As a single person living through the pandemic, let’s just say it’s been a long time since I’ve touched another living being other than my dog. I’m not at all happy about this state of affairs, but I have found one balm for physical contact, one source of who-cares-about-the-news mind-numbing pleasure. A book version of Xanax: romance novels.

I’m late to the game. My first interaction with a romance novel didn’t go very well. I was a sophomore in high school and my friend’s roommate gave me a well-worn copy of a bodice ripper about two Regency era aristocrats falling in love with a Fabio lookalike on the cover. Women were ravished and the sex involved a lot of euphemisms. This was the ‘90s, and my preferred source of hunks or sexual tension was 90210 or Basic Instinct. I dismissed the whole romance genre as not for me.

Fast forward a couple decades, and I read Jasmine Guillory’s The Wedding Date two years ago when I needed a Trump-era respite from the world. It is about two people who meet cute—pretending to be together at a wedding—and end up falling in love. It was like a rom-com, but with more sex. Really good sex that was about consent and feeling comfortable in one’s body but also featured mind-blowing orgasms. And a lot of great meals. The Wedding Date is the first of a series of now five books in a shared universe. I immediately read the second, The Proposal. I could not devour them fast enough—I was hooked.

I know I’m not the only one. Bridgerton, the smash-hit Netflix series, got its start as a romance novel. Today’s romance titles go way beyond Regency-era aristocrats and are written by and about women of color, trans and nonbinary authors, people with autism, and people who aren’t rich. Here we are in post-Fifty Shades, post-#MeToo, post-2016 election America, mid-pandemic—none of which feels all that romantic. And yet we’re experiencing a boom in the genre: in sales, in books being optioned for TV and film, in bookstore real estate, and in media interest.

Guillory’s heroines are often Black women who routinely navigate topics like race, body acceptance, single motherhood, and professional advancement without feeling like Very Special Episodes. Until recently, Guillory worked as a lawyer, and has experienced the kind of crossover success that makes converts of non-romance readers like me. Her novels make The New York Times Bestsellers list and are chosen as Reese Witherspoon book club picks, and I cannot wait for someone to turn them into a TV series. (A message to Shonda Rhimes: You are responsible for Bridgerton, please, please consider turning the Guillory books into a series. They are made for you.)

Part of the genre’s success in attracting new readers is that the books are starting to be branded like the romantic comedy movies we so rarely get anymore. “The marketing for romance has gotten better at finding people like you, who didn’t think romance was for them,” Guillory says. Her books all have cute illustrations on the cover, not shirtless men and scantily clad women, so they blend well with the other books on my coffee table and I don’t feel like I need to hide them. I realize that sounds vain, shallow, and not at all adventurous, but those are the kinds of barriers to entry that genre books face.

Major publishers have also started giving romance authors not just deals, but a significant amount of promotion for books whose protagonists (and often authors) come from marginalized communities. “Those writers were always out there—maybe publishing with small presses or self-publishing—but often publishers had the attitude of, ‘We already have one Black author.’ Now they’re finding those books can sell,” says Guillory.

One highlight in my romance genre journey was going to The Ripped Bodice in Culver City, California, which was the first bookstore devoted to romance in the U.S. when it opened in 2016. I was in town a couple years ago for work and made time to pop in before my flight home. This was a store that not only sold romance books, but had space for feminist books, conducted an ongoing survey of race in romance, and had an in-on-the-joke name. I walked up to the counter and said I was brand-new to romance but really loved Jasmine Guillory’s books. The woman working asked if I liked certain tropes, like enemies to friends. “Maybe?” I said. “I mean, probably.” She walked around the store grabbing books and I got on the plane with five authors I’d never heard of.

I called Leah Koch, who owns The Ripped Bodice with her sister Bea Koch, to see if she could take me through an abbreviated history of the genre. “You could argue Shakespeare has romance, but Jane Austen wrote the first romance novels,” Koch says. “Pride and Prejudice is the first classic romance, which is a central love story, happy ending, where that is the whole point of the book.” There’s Georgette Heyer, who “essentially wrote Jane Austen fan fiction” in the 1920s; Harlequin starting in the 1950s; the late ‘70s, when you see a shift from short to long novels and sex in romance; the Fabio-style “clinch covers” of the 1980s; the Nora Ephron adjacent illustrated “chick lit” books of the ‘90s, where romance started to get mixed in with so-called “women’s fiction,” with shopping bags and little dogs on their covers. “The genre keeps expanding,” Koch says. “After Trump’s election people were all over Twitter saying romance is what we need right now.”

In romance, a happy ending is guaranteed, unlike in real life. That’s a key part of the appeal. Helen Hoang, whose book The Kiss Quotient, about an autistic female engineer who hires a male sex worker to explore intimacy was one I picked up at The Ripped Bodice, told me that happy endings are crucial. “When I read a book and I don’t know it’s going to have a happy ending, I brace myself and guard my heart and don’t want to get hurt,” she says from her home in San Diego. “In romance, I have that trust that the author is going to take me on a ride but it’s going to be okay, which makes the experience more intense. You give up that control.”

Even though romance is pure escapism, that’s not the only appeal. On a deeper feminist level, they’re a way for readers to navigate being a woman in the world. “You can look at the romance from 20 years ago and it’s very different from today’s romance,” Hoang says. “There’s much more emphasis these days on consent and women being direct about what they want.”

A book that totally upended what I thought of romance was Rosie Danan’s book The Roommate, which is about a sex worker and a trust fund girl with a Ph.D. in art history sharing a house in L.A. The characters are unapologetic about their lives and work and the novel is whatever the opposite of prudish is. (I’ll just say that dry humping never seemed all that sexy to me before reading it.) “I think it’s a bit newer to have sex work handled in a way where the whole book isn’t about redeeming the sex worker or stigmatizing him,” Danan explains. I was delighted when she told me her book was a twist on a historical romance trope. “I wanted to translate the historical trope of ‘lessons in seduction between a rake and a bluestocking’ to a contemporary story. It’s the sexually experienced, really confident male character and the over-educated wallflower, and he is guiding the bluestocking into what her pleasure looks like.” See also: Bridgerton season 1.

Tropes are big in romance. There’s a knowingness about them that I condescendingly assumed was something fans had to overlook. Instead, they‘re embraced. The Ripped Bodice sells book sets around them, including “Can You Zip me Up?” and “There’s Only One Bed.” “There are so many in-jokes, like does your hero even exist if his broad shoulders don’t fill out a door frame at least once?” says Danan.

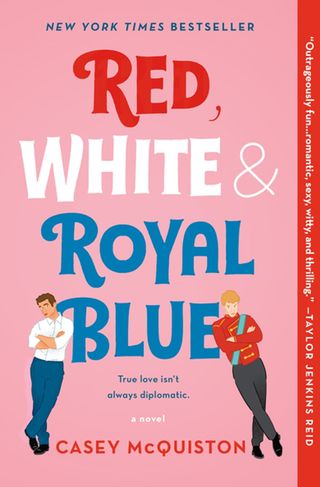

“Romance is a pleasure space. Your characters are allowed to have fun,” says Casey McQuiston, who wrote the New York Times bestseller Red, White, and Royal Blue about a Prince Harry-like character who falls for the son of the U.S. female president—pure wish fulfillment. She has another queer romance, One Last Stop, coming out in early June. “Queer characters can be messy and still get off. It’s a space to express and depict types of sexuality people may have been shamed for or not be aware of,” she says. (Her tip for writing sex scenes? “If you don’t think it’s hot, I don’t think the reader will.”)

So, will the events of 2020 make it into my new favorite genre? I asked Guillory what she planned for her sixth book, While We Were Dating, which comes out this July. “There is not a pandemic in this book. I talked to other writers about this. It’s impossible to write about something I’m currently going through, and there are a lot of emotions I’m dealing with,” she says. “I write books with happy endings, and we’ve got to find ourselves a happy ending. In many ways writing this book was my escape from everything, and I didn’t want the current world to infringe on my escape.” And until I get a vaccine, romance books will continue to be mine. At least we’ve found each other.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io