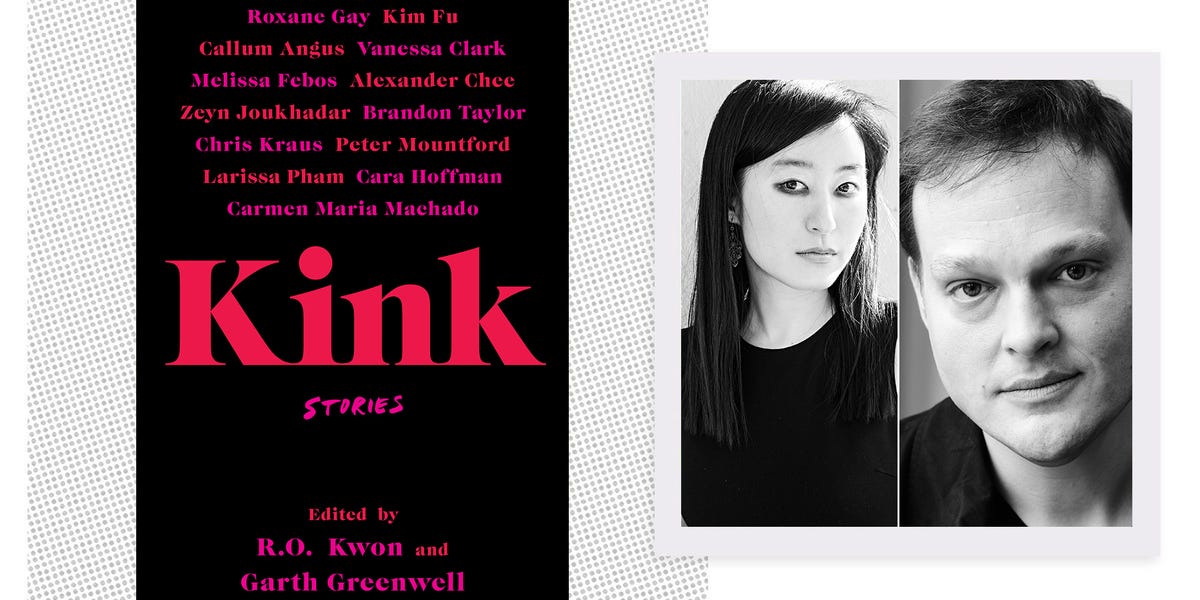

S&M is like “commedia dell’arte: a stock repertoire of stories, bits, lines, and gags,” muses writer Chris Kraus. Kraus’s short story (“Emotional Technologies”) is one of 15 in the recent anthology Kink, published earlier this year, which thoroughly explores the sexual practice. Suffice it to say, it’s pretty much the perfect companion for Hot Girl Summer. Here’s why: The joint editors—R.O. Kwon, author of The Incendiaries, and Garth Greenwell, author of What Belongs to You and Cleanness—compiled an array of voices, styles, and experiences to explore this charged psychological-sexual terrain without lionizing or criticizing it. Experiences are heightened and expectations are distorted, touching on risk, gratification, indiscretion, discovery, indulgence, discomfort, boundaries, and taboo. Ultimately—as stated in the acknowledgments—the collection is addressed, “To everyone who’s ever felt out of place because of what your body wanted.”

ELLE.com spoke to the co-editors—located in the Midwest and on the West Coast, respectively—via Zoom to discuss battling TERFS, being deprived of “the sex talk,” and refusing to soften the flaws of kink experiences.

How did you become collaborators on this anthology?

R.O. Kwon: I first got to know Garth because I interviewed him upon the publication of What Belongs to You. I’d also heard him read in San Francisco. What he said was so beautiful and so eloquent and I believed in it so much—it felt like literature church. It was just like: “AMEN! To all of this!” [Laughs]

I approached Garth to work on this book with me in part because I really love his writing, in part because I really love the way he thought about the place of sex in literature. I emailed him, and much to my delight, he was up for it.

The idea for the anthology came about in 2017. How did things evolve thereafter?

Kwon: Since the book was conceived, kink is more of a topic of discussion. That said, there is still a lot of ignorance. I was steeling myself for it. But ignorance is never not a surprise to me, no matter how much I’ve prepared. We spent some of our time pushing back against that ignorance.

How are people communicating this ignorance—is it all online trolling? And what does pushing back look like, exactly?

Kwon: There’s an entire strain of people who conflate kink with abuse. I find it to be both ludicrous and exhausting. Kink has nothing more to do with abuse than sex has to do with assault. Abuse happens; assault happens. That doesn’t mean sex is assault; it doesn’t mean kink is abuse. To push back against it… What did we do, Garth? [Laughs] We’ve written some pieces.

Garth Greenwell: I was not shocked that there was ignorance and prejudice around kink, or by the overlap between anti-kink rhetoric and homophobic rhetoric. But in the U.K., there is this astonishingly loud and incoherent anti-trans discourse right now, and anti-kink rhetoric was coming from the same people. Someone would be yelling “kink is abuse!” on Twitter, and you go to their timeline, and all of their other tweets are about quote unquote men wanting to abuse women in bathrooms. Or quote unquote women who have internalized misogyny to such an extent that they want to erase womanhood—these really horrifying anti-trans standard arguments. I found that overlap curious and, in a horrible way, fascinating. To realize these are people who have—as a central occupation of their lives—the desire to tell others what their bodies mean, and what the things that they do with their bodies mean: “Oh, what you are calling intimacy, or play, or theater, is actually abuse.” What is really at stake is the question of autonomy, and who gets to determine what my body and my desires mean. That was a surprise to me—the extent to which the TERF rhetoric overlapped with anti-kink rhetoric. I hadn’t anticipated that.

Several of the stories express the inability of language to articulate specific desire. There’s an almost locked-in sense of something that’s impossible to verbalize. As writers, how do you wrestle with that failure of language—even as it is, of course, your tool?

Greenwell: I think that’s true about desire—but I think that’s true about many things. The whole reason I write is that I feel there are resources that literature offers. The pressure of syntax, and the shapes that sentences can take; those provide tools for thinking that I don’t have in everyday language. I think that’s why we sit and wrestle with a sentence for eight hours—because we’re trying to use some of those extra semantic resources that art allows us to access in language, to pack in more meaning than everyday casual discourse allows us to.

In Alexander Chee’s story (“Best Friendster Date Ever”), the main character says: “It’s good to be wary of people who are afraid of what they desire.” Melissa Febos writes the antithesis of that in her story (“The Cure”), with her character saying: “It is difficult to gauge one’s own desire when one is calibrated to the desires of others.” Although opposite opinions, both sentiments are understandable! There are those who know they want to be experimental, and those who have been so pressured by cultural normativity they’ve silenced their desires. What are your thoughts?

Kwon: There are difficulties that arise the minute anyone starts wanting anything—how complicated things can be when we want something for our bodies! I don’t think it’s controversial to say that the more marginalized you are, the harder it will be to claim those desires. For some people, it’s a lifelong project. People must think that, because Garth and I put out this book, we are free. I don’t feel free. I feel so wrapped up in confusion and shame with things having to do with my body. But I’m working through it, and it is a project of mine to work through it, and it is possible.

I didn’t grow up in a house where anyone ever talked about sex. This “sex talk” that people get? This does not apply to Korean women. [Laughs] We did not get talks. My sex talk was… I was not allowed to go to sleepovers. Good Korean girls didn’t sleep at other people’s houses. I missed out on all that bonding—I’m still hung up on this. Do you know how hard it is to be an American girl and not go to sleepovers?! It was fucked up! That was my sex education. I didn’t kiss anyone until college. No—I kissed one person when I was 11; his name was Elliott. It was at a two-week geek camp that you test into and are around people who love books as much as you do—for once in your life—and it’s glorious; then you go back home.

I just want to say for anyone who feels unfree: It’s not a binary. It’s not like you’re free or you’re unfree. It’s not like you get what you want or you don’t get what you want. And if you do feel unfree… maybe you can get a little freer. But also, if you can’t… it’s a hard thing. I don’t want people to beat themselves up about what they can and can’t claim about what they can and cannot do for themselves. Life is hard.

Greenwell: To me, the fact that both of those quotes feel true to us points to just how complicated these questions are. Which is why we need art to think about them.

What Reese said sounds familiar to me—I also never got a sex talk! My mother, a Southern woman, was not going to tell me anything about sex. I also went to a camp for kids who scored well on standardized tests—it was at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green, Kentucky. I was in 7th grade. And in the Student Center, there was a cruising bathroom. I didn’t know what that was, but it was covered in graffiti, like pre-Internet personals and sex ads. My mind was blown. It was a revelation to me that this world existed. From that point on, I was constantly looking for it. Cruising gave me a sexual education, but it was also an education in sociality itself. It was in cruising parks in Kentucky that I met people who my entire life was organized around to keep me from meeting. And then, all through my life, cruising—and certain kinds of sexual communities—have been central to how I’ve experienced the world. I feel really grateful for that.

Are there certain aspects of the story collection that you wish were more frequently discussed?

Greenwell: We’re so proud of the diversity of the anthology—diversity conceived along the lines of identity, along the lines of sexual practices—but we’re also really proud of the aesthetic diversity of the anthology. We have straight realism, deep psychological writing, an auto-fictional essayistic story, grand macabre historical fiction… I think that people have not talked enough about the art in the book. And I understand—the subject matter is obviously attention-getting, and it is an anthology organized around subject matter. But we weren’t just thinking about subject matter; we were thinking about form and style, and how these stories were working as art.

Kwon: Some people have been yelling: This isn’t erotica! Why are so many of these people sad?! I feel a little bad for people who picked this up expecting a certain kind of experience.

Greenwell: Some people have been upset that several of these stories are quite dark and interested in exploring aspects of kink that are not what you put on the poster to mainstream it or say, “Look how bright and happy everyone who engages in kink is!” We don’t do that. Some stories have sweetness and humor. But there are stories like mine, where an encounter goes really wrong. There’s been a lot of upset that that is not how we should be portraying kink. Anyone who has written from a minority experience has heard this, including me: “Why can’t you write gay characters who are happy and well-adjusted?” Well, I’m interested in fiction where people make bad choices! [Laughs] That is narratively more interesting. It’s not a self-help book. It’s not a how-to book.

I mean, a “bright and happy” version of anything is basically just propaganda. Who wants that?

Kwon: It’s a form of violence, honestly, to demand that people represent a part of their experience that has been marginalized in a shiny, happy way, so that people don’t look bad. It’s so foreign to my notion of what books are. I think it’s actually really disrespectful. If I only ever wrote about Koreans in a positive way, I would be an advertiser; I wouldn’t be a writer. The writers I love are interested in digging really deep—in seeing people. I wouldn’t want to read otherwise.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io