Michael Smith once picked a fight with Barack Obama. Smith, the First Family’s interior designer, argued that red curtains were the perfect choice for the Oval Office. Obama disagreed. Presidents, of late, had gone with yellow or blue. Smith dug in, and others chimed in. Was this about fabric, or something else?

“Barn red,” Smith called his curtains. Suddenly, they sounded pastoral—no echoes of Belle Watling or Buckingham Palace. Then, flanking the curtains, the designer added two sunny paintings of Cape Cod barns by Edward Hopper, a favorite of the president’s. They belonged on the walls, at the dawn of the Obama administration, because of their Americana calmness and playful shapes.

Smith often connects to people through places. For example, he is from Pasadena, and the president is from Honolulu. The two men are roughly the same age. The president likes golf, and the designer likes country clubs. They have a Pacific view that America was strengthened as much by its frontier mentality as its Establishment ethos. “When you grow up in California, you are basically suspicious of anything that seems formal or representational,” says Smith, noting that the president, though thoroughly Ivy League, spent his first two years of college at Occidental in L.A. “Rooms that are meant to impress, to be patriotic, to be heroic—you’re suspicious of them,” Smith adds.

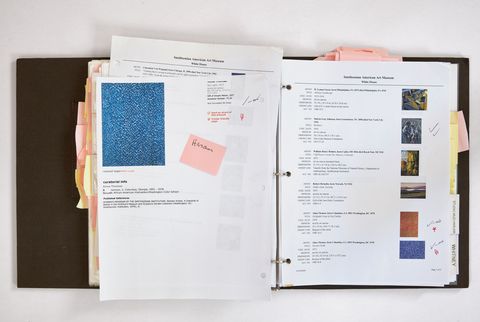

“There are few instances when they are used for good.” President Obama and Smith developed a joshing rapport, like the hot and cold personalities in a buddy movie. Smith began to appreciate the president’s bent for modernism, and the president was awed by the White House’s neoclassical architecture, once he started living within its walls. With the First Lady leading their joint conversations and explaining their decisions to the public, the three brought together different and distinctly American ways of seeing the world, all under one roof. Smith’s new book reveals the White House’s private spaces, and reminds aficionados and everyday Americans that Smith and the Obamas were really onto something. The artwork they borrowed, mostly from federal museums, showed how diverse artists and styles and eras could hang together—and redefined who belonged in the White House.

In 2009, when the Obamas announced their list of loaned artworks, the name that drew gasps was Glenn Ligon’s. The contemporary-art agitator, who is African American and gay, repeated a stenciled sentence that gets denser and darker in his work Black Like Me #2: “All traces of the John Griffin I had been were wiped from existence.” Ligon is sampling John Howard Griffin, the white journalist and author who changed his skin pigment, elaborately, so he could pass as African American. The art world was electrified—the Obamas had jumped into a roiling debate and declared that the time had come for new images, new visionaries, new juxtapositions.

“It’s not about the specific artists, but the broad strokes of the spaces,” Smith says now, years after the Obamas returned the art. He is proud, for example, of paintings by George Catlin, featuring colorful Native Americans riding at full gallop, not just for their historical value but because Mrs. Obama put them in the Treaty Room, across from an equine painting by Susan Rothenberg with a rose-colored background. It’s as if all the pretty horses, from the last century and the one before, got corralled together.

The Obamas chose quieter and no-less-bold work to hang near a Monet outside their master bedroom: a bright blue canvas called Sky Light. Color-field artist Alma Thomas had arranged these big dabs of paint in loose columns, in her kitchen studio only a short distance from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, in the years after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. After elevating the first-ever African American female artist to be featured in the White House collection, the Obamas wanted to do even more.

Next, they gave Smith the Old Family Dining Room to reconsider—a flex-space, spillover room that was often home to catering carts. The First Couple refreshed the decor with a Machine Age tea service, a monumental Rauschenberg, two Josef Albers paintings, and a rug adapted from a weaving by Anni Albers.

“This is artwork that should stop you in your tracks for a moment,” explains Adam Weinberg, who runs the Whitney Museum, which loaned the Hopper barns to the Obamas. All the grace notes “are channeling the Obamas’ idea of hope, by not just looking back at the past but also embracing the present.” Suddenly, the room had new purpose, for walking tours and friends and staff Seder meals, and the first thing anyone saw was another stunner by Thomas—her rainbow-hued Resurrection, a bright eye watching over a room once dismissed as unworthy.

Smith’s book lingers on one Norman Rockwell painting that hung for a while in the West Wing. It has one of the most racist epithets for a Black person scrawled on a wall above a little Black girl walking to school. The president invited Ruby Bridges, the school-integration pioneer–turned–activist, to come see it. She is the grown-up who was once the girl on her way to school in New Orleans, and the art became a mirror.

When the president chose barn red curtains, he also opened the symbolic barn doors to present “not himself as a person but America as a people,” as Smith puts it. Those Hopper barns, Weinberg says, are not only contemplative, and sort of modernist; they were also painted by a staunch Yankee Republican who rarely interrupted his summer idyll in Truro, except once: to make sure he could vote against Franklin Roosevelt.

President Obama often tried to win over those who voted against him. Mrs. Obama similarly let everyone know that the White House was open to all, especially anyone who assumed that they were not welcome. Inside their home at the White House, through the First Family’s taste and tact, Americans were able to see—finally and completely—a house full of paintings that reflected who we all are. Black artists next to white peers, women expressing themselves with the same force as men, someone gone and unsung celebrated with someone just breaking through.

And that painful, pretty Rockwell, entitled The Problem We All Live With.

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io