First I made borscht. I yanked the skin off chicken drumsticks. I hovered over the pot like an anxious parent at the playground, spooning off froth. I sliced cabbage into ribbons and grated beets until my fingertips were magenta and raw. Consulting notes scrawled on Post-Its, I tried to divine what my mother meant when she said the water should be “warm but not hot”—that way the beets would keep their color. Topped with yogurt (in lieu of sour cream) and fresh dill, the result was close but too watery.

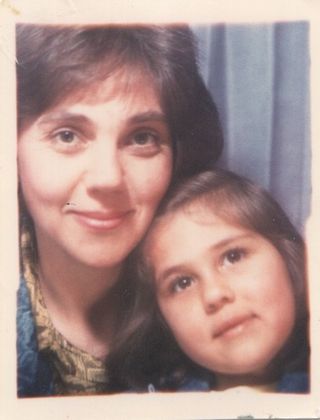

Until that Sunday in March, I had never tried to make the soup I ate growing up, or virtually any of my mom’s recipes. As a kid, I found her dishes comforting but banal. We mostly ate a revolving menu of staples she brought with her from Kiev—beets and mayonnaise were in heavy rotation. My mom immigrated to the United States with a 4-year-old daughter and her own mother nearing 80. Trained as a classical music historian, she found work as a translator and then an administrative assistant, occasionally bussing tables at parties for extra cash. As dementia clouded my grandmother’s mind, my mom delivered home-cooked meals to her senior home every few days. She got up an hour early to pack me challah sandwiches and cooked almost every dinner from scratch. But she didn’t have much time or money to experiment in the kitchen.

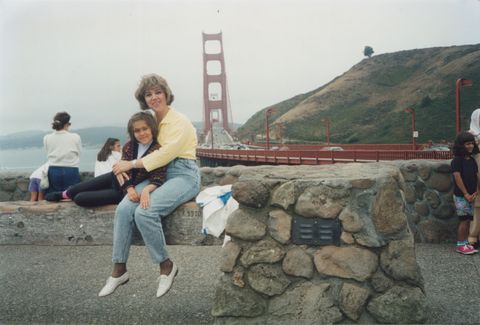

In the outer boroughs of San Francisco, where we lived, I found the cuisine outside our home more exciting. In middle school, my friends and I stopped for steamed pork buns and bubble tea after class. In high school, we went out for shrimp burritos or dolmas or unagi rolls. When my mom and I briefly moved in with her coworker so I could have my own room, I pined for the exotic (and expensive) foods she served at dinner parties: kabocha squash and wild rice and orange flowers you could eat in salads. As I started learning to cook in my thirties, I still preferred the unfamiliar: salmon with za’atar, soba with plum sauce, Indian dal.

In early March, as the pandemic raced through the country unbridled, my husband and I stocked up on ingredients for kale and chickpea minestrone and Persian beef stew. Then I got a call from my Mom, now 71. She’d heard on the news that a fellow passenger on her recent cruise to Mexico had been one of the first Americans to die of coronavirus. Her quarantine began two weeks before the Bay Area became the first place in the country to shut down. Like so many other families during this pandemic, we disappeared from each other’s lives overnight—reduced to masked apparitions, disembodied voices, pixels on screens.

As isolation set in, instead of pad see ew or injera, I craved the uncomplicated warmth of my Mother’s borscht. She could no longer continue her near-weekly ritual of sending me home with leftovers in old honey jars or sour cream containers. I realized, with a pang of regret, that I had no idea how to recreate the dishes I’d taken for granted.

So I started calling to ask for her recipes. After borscht, she walked me through sautéed cabbage and carrots in tomato sauce, which I served with Trader Joe’s sausages instead of the plump ones in papery casing from the Russian deli. Next I tried turkey kotleti, thickening the ground meat with pulped potatoes and shaping it into ovals. They were pillowy like my mom’s but stuck to the pan.

I moved on to a salad of red cabbage, carrots, and green apples, wondering how she had the stamina for so much grating. Then I tossed celery root with green apples, garlic, and blanched peas, a dish my Mom served on the summer pilgrimages she scrimped for all year, to a shared cabin on a lake outside Yosemite. After that, I mixed a salad of roasted beets with garlic and cilantro, which she always brings over on Thanksgiving. Each dish called for a dollop of mayo or sour cream and some fresh herbs. Before I knew it, months of social distancing had turned into a mother-daughter correspondence course in home cooking.

For the first time, I saw how much my native cuisine relies on the resilient vegetables we’ve been urged to stock, the ones that got my Ukrainian-Jewish ancestors through harsh winters, famines, pogroms, and Stalinism. Growing up in Kiev, my mom told me over the phone, she’d stand in line for hours to receive rations of sugar or eggs. Sometimes she’d walk into her neighborhood deli to find nothing but tomato juice or marinated pickles on the shelves. After the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, when I was one, she had a friend’s relatives ship condensed milk from other Soviet states to avoid exposing me to radiation in local dairy products. My mother’s mother fled a village in Eastern Ukraine in the early 1930s, at the onset of a man-made famine that killed millions, after the leader of her communist youth group warned that her flesh might look too appetizing to the locals. Later, she escaped Kiev with her four-year-old son just before Nazi forces massacred nearly 34,000 Jews over two days in a ravine at the city’s edge. My mother’s dishes carried stories of suffering, but also of survival.

Two weeks after my mom returned from her cruise, she still wasn’t coughing or feverish. A couple friends she’d hugged on board got sick after they landed, but both tested negative for coronavirus. I felt relieved and fortunate. But as the quarantine stretched from weeks into months, my fear simmered. As the world fitfully reopens, even as cases surge in California, it’s approaching a boil.

Since the beginning, I’ve shopped for my mom’s groceries and insisted we meet outside, six feet apart. I’ve delivered face masks and policed her hand-washing habits. But she is bored and craves her independence. A few weeks into quarantine, she regularly began asking if she could shop at the farmer’s market or get away for the weekend or, for some reason, buy a tricycle.

“Not yet,” I would say.

“It’s like our roles are reversed,” she joked.

By July, when I was attempting my mom’s breaded cauliflower recipe, I realized she had begun asking for forgiveness rather than permission. Bread and fresh produce dropped off her weekly shopping list, and she confessed she and her 84-year-old partner had begun going to the bakery, the local produce shop, and the farmer’s market. They started eating takeout with friends in the park—at a distance, she claimed.

Then, a couple weeks ago, we got into an argument. “Our friends are in their 80s, and the whole family came over to their apartment for a birthday dinner, no masks in sight,” she said. Other friends had posted Facebook photos of extended family get-togethers. She questioned whether my response to the virus had veered into “hysteria.”

I lost my temper. “They’re idiots! If they want to ignore science and put their family in danger, that’s their problem.”

“What kind of life is it when you can’t be physically close? Maybe relationships aren’t worth a grosch to you,” she said, using the Ukrainian slang for “penny.”

That stung. It was torture not to hug my mom, and keeping her and her partner healthy was the reason I was being careful. But in the absence of a national shared reality about the facts of the virus, some complain of skin hunger and wave to grandkids through windows, while others party indoors as if nothing is going on. We are all gaslighting each other. And it’s the virus that doesn’t give a grosch.

When we made up a few days later, my mom agreed to do her best to follow the rules. “I’m doing it for you,” she said.

As I called my mom yet again recently, this time for her chicken stew recipe, I realized this was about more than comfort cooking. Being isolated from our loved ones can feel like a trial run for a permanent separation, for the inevitable. Until now, it was easier to engage in magical thinking, to act as if the limits on human life didn’t apply in her case. I can barely linger on the thought, but it’s getting harder to ignore: I’m ultimately powerless to keep her safe.

During these days turned upside down, mastering my mother’s recipes has helped me feel closer to her from a distance, and to stomach the low hum of grief we all now live with. I recently started bringing her stuffed cabbage and pickle soup home with me again, but one day I will have to make these dishes without her help. Someday I will pass them on to my own children. For now, I call her and try to get it all down.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io