The artist wants to transport people with his scents, not keep them stuck in a binary way of thinking about gender and perfume.

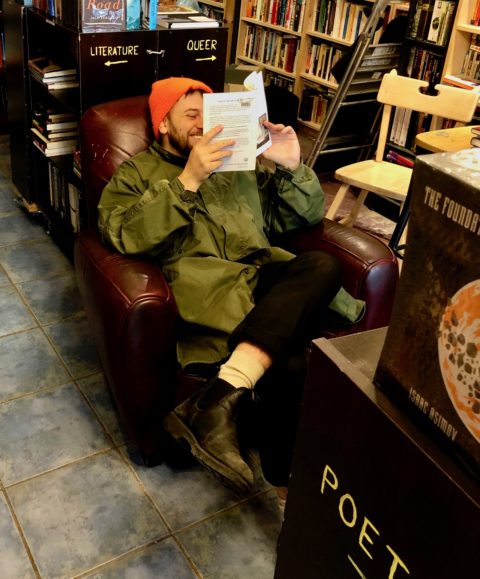

When the world ground to a halt in the spring of 2020, writer, director and dramaturg David Bernstein was faced with a stark new reality: he was a theatre-maker in a world without any theatres.

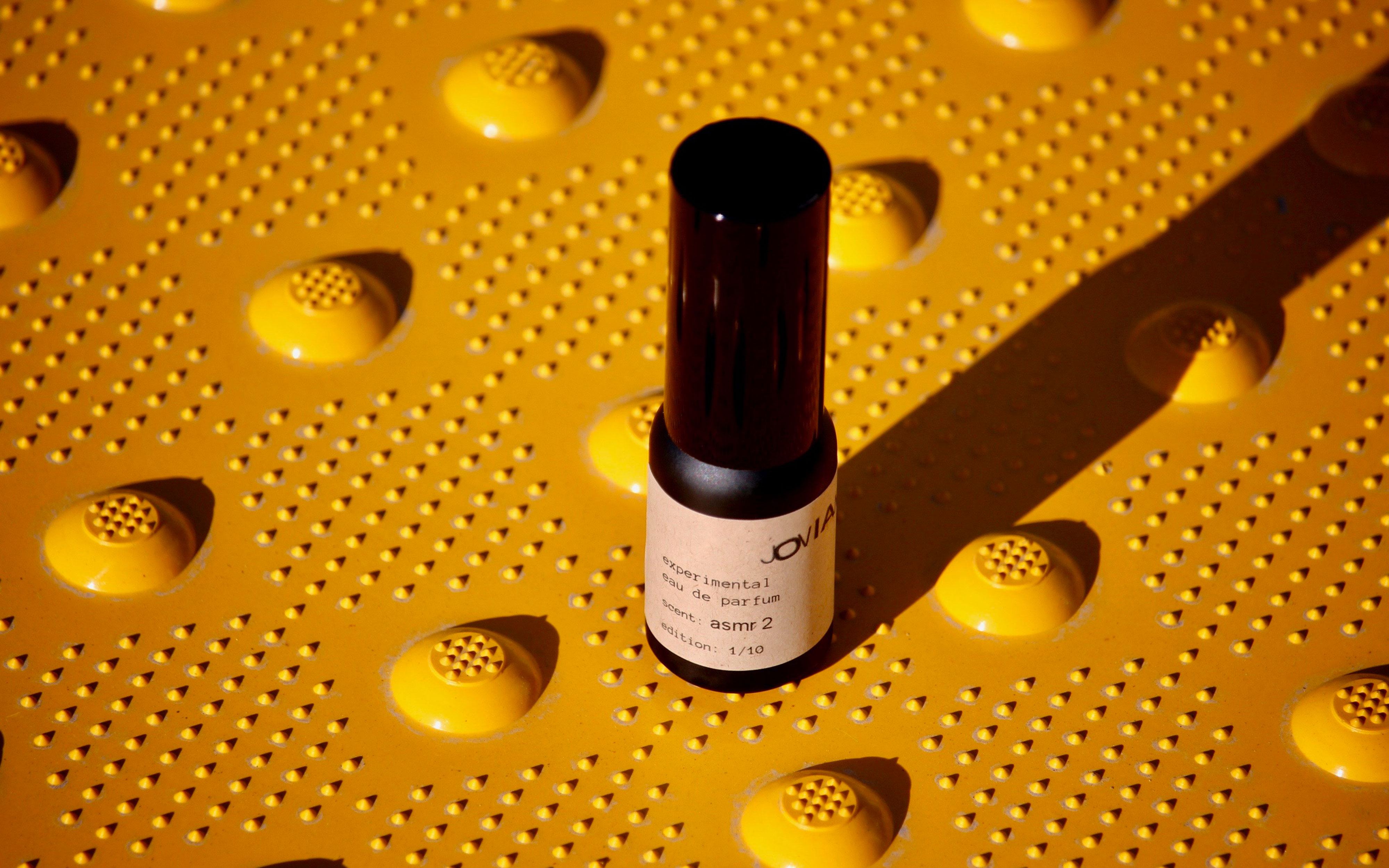

As others in the theatre industry were contemplating virtual performances and digital media, Bernstein began to explore another of his longtime fascinations — scent. The resulting company, Jovian, is a scent art studio based in Toronto that produces what Bernstein describes as “psychoactive perfume for skin and space.” The small batch, hand-crafted scents are a mix of aromatherapy, traditional perfuming, and playful nods to new age philosophies and drug culture — Jovian offers scents in “uppers” and “downers” and employs an in-house astrologer, Jaime Wright, who helps dictate the formulas.

As a gay man, Bernstein has taken a queer approach to the heteronormative field of scent, an industry so gendered that it splits its offering in two straight across the gender binary; colognes for men, perfumes for women. Jovian’s all-gender scents are certainly not the first offerings to eschew the perfume binary, but they’re particularly innovative because they don’t just toss away the old binary labels for scents, but also the gendered associations with particular ingredients.

The decision to go all-gender was informed by Bernstein’s days selling perfume at a department store to support himself while he was a student at New York University’s TISCH School of the Arts. In that position, Bernstein says he was constantly met with customers’ deeply held beliefs about scent and gender. “It’s amazing, “ he says, “when you’ve worked as long as I have in perfume, people’s gender hang ups come right to the forefront.”

Customers, Bernstein says, would be intrigued by scents he’d introduce them to, but shoot them down because of their gender. “They’d say, ‘Oh, I love it, but is it too feminine?’ or ‘Is it too masculine?’”

“It doesn’t have genitals and it doesn’t have a socially defined gender performance,” he says in response to that line of thinking. “No, it’s not too feminine. It’s liquid.”

Around the same time, Bernstein discovered CB I Hate Perfume, a brand that takes inspiration for its scents from unusual sources that span from snow to dust to sushi. The boutique quickly became one of his favourite places in New York City and the brand’s philosophy eventually helped inform Bernstein’s own take on scent. When he started Jovian, Bernstein embraced a queer fluidity as he sourced ingredients, exploring how different ingredients mixed together to create an emotional state rather than the age-old perfume ideology of how they’d help the wearer attract suitors of the opposite gender. He also embraced his own mix of uncommon materials like fresh hops, porcini, ginger lily, and coffee.

The idea behind each Jovian scent is to transport the person who smells it, ultimately allowing it to change their state of mind. The approach is informed by Bernstein’s work in theatre as a “scent designer” — an artist who creates scents to be released into a theatre space in hopes of transporting the audience. If, for example, a scene is set in an orchard, a scent designer might create a mixture evoking trees and fruit that would be diffused during that moment in the play, kind of like an artistic take on smell-o-vision. The same method is occasionally taken with fashion, like when Alexander McQueen tapped Bernstein to create three custom scent effects for a dance-based presentation of its McQ wares at the New Museum.

As a queer creative and business person, Bernstein says he’s spent this Pride Month reflecting on who space is held for in the LGBTQ+ community — particularly those whose identities are afforded less privilege than his own as a gay white man. This year Pride Month also intersected with some deeply troubling events that have been on Bernstein’s mind, including the revelation of hundreds of unmarked graves at the sites of residential schools across the country. Beyond the human level, Bernstein says he’s been reflecting on being in a business that extracts natural materials from the land given Canada’s fraught relationship with land and its original caretakers.

“The oils have been sublimated from agricultural product to liquid extraction, the bottles have been made in a factory, and all have been shipped across borders and socioeconomic contexts,” Bernstein explains. “So, a lot of conceptually and ethically profound things have happened before I even blend the first drop of scent.”

About half of the essential oils he uses are sourced from India, which is currently dealing with a devastating surge of COVID-19. “My queer utopia of scent functions on labour from elsewhere — that’s something I’m staying mindful of,” he says, explaining he’s shared fundraising efforts from relief organizations in India on the Jovian Instagram and made donations on behalf of the company, but he’s looking to go beyond short-term, reactive responses. “To me, queering a particular discipline means, in part, trying to work from the collisions and tensions contained within it,” says Bernstein.

“I want to find ways of moving beyond my own visions, impulses and contexts as a ‘queer artist,’ and apply the same irreverent, subversive lens to queering the ethics of production.”