “all the different improvements in arts, in commerce, and in the sciences, [were] co-operating to promote the union, the happiness, and the virtue of mankind” and paving the way for “a more enlightened age.”

Although there was an expansion in schooling, most childcare and healthcare still took place in the home. Parents in the past often expressed their emotions about the difficulties of what we now call parenting, sleep deprivation, and burnout. But they came up with solutions that spread caregiving duties over multigenerational family and friends, rather than seeing it as the responsibility of each individual nuclear family.

The close-knit Shackleton family of Ballitore, Ireland, offers a case in point. Across several generations, members of the family—three of whom were headmasters of the Ballitore School—discussed childbirth, early care, and education, as well as healthcare issues for many members of their community. Sarah Shackleton frequently traveled from Ballitore to her sister Margaret Grubb’s home in Clonmel, about 70 miles away, to assist Margaret during childbirth and the newborn phase. (Margaret had a total of nine children.) In 1786, following the birth of her fourth child, Margaret wrote to their father, Richard Shackleton, that Sarah’s “company … was a great consolation & support to me,” adding that “when the trying time [of childbirth] arrived she aided then, & so tended & reared me after, that I recovered surprisingly.” Sarah, however, disclaimed praise for her help, writing, “Thou pains me by saying anything of being obliged to me, I frequently at the time, & since, thought I did very little to assist thee in thy family.”

Sarah and Margaret also cared for a third sister, Deborah Chandlee. When Deborah was facing financial hardship after her husband fell ill, the family came together to support her, with Sarah, Margaret, and their brother Abraham each contributing £10 a year so that she would not have to “go to service,” that is, become a paid servant caring for others. Margaret also took in two of Deborah’s daughters.

In her new book Communities of Care: The Social Ethics of Victorian Fiction, Talia Schaffer details how standard such care arrangements were. She describes the “forms of communal care that constituted ordinary life,” adding that “the nuclear family is an exception—a short twentieth-century blip—in the long-term, robust tradition of collective social life.” In an era before modern medicine and most social welfare systems, such arrangements were necessary for survival.

Of course, the communal nature of caregiving did not mean that it was easy. It tended to fall on women and was often extremely draining, especially with large families and high rates of infant and childhood mortality. In 1770, Margaret Grubb, writing a letter while her baby slept, worried that “the best of my days, the bloom & prime [were] passing away”—a sentiment that may feel familiar to many parents of small children. But by understanding care as crucial infrastructure, we can start to recapture some benefits of a more collective view of childcare and homecare.

Right now, our society treats such needs as an individual problem. Parents of young children struggle to find high-quality, affordable daycare and preschool, as only four states and the District of Columbia spend enough to provide universal, high quality, full-day pre-K programs, and six states provide no state funding for pre-K at all, according to the National Institute for Early Education Research. As we have seen in the past 17 months, our society cannot fully function without childcare. Understanding homecare and childcare as a form of infrastructure—the “subordinate parts of an undertaking,” “substructure,” or “foundation,” as the Oxford English Dictionary defines the term—illuminates our collective need for caregiving support, whether for children, disabled people, sick people, or older Americans.

Today, families are smaller than in the 18th century and people often live thousands of miles from relatives. While many people continue to participate in the kinds of informal care arrangements the Shackletons practiced, we need reliable systems in place to allow women and men to pursue careers, raise families, and live full lives. We now have an opportunity to remake our society with caregiving at its core. History shows us that, in doing so, we would not be “redefining infrastructure”; rather, we would be affirming the structures that have always allowed us to survive and thrive.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io