The women of Suffs had a plan. Much like the characters in their buzzy musical—which traces the fight for women’s suffrage from 1913 to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920—creator Shaina Taub and her team had considered the perfect time to make their case to the country: In Sept. 2020, the show would premiere, falling right after the centennial of the 19th Amendment and right before the litmus test that was the presidential election.

But like the path to suffrage, there were still a few twists to come. The pandemic ended up shutting down productions across the country, and Suffs wouldn’t open at the Public Theater in New York City until March 2022. With President Biden in office and the Supreme Court poised to overturn abortion rights, Suffs entered at an even more complex, and perhaps even more fitting, moment in time.

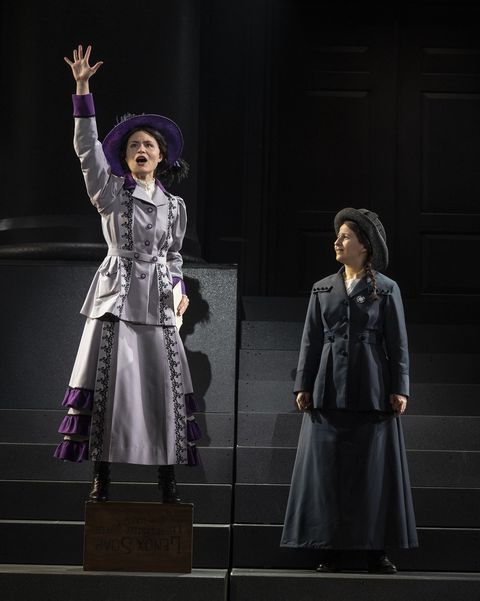

Taub, who wrote the book, music, and lyrics, stars in the show as Alice Paul, the radical suffragist and leader of the National Woman’s Party, who’s determined to secure the right to vote at all costs, even if it means sidelining her fellow women of color. She clashes with the older Carrie Chapman Catt (Jenn Colella), the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, whose strategies Paul finds slow and insufficient. (Paul, on the other hand, is bold in her approach and eventually gets thrown in jail, where she and her cohort are force fed after going on a hunger strike.) Their relationship is mirrored by prominent Black journalist Ida B. Wells (Nikki M. James) and activist Mary Church Terrell (Cassondra James), who have friendly disagreements about how to work with the white suffragists. By the end of the show, Paul finds that, having lived to see the rise of second wave feminism, she’s now become the old guard—the new beginning of a necessary cycle. All the characters, including the men, are played by women and non-binary actors, with women of color often, and purposefully, portraying historically white figures.

Naturally, it’s drawn comparisons to Hamilton, another historical retelling that first premiered at the Public. Suffs even features one of the leading women from Hamilton’s original Broadway cast, Phillipa Soo as the dazzling suffragist and labor lawyer Inez Milholland. Though the musicals have distinct differences (more on that below), Suffs seems to have taken on some of the same fervor; with performances consistently sold out, Bloomberg reported resale sites were listing Suffs tickets for thousands of dollars. And in the same way Hamilton fit perfectly within the hope-filled Obama era, Suffs seems to reflect the current national mood, reminding us that “the work is never over,” “keep marching.”

Taub and I were first set to talk on May 3, the day after Politico reported that, per a leaked draft opinion, the Supreme Court would soon vote to overturn Roe v. Wade. We rescheduled the interview, and Taub and her castmates headed to Foley Square in Manhattan to perform at an abortion rights rally. As news of the leak settled, and I considered the long road ahead for reproductive justice activists, I thought of one of Suffs’ early moments, when Paul and her right-hand Lucy Burns (Ally Bonino) consider how they’ll plan the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession, the first large-scale political march on Washington. Alone in an office, the two sing to each other: “How will we do it when it’s never been done? How will we find a way where there isn’t one?”

For now, it’s a question audiences will have to take with them, as Suffs will have its final performance at the Public on May 29. But Taub has hopes for its future. “I’d love for it go to Broadway,” she told ELLE.com. “I just feel it in my bones that we’re not done. That’s our dream, for sure.” Below, she shares more about how Suffs first came to be, what it’s been like to have activists like Gloria Steinem stop by to see the show, and why it’s important to her to use Suffs’ newfound platform to contribute to these ongoing fights.

What first made you think that the story of women’s suffrage should be a musical?

Rachel Sussman, one of our producers, gave me the book that suffragist Doris Stevens wrote called Jailed for Freedom. I couldn’t believe it hadn’t made it to me yet. Besides the fact that it’s an untold, crucial chapter of our history, it was so dramatic and dynamic. These protests the suffragists pioneered were really the first examples in American social movements of this massive, visual rhetoric, of literal choreography and music and pageantry and color and formation and parades, picket lines. Just the staging of the protests alone was so inherently theatrical to me. Then the more I went down the rabbit hole of each individual woman who was involved, I was like, “These are such complicated, interesting, unusual, extraordinary, flawed, specific people who seem ripe for dramatization.” It just fired on all cylinders. I kept looking over my shoulder being like, “Someone else must be writing about this.” There should be 100 suffrage musicals. There are so many more stories than my one two-and-a-half-hour show could possibly contain.

You’ve previously mentioned the show changed a bit after the racial reckoning of 2020. How did Suffs evolve during that time?

It’s always been my intention with the show, from its earliest inception, to be really honest and unflinching about the racism that existed in the movement. Right before the pandemic was when the first real, full draft of the show existed, and we were about to do a couple more developmental steps that got cut short because of the shutdown. In that year and a half before we ever got back into a room, me and my collaborators realized, we have an opportunity here to, not only deepen the script in how we are portraying the characters of color and their arcs in the show, but also how are we casting the show? How are we being honest about the racism within the history and creating a production that represents the values we have as theater makers?

We brought on the brilliant scholar Ayanna Thompson, who is so incredible with so many things, but she’s specifically a casting scholar. She really challenged us to rethink our casting practice. What does it mean to have women of color on stage portraying both women of color and white characters? How could we create a language onstage that could help an audience understand that complexity? It was getting specific and intentional about every single role and the holistic building of the ensemble.

Then even offstage, figuring out, how are we going to make our processes more inclusive, safer? How do we create more time and space for dialogue, for compassion in the room? I chose to write a show about very fraught topics of race and gender and sexuality and history in our country, and that requires care. Our hope was to create an environment where people felt empowered to feel like a real collaborator in the room.

After all the delays, how does it feel to have the show being performed now, during this political moment?

In the initial years, when it was just me and Rachel, we had these dreams of, we’ll do the show, and President Hillary Clinton will come see it. Of course, that didn’t come to pass. There was a new tone of darkness and dread that overtook all of us. We thought [we’d premiere] in fall 2020 and that the specter of the 2020 election hanging over us would be a part of that. Then that didn’t happen. And here we are now, in this third American moment where it’s not the optimism of late Obama years coming into what we thought was the first female president. It’s not the existential dread and horror of 45. It’s somewhere in between, where all those forces of oppression are very alive, gaining power. Our country’s so divided. Women are getting legislated out of existence, and yet we, ideally, have a progressive champion in the White House, even though he maybe is more moderate than we would like. And we have the super strong progressive movements on the ground fighting.

It’s a thornier moment, and I think it all sort of happened how it’s supposed to be, because the show is about that thorniness, [about how] social movements are not black and white. It’s not the good guys versus the terrible tyrant, and we eventually prevail and get the change done, boom, the end. That’s not how it works. Part of the provocation of the show is you need a multiplicity of tactics to achieve change. You need the Alice Pauls burning the president outside while Carrie Catt is inside having tea with him. Conflict within a movement is actually healthy and helpful.

How did you decide to make those intergenerational conflicts such a prominent part of the show?

I knew I didn’t want to make the central conflict just between suffragists of all stripes and the forces against them, because I didn’t want this to just be this simple, we were on the right side of history [story]. To me, it was more interesting to stay within the movement. And it was this quote I saw early on that Susan B. Anthony said, something like, “There never was a young woman yet who didn’t think, if only she had had management of the work from the start, the cause would’ve been carried long ago. I felt just so when I was young.” If you stay in the movement long enough, you become that old guard who’s doing everything too slow and wrong, and the young are telling you all the reasons you’re doing it wrong.

For me, it resonated, not only in the themes of social movements. I can only speak for my own experience, but as a woman coming up in theater, it’s like, you’re young, and you’re out of college, and you’re like, the way they do things in this business is backwards, and we’re going to blow it all up and take over. Then we all have those moments where we’re kind of like, oh my god, am I the old one now? Movements or no movements, I wanted to dramatize that feeling you have when you’re like, oh my god, I’m becoming my mother. I hadn’t ever quite seen that dramatized, that experience as a woman of what it feels like to be encountered by your younger self and the complicated feeling of that. It’s not all warm and fuzzy.

The show has been getting a lot of Hamilton comparisons. How has that felt?

Hamilton is the most successful musical of all time, so even to be mentioned in the same sentence as it is exciting. I love [Hamilton creator] Lin[-Manuel Miranda], and all the people who made that show have been so incredibly supportive. Of course, the superficial similarities are obvious. I wrote it, and I’m starring in it. It’s in the literal same theater. It’s about American history. And also, I challenge the comparison, because it is so fundamentally different. Hamilton told the story of a lot of people we know really well already, who did have that power and agency to create our Constitution. And that power wasn’t really questioned.

With Suffs, I’m dealing with women the majority of my audience have never met. So this is an entry point. It’s the story of Americans who were intentionally, by design, kept out of the systems of power and how they refused to accept that and pushed against it. And moreover, there’s not a stylistic mashup. With Hamilton, there’s the brilliance of, here’s this founding myth we all know, and here it is told through hip-hop. With [Suffs], there’s no existing thesis. There’s no script to flip. So I didn’t go the route of a pop rock, contemporary score. It’s a story of social movements and the messiness of how they get made, and I can’t really think of another musical that does that. Maybe Newsies. And I love Newsies! I saw the movie as a kid and was like, “I want to do Newsies with girls.” I feel like that’s exactly what I did.

There’s also been this activism arm to the show. Hillary Clinton and Lin-Manuel Miranda participated in a Suffs event benefitting political action organizations; the cast went to a rally for abortion rights. Why is that aspect important to you?

Music, theater, storytelling, art has a huge role to play in the movement, because we’re able to humanize these issues. Changing the Constitution felt completely insurmountable when [the suffragists] started with just two girls in the basement office, and yet, they did it. They also messed up in a lot of terrible ways, but both are true. And if they can do it, we can do it too.

It’s also always been my hope that we, as a cast and as a production, can use whatever platform we have and identity we form as Suffs to lend ourselves to these fights. I’m lucky to be involved with a lot of organizers within these progressive movements. After that SCOTUS ruling leaked, it was going around that there was this rally, and Donna Lieberman, who runs the NYCLU, was like, “Would Suffs want to do something?” I sent out the email to our cast that morning, and immediately, people wanted to come. So much of organizing and mobilization is to not wait for an emergency. It’s to be ready. All it took was one email to have 15 incredible artists already know the song that was appropriate for the moment to sing for the cause. And that’s always been one of my goals; we are like emergency responder artists, ready to roll. I hope that can happen again and again.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Activists have also come to see the show, people like Gloria Steinem and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. What have their reactions been like?

I was really honored that they seemed to express that it resonated with the things they have dealt with. I’ve seen it play out among AOC and all these young new legislators who are like, Green New Deal now, health care for all now, and you see an older generation [in] Nancy Pelosi being like, “Well, we have to do…” That real divide feels alive in how it behooves the systems of power to make us think that the narrative is about them versus each other, when really, I believe they’re fighting for the same thing but just have different tactics. And like I said before, I think you need the Alices and Carries. You need the AOCs and the Pelosis. So to actually get to sit and chat with them about that was very meaningful. Also Alice Paul lived through 1977, and I’d been dying to ask Gloria Steinem if they had ever encountered each other. She said they hadn’t, because in Alice’s later life she was in a nursing home, and they hadn’t crossed paths. But it’s crazy. You can reach back and touch this history.

What do you hope for the future of the show?

We all have big dreams for it. We’d love to do it again here in New York, and my hope is to one day take it around the country, and even beyond that, for schools and communities to be able to put it on themselves. But I don’t feel even 100 percent finished with the writing. Being in the show every night, there’s so much I’ve learned, and I’m so excited to keep working on it. We have incredible producers and this incredible momentum, and I feel hopeful that we’ll get to have a future to do that. So I mean, I’m not going anywhere.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io