Last year I took my first trip to Ghana. What was supposed to be a 10-day trip of rest and relaxation turned into so much more. Instead of spending the last few days partying, I made the last minute decision to visit Kokrobite, a beach town just outside the capital city of Accra. Standing on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, I felt captivated, mystified even, watching kids surf. While I was familiar with the sport—my interest dates back to the 2002 release of Blue Crush—this was unlike anything I’d ever witnessed. Black bodies gleefully bobbed and weaved with the pulse of the ocean, the same one our ancestors had been forced to leave centuries before.

They moved with such joy and ease. I wanted to feel that, too. A reprieve, even if for a few moments, from the exhausting burdens placed on Black womxn, like the fear of being killed by police while we sleep. In a world that can feel suffocating, moments of solace are life-saving.

Weeks after returning stateside, I booked my first surf lesson despite the remnants of a frigid East Coast winter that hung in the air and clung to the water. It didn’t matter that it took nearly two hours and a shuttle connection to journey from the cacophonous streets of Harlem to the murky forest-green waters of Rockaway Beach. The joy and peace I felt back in Ghana was now within my grasp. Shuffling into the water, zipped securely into a rented wetsuit, I clung tight to the Styrofoam board connected to my right ankle. I felt uneasy: I was now at the whim of the ocean, and realized I was the lone Black student in a class full of stereotypical surfer types.

As I learned how to push myself up and glide one foot in front of the other into an awkward sumo stance, perfectly timed with the rise of the ocean’s kinetic energy, I thought of Ghana. Communities of the African diaspora, more specifically on Africa’s Gold Coast, have been surfing for centuries—the earliest record dates back to 1640, nearly two centuries before it was practiced on American shores, according to Kevin Dawson in his book Undercurrents of Power. Yet Black people are almost always absent in historical and pop culture renderings of the aquatic pastime.

The transatlantic slave trade generationally complicated our relationship with water, and for some, this turbulent relationship remains. Segregated beaches and pools in the 1950s and ’60s meant that Black folks’ access to water was limited at best. The opportunity to learn how to swim or be introduced to aquatic sports like surfing didn’t really exist. Not surprisingly, a generation of Black folks grew up either afraid or unaware of the water’s ability to heal. But despite our erasure from the sport, there seems to be a growing enthusiasm amongst Black womxn for the water, and surfing in particular. Instagram accounts like @BlackGirlsSurf, @BrownGirlSurf, and @TexturedWaves are helping to normalize images of Black bodies riding waves.

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

I believe it’s the inextricable place of water in our history, from the shores of Africa to our passage to America, that has led to womxn like myself and LA-based journalist Darian Symoné Harvin to embark upon a sport in which we rarely see ourselves represented.

“I’ve always loved the water and been a huge daredevil,” Harvin says, “Surfing felt like the sort of sport that would take some time to get good at. I was up for the challenge.” She says that standing on a shoreline makes her forget her skin color and instead reminds her of the infinite possibilities available to her. Surfing reminds her of her humanity in a society that doesn’t give it willingly, and inspires her to take up space instead of feeling small, something I also experienced learning how to ride waves.

Black womxn earn 38 percent less than white men and 21 percent less than white women and often suffer from compounded discrimination. Erica Chidi, a health educator and CEO of the community-based education center LOOM, told me that “the baseline for Black womxn is stress.” She adds that “Living in a Black body and how society perceives [that] body makes very mundane, very routine activities have an underpinning of extreme discomfort.”

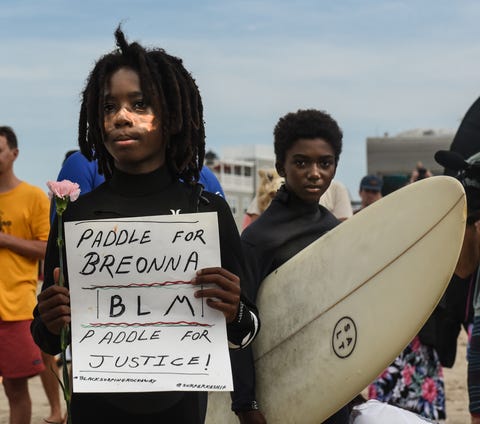

Traversing life with racially induced anxiety—because not doing so can have dire consequences—and being asked to explain things on behalf of an entire race quickly becomes tiresome, especially lately. As this country has begun to confront its racist past over the last few months, the brunt of the work—in the form of tough conversations about white supremacy and organizing to dismantle it—has fallen on Black womxn. Earlier this summer, the Black surf collective Textured Waves, like other surf groups, began organizing paddle outs in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. At one of these events in June, more than 300 surfers paddled out to chant George Floyd’s name and sing “Happy Birthday” to Breonna Taylor on what would have been her 27th birthday. Although their goal was to use something they love as a meeting ground for unity and peace, the group was still met by the New York City Police Department.

And yet, floating in the Atlantic Ocean or riding waves in Hawaii provides a kind of peaceful interlude, if only for a moment. It’s this feeling that makes water transformational for Black womxn like myself, Harvin, and Chidi.

Pro surfer Dominique Miller, who goes by Nique, is intimately familiar with the joy of escape. Often the lone Black womxn in the line-up at competitions, her presence is sometimes perplexing to both fellow competitors and spectators. For her, it’s an act of resistance.

“Surfing makes me feel completely free. And I feel really, really happy while doing it,” she says. Miller has surfed across several continents since her teenage years. That feeling, the kind that comes from being challenged and reshaped into a more confident and alive version of yourself, is why she continues to compete after five years, even as her competitors and peers remain mostly white.

The irony of Black womxn finding respite in the water despite our complicated history isn’t lost on Harvin and Miller. Both say that their parents wanted to expose them to aquatic activities early. “My mom and dad were very aware of this stigma that Black people typically don’t know how to swim, so they made sure I knew how to,” Harvin says. She first learned how to swim as a toddler at her local YMCA. Miller, too, was enrolled in swim classes before she could even walk.

Despite bearing the brunt of constant inequality, Black womxn are taking the adaptability honed in the water and using it to bolster themselves against the aggression they face on land. While my deep love and appreciation for the water didn’t develop until adulthood, it’s been no less transformational. In the last few months, as the world has become exponentially more stressful, surfing has felt even more imperative. Instead of trekking to the beach from Harlem to Queens each week, I moved across the country to be closer to water. In Los Angeles, I’ve found a community of surfers who together seek daily reprieve in the water.

After spending three decades twisting and contorting myself into a person who’s always on guard against the next racial aggression, be it macro or micro, I was desperate for something that would allow me to exist in my fullness and just be. The rush that washes over me when I glide down a glassy wave, even for a few seconds, is a sense of freedom that’s become sacred.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io