This year has offered a rare opportunity for many artists to slow down, reflect on what they value most, and delve deeper into their creative process. “Coming up for air,” (followed by a turtle emoji) is how rising star, Oyinda, describes the current state of her creativity in an Instagram bio. But for the London-bred, New York-based musician, reprioritizing her artistic experience comes naturally—no matter what year it is.

In my conversation with the independent British-Nigerian artist, who sings, writes, and produces on the bulk of her eclectic electronic soundscapes, a meditative sense of intention is evident in every aspect of her complex artistic process. In some ways, our dialogue echoes conversations that have opened up online about recognizing the totality of the Black life and experience—it’s really this rich fullness of Black expression that guides our discussion.

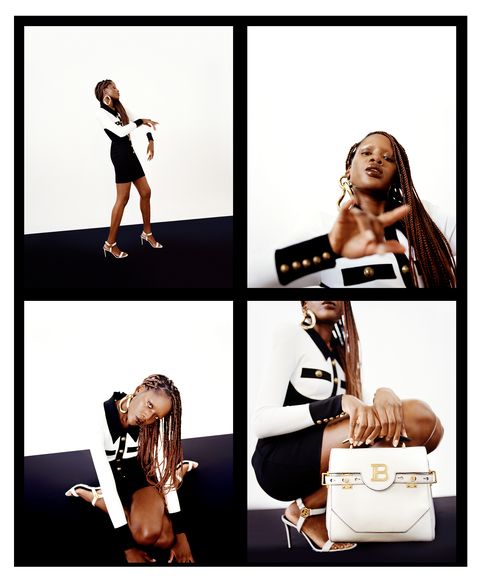

From the moment she released her last EP, Restless Minds in 2016, her creative universe ballooned beyond the recording studio. That EP’s slinky, cinematic arrangements, paired with Oyinda’s experimental visual style, was quickly embraced by New York’s music, art, and fashion worlds. Soon she was collaborating with other artists, part-time modeling for predominantly POC-led it-brands, and headlining the New York Fashion Week scene. Her creative fluidity and dimension—not to mention her continued commitment to partnering with groundbreaking POC innovators—made her the perfect match for Balmain and this story in support of the brand’s B-Buzz bag.

Oyinda’s voice is deeply interlaced with the visual arts. And when it came to her bread-and-butter—music—Oyinda found inspiration in the work of a renowned Black contemporary painter. The artist’s large-scale scenes and sculptures, which depict the nuance of Black American life and culture, became the muse for Oyinda’s new music—a mixtape of samples that she says has been in production for years and will be a “shedding of skin” preceding her forthcoming debut album.

“I now have the space I need to make the music I want to make without pressure,” she says. “In the music industry, you are programmed to just release, release, release, which has never gelled for me as an artist. I’ve always valued taking my time on things that are so specific and intricate and personal.”

Oyinda’s process makes perfect sense to me. I too am a Black independent musician who writes and co-produces my own material, without the resources of a major label. For both of us, there are “normal” artistic standards and expectations of “perfection,” but they are always far higher for Black artists than our white counterparts. In an industry that often pits Black femme artists against each other (see: you’re either Queen B or bust), it’s revolutionary to remove oneself from the noise and focus entirely on craft. As the primary architect of her career, from production to creative direction, Oyinda’s output is restrained only by her own creative capacity. This daring autonomy over her work leaves Oyinda free to present herself authentically to the world. Doing things her own way allows her artistic dimension to be seen fully and powerfully as a Black artist.

“I’d rather just post something and delete it or archive it rather than have something out that I’m not 100% behind. It’s my name on it at the end of the day,” she says.

That “post-and-delete” mentality also makes sense when thinking about the complex and highly curated visual medium that most influences Oyinda’s work: film. As a child, Oyinda grew up watching Japanese manga and anime, drawn to the genres’ storytelling, score, and art. It became a full-blown obsession that continues to this day, and now she jokes that it “worried” her traditional Nigerian parents, who wanted her to become a lawyer.

I share that when first I made music as a teenager, my Black American father teased that I shouldn’t “quit my day job.” To which Oyinda responds, laughing, “Now my mom especially just stands back and watches what I do next, almost out of curiosity.”

Oyinda is definitely one to watch. Her music videos are just as hypnotic as the slow-burning poetry accompanying them. One of them, “Serpentine,” brings to life the therapeutic concept of hypnosis, with black-and-white imagery of Oyinda as a patient visualizing herself outside her own senses. “Behind his way, in silence/ Lies a vacant space,” she sings. “He hides between desire/And a will to fade.”

As the video transitions to color, the song explodes into whirling synths, and Oyinda is a VR version of herself, hyperreal, and transformed into something new.

“I like to think that when I’m creating each moment, I’m also scoring my life; I’m scoring my day-to-day; I’m scoring my lyrics,” she explains.

This level of creative observation and discipline is applied to Oyinda’s personal style, a harmonious fusion of masculine and feminine energies. She can be seen in tailored military-style jackets with pointed shoulders and regal, diaphanous gowns accentuating her frame. Considering Oyinda’s broad musical inclinations and her relationship to daring fashion, she’s like a modern-day muse—not far from the Studio 54-era style icon she admires.

The power and fluidity of Balmain’s latest collection couldn’t be a more ideal match for Oyinda’s ever-evolving sense of expression, and yet, as an independent artist, she was stunned to learn her work was supported by the French luxury house.

“It’s been a blessing,” Oyinda says. “Olivier Rousteing is one of just two Black designers of a major fashion house, which is major, to begin with…The work and the toll it takes to uphold that position can only be respected. There is a regality in the collections by Olivier that I have always been drawn toward—there is structure, and also androgyny.” However, as a Black creator building her own legacy through music and visual art, Oyinda connects most strongly to Balmain’s enduring sense of royalty.

“[Balmain] is like an empire unto itself,” Oyinda says. “That’s what the clothes make me think of. And even if that empire someday falls, evidence of it will always remain.”

All Ready-to-Wear and Accessories by Balmain; Fashion direction by Cassie Anderson; Makeup by Mark Edio; Art direction by Sonja Georgevich