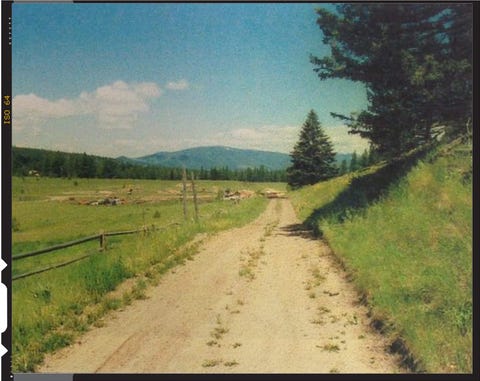

For nearly two decades, Ted Kaczynski carried out a deadly bombing campaign against those he believed to be destroying the environment and furthering the advancement of modern technology. The former UC Berkeley math professor was able to carry out his reign of domestic terror from rural Montana in a secluded 10-by-12-foot shack, where he tested homemade bombs and compiled hit lists. In 1996, Kaczynski was captured at the cabin and sentenced to eight consecutive life terms in prison with no possibility of parole.

The “Unabomber,” as Kaczynski is known, was the “perfect, anonymous killer,” according to the FBI. He was so innocuous, so untraceable that even those who lived nearby never suspected him of murder. In her new book, “Madman In the Woods,” (April 19, 2022, Diversion Books), Kaczynski’s next door neighbor—and one-time friend—Jamie Gehring opens up for the first time in intimate detail about the “silly” recluse down the road. Below, in her own words, Gehring remembers her relationship with Kaczynski, and the guilt she shouldered after finding out he was the Unabomber.

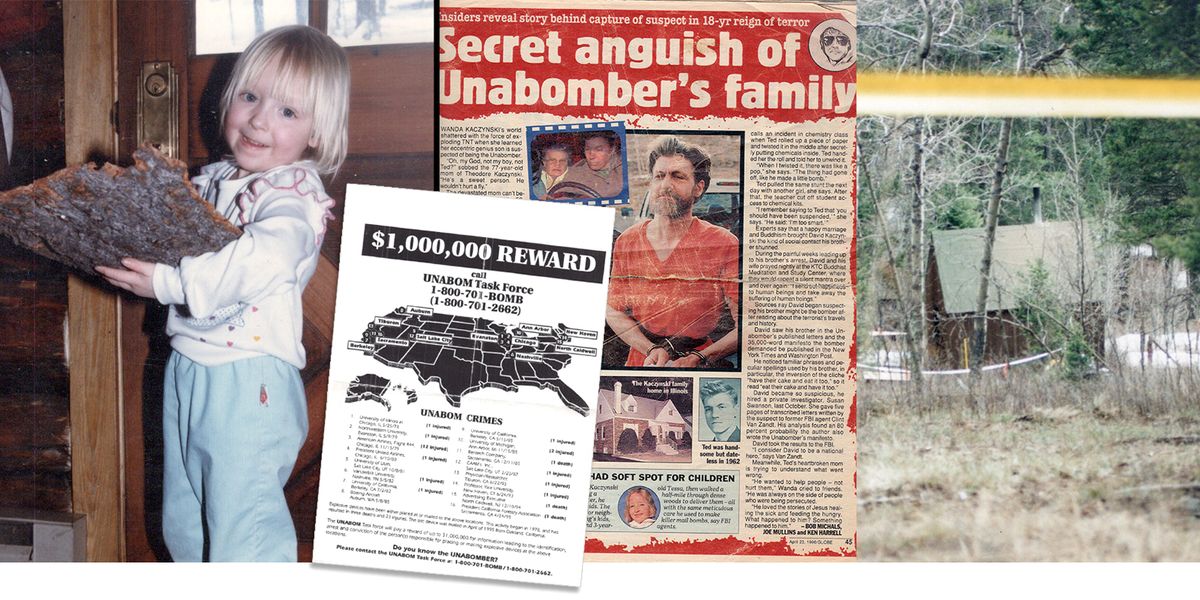

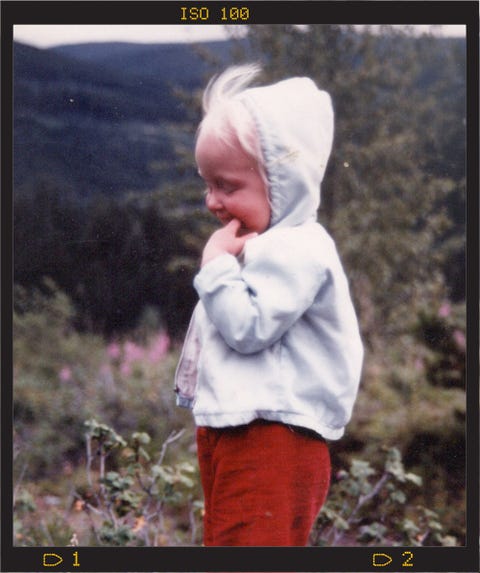

One of my earliest memories of Ted Kaczynski is a happy one. I was playing outside—I must have been around four years old—when he appeared out of nowhere. He tended to do that. I was so excited to see Ted. Back then, in the early ‘80s, he was just this silly, strange neighbor who lived in an isolated cabin near our home in Lincoln, MT. He’d stop by for dinner with my parents, and then play cards with me. Our family considered him a real friend, and he had become something of a regular fixture in my life.

That day, he knelt down and opened his hands to reveal a painted rock. Ted had brought me a gift! I felt so special, and so appreciative. I loved rocks as a little kid. And this one was just for me.

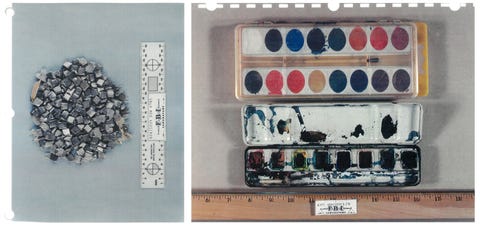

I don’t remember what was painted on the rock. Neither does my family. But many years later, I discovered a picture taken by the FBI after they raided his cabin. In the image, Ted’s paints are sitting next to the fragments of the metal he put in his deadly bombs.

I know it’s just paints, but that photo is a symbolic juxtaposition of who Ted Kaczynski is to me: He’s Ted, the guy who brightened my day with colorful rocks, but he’s also the Unabomber, a monster who terrorized the nation.

When Ted first moved to Lincoln in 1971, he still had a “disheveled professor” kinda look. But by the time I was born in 1980, he had begun to look more like a wild man. His clothes were torn and falling off of his body. He always had mud under his nails. His hair stuck up straight up, and his eyes were very wide. I remember looking down, and not being able to tell if the dirty things below his ankles were his shoes or his feet. Upon further inspection, they were his feet. His shoes had basically rotted away. He was completely unkempt.

As time went on, Ted’s appearance only got more extreme—and so did his behavior. In the early 90’s, around the time I was 10, Ted started to come over and ask what time it was. I don’t know if it was because of his change in look, his change in cadence, or maybe the fact that I was older and more aware of the world around me, but I became afraid of him. He never seemed right. He was always in a hurry, and frenzied. If he came by the house when I was alone, I would hide in the closet until he left.

Looking back now, I was right to be afraid. At that time, Ted was at the height of his reign of domestic terrorism. He was holed up in his cabin, testing bombs and writing his manifesto. He was killing people, and then knocking on our front door to ask for the time.

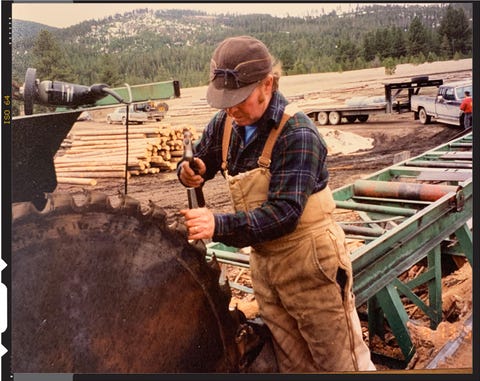

Ted’s relationship with my family began to deteriorate, too. My dad owned a sawmill, and Ted was clearly bothered not only by the industry of logging, but also by the noise it created and the outsiders it brought so close to his cabin. I’ve been asked whether I think the noise of our mill fueled Ted’s anger. That’s a difficult question to answer, because, yes, most likely it did—but so many things fueled Ted’s anger. Jets flying overhead. The presence of forest rangers.

The conclusion I have come to is that Ted was inherently angry and very violent. Just because he heard the noise of a sawmill or saw logging happen close to his home, doesn’t mean we should be held responsible for his actions. Ted Kaczynski was responsible for Ted Kaczynski’s agenda—not the people around him who were trying to live their lives and make an honest living.

Another question I get is: “How did you not know?” There is a certain amount of guilt I feel, because for so long my family unknowingly lived near this very dangerous person. But Ted did a great job of blending in. He was methodical in where he purchased his property and how he chose to live. I think that’s partly what enabled him to carry out his agenda for so long.

Looking back now, though, I see the signs. As a kid, I used to hear somebody walking and whistling outside my window at night. Then, I’d hear metal moving around. I would run into my parents room, and tell them someone was out there. My dad would say, “There’s nobody, go back to bed!” It was chalked up to an overactive imagination. But now I know it was Ted. He was scavenging pieces of metal from my dad’s old cars and used equipment out by the sawmill.

I think it’s one of the reasons he was able to remain untraceable for so long. He wasn’t buying metal from a hardware store. He was finding pieces, melting them down, and using them as shrapnel for his bombs. People joke about monsters being under the bed at night, but for me he was outside my window.

During the ‘70s and ‘80s, a couple of mines and properties in Lincoln were vandalized. My father’s sawmill was sabotaged by somebody who poured sand into it. It remained a mystery until 2020, when Netflix released Unabomber: In His Own Words. In the documentary, Ted admits that he tried to shut down my father’s business.

Around that time, our family dog, Wiley, got sick. Wiley was incredibly sweet, always going on hikes with me and playing outside. But there was something about Ted he didn’t like. If Ted was riding his bike by the sawmill or walking up to the house, Wiley’s hackles would raise. He barked and chased him. It was almost like Wiley turned into an entirely different dog when Ted was around.

When Wiley got sick, the vet said he ingested strychnine, which destroyed his immune system. Wiley ended up passing away from health issues related to being poisoned. When authorities searched Ted’s cabin years later, they found a stash of strychnine. Ted also wrote a letter to a local newspaper after his arrest, mentioning that he had poisoned a local dog that came into his garden at times.

These are just a few of the many acts of terror Ted carried out in our own backyard. Of course, they’re nothing compared to what he did on a national level. But for me, it was still heartbreaking.

In 1995, right before Ted’s arrest, my stepmother took my little sister Tessa into the woods with her to do some chores. They were reseeding the ground, when all of a sudden my stepmother got a horrible feeling that something—or someone—was watching her. She grabbed up my sister and got out of there. She could never shake that feeling, or that experience. In the wild of Montana, there’s bears and mountain lions, so it’s not out of character to run into wildlife. But she knew it was more than that.

While working on Madman In the Woods, I poured through thousands and thousands of pages of Ted Kaczynski’s journal entries and musings. He recorded daily occurrences, from his cooking to his hunting. He even had a designated crime journal, where he wrote in code. He recorded his victims as “experiments,” and kept track of the results of his bombings. It was almost like Ted was writing to an audience, the way he recorded everything. I don’t know if it was his way of communicating, or maybe there was a part of him that always knew at some point he would be arrested and all of these things he wrote would be public.

In one of Ted’s journals, I came across a reference to the day my stepmother and sister were in the woods. Ted wrote about how he had a gun pointed at them. He had contemplated killing them, but ultimately decided it was too close to home. He also didn’t want to take just one out and leave the other alive.

When I started Madman In the Woods, I was searching for answers about my neighbor Ted. I was interested in how the different interactions he had in his life made him feel—and how they shaped his actions. But I was also searching for answers about my family. My dad was a very private man, so I didn’t know much about his involvement with the FBI’s investigation until after he had passed away 10 years ago.

I recently sat down with the FBI officer who arrested Ted, who called my father the “eyes and the ears of the investigation.” My dad was like an informant. He let the FBI know if there were footsteps outside of Ted’s cabin, and if there was smoke coming out of his chimney. He updated them on Ted’s whereabouts and behaviors. The FBI even asked my dad to videotape the surrounding property and cabin. He was key to their investigation.

When my father was asked to do all these things, he knew that Ted was a potential serial killer. He also realized there were probably weapons in his cabin. There was some trepidation, of course, but my dad knew there was no other choice. He risked his life to help the investigation, and for that I’ll always be incredibly proud of him.

After the FBI raided Ted’s cabin in 1996, people started showing up to our house and asking to see where the Unabomber lived. My dad turned just about everyone away, unless, of course, they were affected by Ted’s violence. Most were families of his victims, some were people on Ted’s future hit list.

To this day, I’m still trying to make sense of who my neighbor was. Maybe part of the reason we’re not catching serial killers as quickly as we could is because they’re so capable of looking and acting normal. If you’re not touched by true crime or you have not lived it, you expect these people to be very obvious monsters.

That’s just not always the case.

They can still be capable of compassionate, human moments. Like when Ted painted that rock for me. Then I think about his hands. The hands that painted that rock for me are the same hands that crafted killing devices.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.