Black people are resilient, but our wounds have not disappeared. Instead, they’ve been ignored, left to fester, so we can continue trying to survive in this world. But every so often, those wounds reopen, and we’re reminded of the ongoing charade. Today, the centennial of the Tulsa Massacre, is one such day.

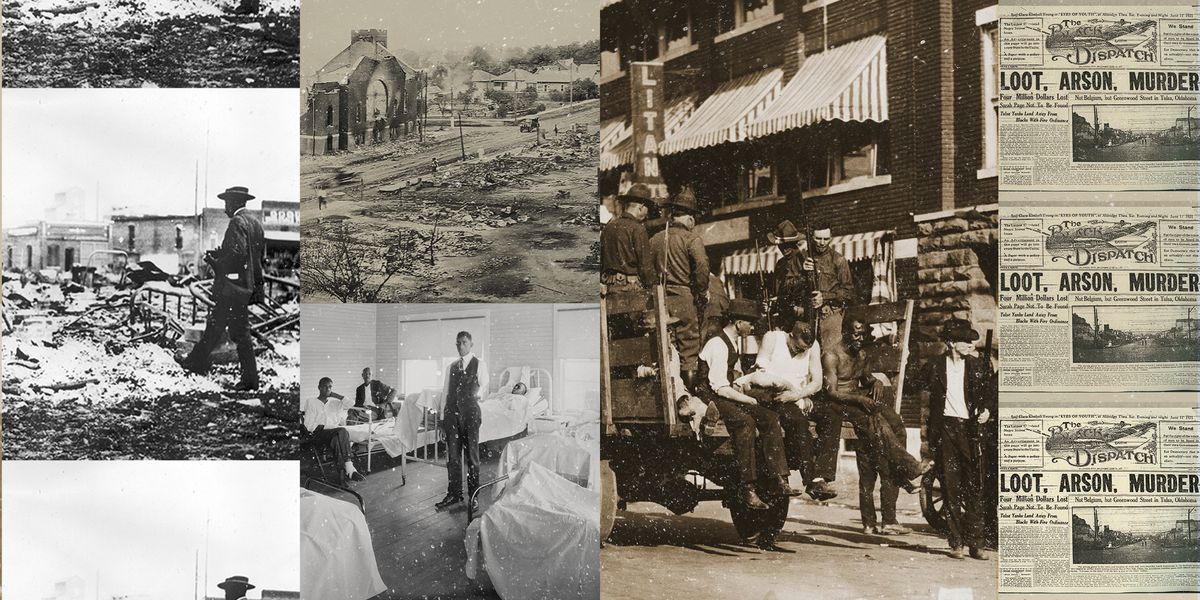

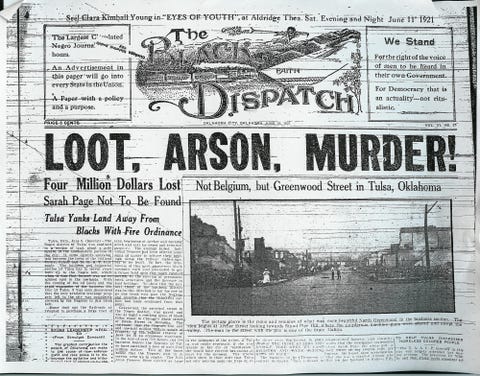

Centennials are typically celebrations of legacy, tradition, and history. But today we mourn, as 100 years ago, the community of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was all but leveled to the ground, and Black Americans everywhere paid a price. The body remembers.

It all began with the wrongful arrest of a young Black man accused of attacking a white woman. Upon his arrest, angry Black community members took up arms as a show of defense for the young man, and angry white mobs gathered around demanding “justice.” When all hell broke loose and the Black people present began to retreat, it turned into a massacre in every sense of the word. In the span of 24 hours, it’s estimated that more than 800 people were injured and as many as 300 Black people were killed. Part of the reason these figures are estimated is because after 35 city blocks were burned to the ground, some accounts recall bodies being thrown into the Arkansas River or buried in mass graves.

When the National Guard finally began to take control, they arrested every Black person in Tulsa not already jailed; an estimated 6,000 people were detained, some for more than a week. Upon their release, they returned to their community as refugees. The white vigilantes who took everything from the Black people of Tulsa were never held accountable. An all-white grand jury indicted 85 people, most of whom were Black, for “rioting.” It wouldn’t be until 2001 that an official commission would honestly investigate and review what transpired, discovering that “agents of government” were a part of the violent onslaught—not exactly a revelation for any Black person. Our bodies remember.

Nobel Prize-winning writer Toni Morrison often reflected on the trauma Black people carry, how it swells and grows with time. It’s so heavy and burdensome that even when we aren’t acutely aware of its presence, we’re still weighed down. Morrison highlighted this in her work, opting to only tell stories centered around Black people, so we could see and heal ourselves through her words. “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was,” she once stated matter-of-factly. At the time, she was referring to the Mississippi River, but her words ring true for the water within us, keeping us alive and remembering all we try to push down.

To truly comprehend the daily reality of Black people, one must understand historical trauma, defined by Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart as “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma.” In a 1999 study, Dr. Brave Heart focused on the historical trauma response among the Lakota people, who have faced long-term emotional consequences after living through genocide and forced family separation through boarding schools. Similar research from Dr. Joy DeGruy shows that “generations of slavery, segregation, and institutionalized racism…has contributed to physical, psychological, and spiritual trauma” for Black people.

A number of marginalized groups, from the descendants of Holocaust survivors to children of Japanese Americans interned in camps, have been studied to better understand the intergenerational effects of systemic persecution. Too often, we avoid difficult conversations in favor of convenient tales such as “post-racial America” or impossible directives like “let go of the past.” But as William Faulkner famously noted: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” We can’t move on from what hasn’t been addressed nor healed, and we certainly can’t move on from what never ended to begin with. Tulsa, like traumatic events before and since, is still branded on our psyche.

As a country, we tend to obsess over figures and numbers, while losing sight of the human beings whose lives were forever changed when they saw vigilantes and law enforcement alike take up arms against them in their own homes. Those who survived could never again feel a sense of security after watching their neighbors shot dead in the streets and local businesses and edifices engulfed in flames. Some describe hiding under dining room tables and beds while their homes were ransacked and priceless memories and heirlooms were destroyed. According to a lawsuit filed last year, Lessie Benningfield Randle, a 106-year-old living survivor of the Tulsa Massacre, affectionately known to her community as Mother Randle, suffers “flashbacks of Black bodies that were stacked up on the street.” The complaint continues, saying that Randle “has struggled financially, emotionally, and socially as a result of the continuing public nuisance.”

Many fled to wherever their feet could carry them and never looked back. Some stayed in Tulsa, choosing to rebuild their lives in the city that now included their most painful memory as a tourist attraction. Those who survived saw the ruins of their lives rezoned to create space for industrial use. They would tell their children and their grandchildren and their great-grandchildren about the relentless nature of white supremacy. And those kids grew up to see the truth of those warnings in their own lifetimes. The lynching of Emmett Till. The assassination of civil rights leaders. The criminalization and mass incarceration of generations. The attacks on our churches and cultural centers. The viral brutality against our children for all the world to see.

That is how historical trauma works. That is why Black people can’t simply “move on” from the oppression we, our parents, and those before them faced. Most, if not all, Black Americans carry stories of racist violence. Sometimes, those stories are passed down through oral tradition as a warning of how far white America will go to subjugate us. Other times, that pain is felt in heavy-handed parenting or tough love, seeking to protect Black children from a world that sees them as anything but. Most times, the trauma is reinforced when we see how little has changed. We think of the country we bring children into and grow old in. The myth of slow progress haunts us because we know we’ll be the ones picking up the pieces when the violence outlives those promises.

Through clenched teeth, sleepless nights, irregular appetite, and stress, we remember. During uprisings or while trying to take our mind off of things, we remember. And each time another Black child or parent or sibling or friend is taken from this world—whether by police or an inept healthcare system or vigilante violence—we not only remember, but the pain is further compounded. Because with each new day, there are more injustices tallied, more trauma cemented, and more trust broken. Those who consider themselves allies can take this as a call to action: Reparations in any sense must include addressing our intergenerational trauma and providing the resources for healing justice. The moral debt owed to Black people is one America can’t afford—and also one that America can’t afford to not address.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io