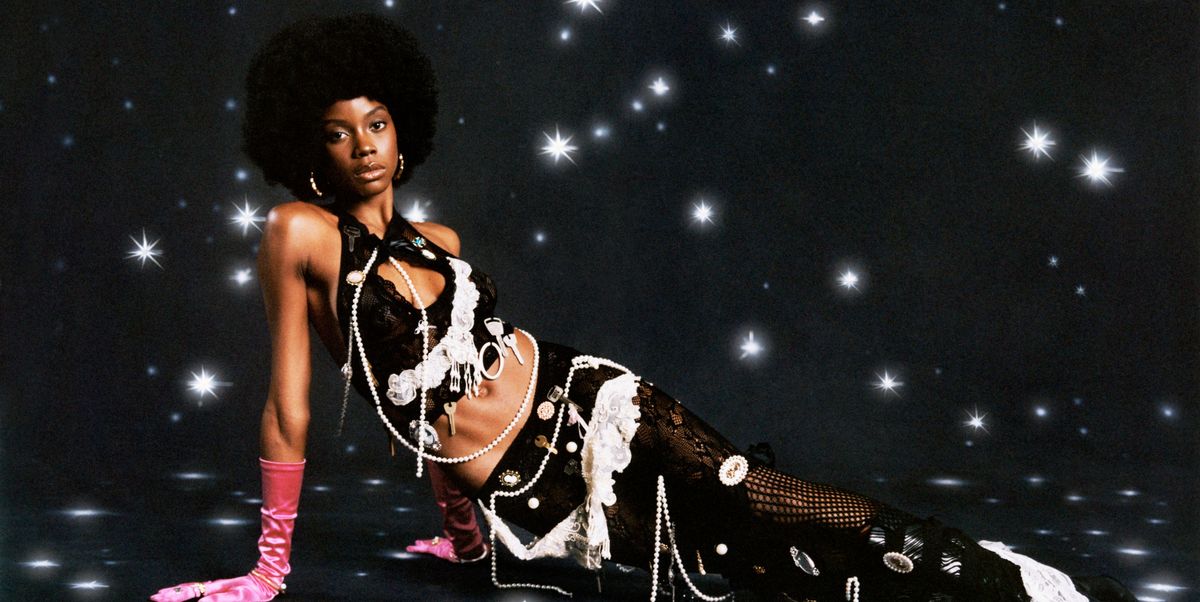

Micaiah Carter is at once youthful and wiser than his years. Case in point: The young photographer has already lensed the likes of Pharrell, Zendaya, Missy Elliott, and Jennifer Lopez with a careful composition, intimacy, and striking color balance that both uplifts and celebrates his subjects. Carter’s know-how has made him one of the most in-demand talents in the fashion and editorial sphere, and despite his fast track to the top, he has stayed rooted in family, storytelling, and community building to honor what it means to be a Black American today.

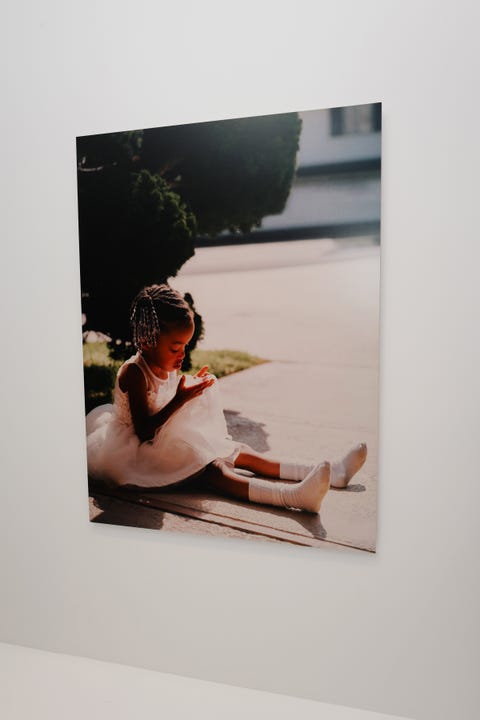

For his first solo show in New York, where he studied at Parsons and first began shaping his artistic ideas, Carter presents his editorial photography alongside imagery of his younger family members. After his father passed away last year, Carter dedicated the show, titled “American Black Beauty, Vol. I,” in his honor. The exhibit contrasts Carter’s current work with portraits of his nieces and footage from his father’s archive, weaving a rich story of family, history, and contemporary representation of Black beauty. He hopes that his nieces can see themselves in the high-fashion imagery, and that viewers can feel at home in the space, too.

Below, ELLE.com caught up with Carter to discuss his solo exhibition, the standards of Black beauty in America in contrast to the rest of the world, and how representation goes beyond the subject of a photo.

Congrats on the show! Is this a moment in your career where you feel like you’ve truly made it? Or was there another time when you thought, This is what I’ve been working for?

I don’t know, I still feel the same [laughs]. Maybe it’s because I’m an introvert and I’m not online, so I’m not tapped into the impact. It’s the nerves of, I just can’t believe that I’m having my first solo show after nine years of living here. I’m pretty excited about it.

I know your dad passed away last year, and I’d like to send my condolences. Was it a cathartic process putting the show together as a tribute?

Definitely. It definitely was something that [required] a lot of healing…a lot of things that I didn’t know, that I felt, or just kinda was avoiding in this show, and just doing this work. I think I’m probably closer to a point of acceptance.

How do you strike a balance between capturing a subject’s youthful energy and maintaining a level of maturity?

I try to be myself. My personality in general is a mix of those things. So, I try to keep mindfulness there so I can feel like I’m not tied down to age. I also feel like I really take photography seriously and I take what I do seriously, so that’s where it comes into play…all the prepping to get there, and then, when I’m there, that’s when I let the more playful things come out and give me life. Let’s shoot the amount we feel instead of having a whole plan, you know? I think letting go of expectations helps me do that.

Your work is reminiscent of a certain period in time while also looking to the future. How do you draw inspiration from the past, and who are your biggest artistic influences?

Being raised in the late ‘90s [and] early 2000s, there was a big influence of Black culture in general, where, from my perspective, it felt like we were in the future. Everything didn’t feel limited to the struggle or the last 40 years of Black existence, or the last six decades of Black existence in America. So [when] we got to the ‘90s [and] 2000s, it was really a sense of combining a lot of elements: the Black pride of the ‘70s, the sophistication of the ‘60s, the sounds of jazz, rhythm and blues, incorporating hip-hop, and embracing all of that.

Music is a big influence for me and my work. When I moved to New York for college, I got a really refined introduction to photography in a way that I wouldn’t have gotten if I had stayed in California—that’s what made me appreciate the fine art aspects of photographing people, celebrity or not. Looking at Carrie Mae Weems, Malick Sidibé, John H. White…these photographers are big inspirations to me. Black photographers, not only making space but also having an open dialogue about where we’re at, and having something for ourselves. I feel like it’s really special when we see those moments of collaboration. It’s super important.

What is your definition of American Black beauty?

To me, it means coming home: a sense of family, a sense of community. I was so specific about American Black beauty because I feel like Americans that are Black, from slave descendants, I think the culture and the rebuttal are just the existence of creating a unique culture. My American Black beauty is a world and its own feeling. Although we’re in America, I think it’s still very separate from the cores of American values—and I’m talking more politically than anything—but American Black beauty is the culture.

Being American is so specific, because there’s nothing else like it in the world, and that’s precisely what defines it.

A thing I noticed in the last couple years, which is great, is [that] Africa has become really popular, as has having it as a motherland base. But even with London Black creators, there’s a sense that they’re ahead in a way in how they think, because they’re not trying to heal wounds that they didn’t create themselves. Especially in America, there hasn’t been a real sense of moving past it, because no one has really talked about it in a way where it’s very important. My great grandfather was a slave, so all these things directly affect my family, and other peoples’ families. That’s why I wanted to focus on America so much.

How do you hope to continue pushing the needle forward in terms of representation, beyond having Black models cast in the show and casting Black models in a shoot showcasing Black beauty?

The contract and shoot are so important; those moments are still needed. But it needs to happen in a way where it’s not pigeonholed. Beyond shooting fashion and beauty, having people come together and experience a show publicly [and] having a moment where people can go into a space and really feel seen, not in a way that’s checking off a box, but in an authentic way, helps as far as what I can do. I’m not really into politics, but continuing to stretch and open the box for what a Black person is in America is the most important thing.

There are so many different ways to democratize beauty, and that can be political as well. Given your work with See In Black and your efforts to push for representation behind the camera, how else have you been working to broaden the scope of Black artists?

I think this is us coming together—that was the biggest thing. In bridging those gaps, so it feels like there’s a community base, there are resources, there is a network. That was something that I wanted to build, because some of that has never been done before. They did something similar in New York in the ‘70s, but having a coalition or a space where everyone feels represented, and let’s think not only about what’s in front of the camera, [but] behind the camera, and embrace all the diversity that’s in that— that’s what I want to see, and to be. This is America. Everyone’s experience is so different, because we’re all human. That’s what I wanted to go from.

SN37 plans to donate all proceeds from sales of “American Black Beauty, Vol. I” to Agent Orange Record in honor of Carter’s father, who was a Vietnam veteran. The exhibit is on view at SN37 Gallery at 204 Front Street in New York City until March 27, 2022.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io