Undercover Underage, a new docuseries from discovery+, follows 38-year-old mom of three Roo Powell as she dons disguises to take down dangerous predators. With help from her team at SOSA (Safe from Online Sex Abuse), Powell uses wigs, colored contacts, and fake braces to physically transform into a 15-year-old girl and catch online predators looking to groom young girls. Once an adult makes contact with her “decoy” character, SOSA’s crew of investigators work tirelessly to gather bits of information about the perpetrator—complicated work that is often extremely dangerous. If and when a crime is committed, SOSA turns over their findings to law enforcement.

Now available to stream, Undercover Underage features several real-life stings led by Powell. Below, in her own words, the child activist—and amateur actor—on why she’s dedicated her life to preventing the exploitation of teens online.

Flori is 15 years old. She is half white, half Filipina, with braces and wavy brown hair. She lives with her mom, who works late nights at a hospital. Her dad hasn’t been in the picture since he moved out of state with his new family.

She grew up Catholic, likes to go on runs, and occasionally plays the piano. Her blue-walled room is decorated with a tapestry depicting the moon phases. Twinkly lights hang from the ceiling. Notebooks and homework clutter her writing desk, and pages ripped from magazines are taped to the wall. She posts videos to TikTok and selfies to Instagram.

By all appearances, Flori is a typical teenager. Only she doesn’t really exist. I am Flori—or rather, I embody Flori to catch online predators.

Technology is a wonderful thing. But it’s also an avenue for child predators. In 2020, I formed the nonprofit Safe From Online Sex Abuse (SOSA). We work to reduce the amount of online exploitation by identifying dangerous pockets of the Internet, speaking at schools, and encouraging state legislators to raise the age of consent. We also help law enforcement track down offenders by using fictitious underage characters like Flori. We call them “decoys.”

One question I get a lot is whether I am somehow exploiting these perpetrators. We let the predators drive the conversation by taking a hands-off approach. We tell them at the outset that we are underage. We also do a lot of reminders, like “I’m coming home from school,” or “I just did my algebra homework,” or “I wish I was old enough to drive.” We offer off-ramps, too, telling them, “We don’t have to meet if you don’t want to,” or “Are you sure you want to be talking to me and not someone your own age?”

What we do is really different from Chris Hansen’s To Catch a Predator. This isn’t some game of gotcha. When I am Flori or any of the other decoys, my goal is to identify perpetrators illegally interacting with underage kids. If I can do that successfully, the information goes right to law enforcement, who can either do an independent investigation, take over my accounts and communicate as our decoy, or partner with us to catch the predator.

We have a rolling staff at SOSA to help make our characters more realistic. Matt takes and edits pictures that we send to the people who contact us. Shelby has unique knowledge of niche parts of the Internet, and does a lot of our work on social media. Avalon helps build the decoys to make them believable, like determining Flori’s astrological sign, where was she born, and what her favorite hobbies are.

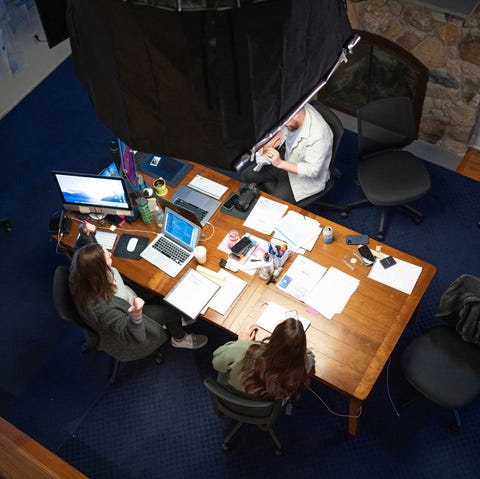

We all work from a big rental house with four bedrooms decorated to match each decoy’s personality. We set-dress two bathrooms, and use the kitchen as needed. Wigs, colored contacts, fake braces, and clothes are stored in a closet. The living room acts as our “situation” room, where we do research and plan “sprints,” as we call them, to identify perpetrators.

At SOSA, we’re interested in detecting patterns around how predators target children. What we’ve found is that they tend to start by asking about parental oversight. We’ll be communicating with an ACM (or an “adult contacting a minor”) and right away they say, “Tell me about your dad.”

I’m Asian-American, and some of our decoys are Asian, so it’s been really interesting to see how the fetishization and dehumanization of Asian girls plays into online predation—so does socioeconomic status. If a girl is looking for money, there are adults who will say, “I’ll send you $200 if you text me X, Y, Z, or if you get on a video chat.” It’s not hard to see how attractive that offer is to someone in financial need.

One time, we had an abusive perpetrator block us after reaching out to one of our decoys on Reddit for material for his own self gratification. I was so irritated we didn’t find out who he was was before losing communication, because this was clearly not his first rodeo.

About a month later, we checked the DMs of a different decoy and he just so happened to reach out. We were like, holy shit. First of all, what are the odds? Second of all, how often does he do this? And third of all, we now have another opportunity to find out his identity. He’d already seen me as one decoy, so we threw together a very quick new persona with glasses, blonde hair, and red lipstick. Through that second decoy, we were able to identify him and send his information to law enforcement.

The conversations I have with predators can take a toll, especially the ones over video. One guy was very clear about his intentions and really aggressive. I had to pretend like I was enjoying what he was doing while video chatting. He kept asking me to remove by blouse, so in order to placate him I spun the phone camera around so he could see my legs.

There are other times when a perpetrator will do something really heinous, but it’s not quite breaking the law. In some states, it’s not illegal to message an 11-year-old and ask for photos of her feet so you can gratify yourself. It’s creepy, it’s wrong, it’s abusive—but it’s not illegal. Many of these perpetrators know what the law is, so they dance around it. It doesn’t have to be illegal to be abusive, so there’s nothing you can do. Law enforcement can’t pursue it because no law has actually been broken.

I compartmentalize what I do by keeping my professional and personal lives separate. I don’t have pictures of my kids on my desk, because I don’t want to see their faces while I’m doing this kind of work. I use a different phone to text with perpetrators, because I don’t want to get a dick pic on the same phone I’m using to take pictures of my child’s sporting event. Dick pics are ten-a-penny for me. At this point, the number of dick pics I’ve seen is in the four digits. If there was a such a thing as eye bleach, I would invest.

I have a therapist. I keep a weighted blanket on set. I do yoga and meditate. At night, I turn on Planet Earth on mute and listen to violin sonatas. If I have to work late, I don’t go home. I stay at the house and crash on one of the decoy’s beds.

One of the hardest parts about this job is not knowing what happens after we report someone to law enforcement. Sometimes we don’t know what happens with a case, or we find out about an arrest because we see it in the newspaper. It makes it hard to quantify how many predators we’ve helped catch, but I have passed along hundreds of cases. What keeps me going is knowing this is happening to me and not a real child.

What we do isn’t the end, it’s the means. We all need to come together to find paths to rehabilitation for would-be perpetrators, change legislation to raise the age of consent, introduce empathy-led education in schools, and help parents support their kids.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.