For first grade, when we moved to Hudson, my mother continued the Latin family tradition of Catholic school for all. My brother went to the all-boys school one town away, Bishop Guertin, and I went to the all-girls Presentation of Mary Academy. I don’t remember much beyond being completely overwhelmed and unmoored. No one was brown like me, or Black or Asian, or had an “ethnic” name. I had trouble telling the girls (all white) apart. The uniforms were scratchy and ugly, a maroon, gray, yellow, and white plaid that would haunt me for decades. It was the first time I came into direct contact with nuns wearing habits, as all our teachers at the time did. The castle-like behemoth brick building was filled with them, navy or black skirt suits with veils allowing only a front pouf of hair or bangs to be seen. I must have spent that whole year simply processing. Processing and figuring it all out, managing everything coming at me, all the change. I do remember being feisty, though. My mother got an earful from the teachers early on. And then, when we moved again, it was time for a public school that was a bit more like home in only two ways: no uniforms and boys.

“No, my name is Morning Dove,” I insisted. “My mother made me change it when we got here!” I was seven years old and newly enrolled in second grade at the local public school. This ridiculous lie was my way of answering the new question “What are you?” Something hard for me to answer, because in New Hampshire I had already gotten the message that being anything but a white American was not good—not good—in these parts, a place where I was a drop of brown sap in a mountain of snow, or something else brown and not so sweet.

So, when my class had a Thanksgiving project to draw and color a mural representing the first Thanksgiving dinner, white people and brown people sitting at the same table together, I assumed there was not only equality in the depiction, but some kind of elevation of these brown people who looked like me and my family. I jumped on it. If these white kids were drawing and coloring Native Americans and the teacher was teaching us about them in honorable tones, well, I was just going to have to reinvent myself, wasn’t I?

“Your name is not that,” a boy sniped back at me.

“Yes, it is! You don’t know,” I cut him back.

I even designed a hieroglyphic name for myself, melding the influence of the Egyptian wing of the Met Museum with this new Thanksgiving myth. It was my first exposure to the holiday as far as I can remember. We certainly didn’t celebrate it back in NYC—the mass marketing and consumerism of the holiday had yet to influence our plantains-and-dumplings uptown immigrant bubble. The name I designed was an outline of a bird with half a sun above it. (Gotta give myself props for the mash-up.) Surely I made up this tale as a way to insert myself into the story of Thanksgiving that was obviously so important to these white American people. I saw myself only as the “Indian,” the brown one, that we drew and colored with crayons in our five-foot-long class mural. It was obvious that I wasn’t a white Pilgrim, characters that the whole rest of the class could see themselves in.

This identity I created was a delusion that I spoke of so much my teacher had to tell my mom at the parent-teacher conference. I don’t remember what my mother said to me afterward but I never mentioned Morning Dove or drew my glyph name again. But I also got no answers as to how to manage these feelings of being thought of as an oddity, a lesser human being, that this new place was pushing on me. And it pushed and it pushed.

Between my offensive appropriation and my embarrassing habit of tackling boys during recess to kiss them—and I do mean tackling, to the ground—Lupe had had enough of my shenanigans. It was back to all-girls Catholic school for me for third grade. And time to see racism trickle down from grown-ups. Back to the nuns and their habits, to scratchy uniforms and scolding for doing so much as staring out the window (which I did often). Back to the mostly French Canadian–named students and the military-tight lines of us walking down the halls, in forced silence, even to the bathroom. To Catholic masses in the all-white- and-gold marble chapel one Friday a month and every religious saintly holiday. To nuns who never let uneaten food from home be thrown away at lunch. (I ended up finding a lone trash can outside the building where I’d dump my mother’s at-times-revolting sandwiches like sardines on white bread. The horror.)

“Yes, she’s doing very well in all her subjects.” Sister Rachel smiled. I beamed at my mother. The year before, in third grade, a parent-teacher conference meant a teardown. My grades were top-notch, but I was constantly in trouble for talking too much and not focusing. Attention deficit was to blame, and I was bored. Mom caught on and instead of punishing me, stood up for me. She told the teacher that I needed to be challenged so I was let loose into books and workbooks from the next grade up, as advanced as I could take. That helped quiet me down, a bit.

“That’s so great to hear,” my mother said as she put her hand on my shoulder after she was told I was a straight-A student yet again.

“She must get it from her Chinese side,” said Sister Rachel.

My ears perked up.

Mom just smiled and said, “Sure.”

I stood in shocked silence.

Yes, I was a Wong, but Papi wasn’t the one there to make sure my homework was done. He wasn’t going to parent-teacher conferences. I don’t even know if he knew where I was going to school. But Lupe was there. Always pushing, always expecting. The tiger mom of lore but Caribbean born, not the Asian parent. And Sister Rachel thought it was okay to give Chinese genetics credit instead of the mother standing before her? So, Chinese people were “smart.” But brown and Black people were not, and in my teacher’s eyes maybe could not ever be.

On the car ride home, I was nervous to ask but I had to: “Mami. Sister Rachel said I’m smart because I’m Chinese.”

“Mm-hmm.” Mami looked straight ahead at the road. She said nothing, but her face communicated a script I couldn’t fully decipher. What I was able to glean from her expression and lack of words was that my mother wasn’t telling me something in particular. She hinted at it with a sly smile. But it wasn’t the Mona Lisa I was looking at. She was more like a Cheshire Cat. In her mouth she held something secret. Her face amused by something she was holding back. It was a rare countenance for her to have. As rare as the truth of what she was concealing.

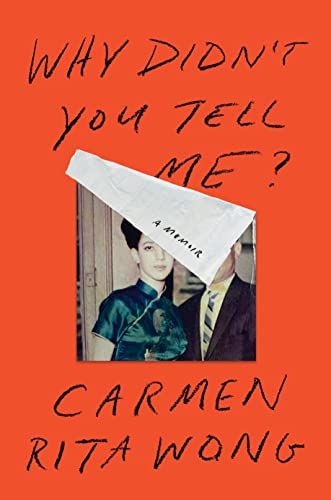

From the book WHY DIDN’T YOU TELL ME? by Carmen Rita Wong. Copyright © 2022 by Carmen Rita Wong. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io