What does it mean to be a Black woman in America? On the one hand, we are absolute magic, influencing everything from fashion to music to culture. And as we saw in the last election, sistas have the political power to shift elections and save this nation’s democracy and nation from itself. However, as Malcolm X once said, we are also still “the most disrespected person[s] in America.”

Even in that, we persist, and Oge Egbuonu’s new documentary (In)Visible Portraits (now streaming on the OWN app) beautifully conveys that sentiment. In her directorial debut, the movie-producer-turned-director seamlessly weaves together first-person interviews with everyday Black women, razor-sharp analysis from beloved Black cultural critics, and a historical perspective of our collective journey in this country. Most importantly, Egbuonu isn’t afraid to go there, touching on a range of issues including the intersections of race and gender, colorism, reclaiming our bodies and sexuality, dismantling tropes such as the “angry Black woman” and the “Jezebel,” and the lasting impacts that slavery and medical racism have on Black women. Thankfully, Egbuonu’s vision doesn’t sit in darkness the entire time; she makes sure to carve out space for Black joy, happiness, and optimism for our bright and promising futures.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

ELLE.com sat down with Egbuonu to discuss the process of making her love letter to Black women, why it’s our birthright to own our anger, and why her film feels right on time.

How did you get involved in filmmaking?

I taught yoga, breathwork, and mediation, and a private gym asked, would I be interested in doing restorative yoga for a VIP client? At the time, I didn’t think I had the capacity, so I declined. They offered to pay me triple and I still said no, but when my schedule cleared, I said yes. The client was Ged Doherty, former chairman at Sony Music. One day he asked me if I ever thought about working in film. I immediately said, “absolutely not.” [Laughs]

He then told me he started a production company with actor Colin Firth and would love to bring me on, and I was like, “Who?” [Laughs] I honestly didn’t know anything about the film industry. But I sat and meditated on it for a few weeks, and my mom suggested trying it for three months, so I accepted. At first, I was running errands, but I went to London for two weeks, and what really sold me was talking to Colin. He shared that there are so many stories he wanted to tell, but as an actor, he can only play a white male, but he can help others tell their stories as a producer. That really resonated with me.

Since then, you produced the 2016 Oscar-nominated film Loving and have dabbled in acting. How did those roles prepare you for your (In)Visible Portraits directorial debut?

It taught me the power of storytelling and how it can truly be powerful and transformative when it’s done correctly in this medium. I knew that to tackle a broad and intense topic, it had to be right: I had to know the subject matter. I went into nine months of research, six days a week, 14 hours a day, reading books and immersing myself in library archives. The only day I didn’t do that was on Sundays, and on those days, I would be in bed crying until 4 p.m. When you’re reading slave narratives about 9-year-old-girls being raped, it takes a toll. I had to put myself in therapy, and it really saved me and helped me process how to create this film and how to tell these stories and tell them with intention.

As a Black woman labeled “angry” more than once in my life, I appreciated that the film began with a discussion about our rage and our right to own that emotion. Why was that important?

Anger has been a weapon used against Black women and yet anger is such a human experience that most folks are allowed to experience except us. I wanted to address that head-on. We have the right to be angry and have so much to be angry about, so it’s important to embrace that and to socialize us to embrace that—it’s our birthright. Only a white supremacist society could dehumanize us, make it harder for us to develop a sense of worth and then project on us that anger isn’t allowed.

I also love that the film carves space for women to talk about their individual and collective joy—something we all could use, especially now.

From the beginning, I wanted (In)visible Portraits to create a full spectrum of what we are in this world. Yes, that includes suffering and pain, but it also includes joy and the importance of healing. As Black women, we carry so much, give so much to other people, and in return, we walk around with our cups so empty. We need self-recovery and happiness, and highlighting our joy is so important—it humanizes us. Yes, in the doc we talk about how we have been dehumanized, but we end by reclaiming ourselves and celebrating each other.

The power of your film is the voices and the vulnerability of these everyday Black women. How did you get them to sign on and trust you?

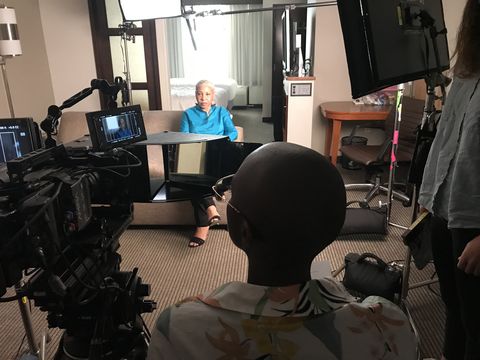

I didn’t want to use celebrities. I only want scholars, authors, and everyday women. My assistant reached out to non-profits that catered to Black women and girls, and I got connected with Sheila Thomas from the Watts Labor Community Action Committee. But she made it very clear that folks come in, exploit their stories, and they never hear from them again. So, she would introduce me, but it was up to me to build my own relationships and trust with these women and girls. I spent a lot of time getting to know them but making it very clear that there was no obligation to be in the film. Lucky for me, after a few months, they wanted to take part and I am very blessed that they said yes. I also believe that having an all-female crew helped create a safe, soft, and tender environment that fostered the openness that you see on the screen.

You started making this film in 2016, and yet it feels right on time, especially as we approach the first anniversary of Breonna Taylor’s death.

(In)Visible Portraits feels more relevant and more important right now, but it’s also a timeless piece. Black women have carried and continue to carry this society on their backs as we understand that no one is free unless we are all free. It’s up to us to liberate ourselves and, in turn, the rest of society. Just look at Black Lives Matter. Created by Black queer women. Most of the organizations that are saving our democracy right now are led by Black women. That’s us.

While we are in a sad time filled with so much injustice, it’s also a beautiful time as we are reimagining ourselves, our art, our impact and our power. This is necessary because we have so much at stake. We have speak our truth and step into our power in order to dismantle the system. This film honors and speaks to all of that.

Finally, why is the “in” of invisible in parenthesis in the title?

No one has ever asked me that before. [Laughs] The parentheses are important because it represents history. While society has gone out of its way to dehumanize Black women, it’s built off Black women. So despite trying to render us invisible, erase us, and break us down, you can’t. We will always be seen and shine. It’s embedded in our DNA.

(In)Visible Portraits is streaming for free on the OWN app during the month of March and will re-air Saturday, March 13 at 12 p.m. ET to mark the anniversary of Breonna Taylor’s death.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io