On October 21, 1966, a coal tip flooded by heavy rains collapsed in Aberfan, Wales, engulfing parts of the village, including the Pantglas Junior School, and killing 116 children and 28 adults. The disaster was dramatized for the first time onscreen in the third season of The Crown; the episode, titled “Aberfan,” details the day leading up to the tragedy and its aftermath, as the town’s surviving inhabitants dig through the rubble and eventually receive a visit from Queen Elizabeth (Olivia Colman). It’s a harrowing and palpably realistic hour of TV, existing almost as a stand-alone film in its intensity and unusual plot structure. It’s no surprise, then, that many of the series crew are nominated for an Emmy for the episode.

“This stepped way outside The Crown’s comfort zone,” explains Martin Childs, the show’s production designer, who is nominated for Outstanding Production Design for a Narrative Period or Fantasy Program. “This is something happening massively somewhere other than one of the palaces. It’s a story that really needed telling. It would be completely wrong to call it a breath of fresh air, but it was a breath of some air that gave the audience something to look at other than what they are used to.”

“There’s something so valuable in this episode,” adds costume designer Amy Roberts. “Doing a miner or a miner’s wife well is as important as doing the queen well. And, actually, as interesting.”

Childs, Roberts and cinematographer Adriano Goldman tell ELLE.com about the detail, responsibility and emotion involved with pulling off “Aberfan.”

Reimaging Aberfan in 1966

Childs and his team compiled about 40 sets for the “Aberfan” episode, including the village itself. Instead of filming in the actual town of Aberfan, production traveled to Cwmaman, a former coal mining town in the heart of Wales. They used existing rows of homes, and the team turned the house facades back to their ‘60s iterations by repainting doors, replacing windows, and modifying anything that looked too modern. They also altered any visible interiors, adding in drapes and painting walls. All modifications were supported by town’s current inhabitants, who wanted to see the story told. The subtle pops of red throughout the village, which echo the queen’s brick-colored ensemble, were purposeful.

“I very much wanted it to be the colors of the earth,” Childs notes. “I wanted the village of Aberfan to be something part of nature and part of the earth, and then this dreadful thing happens to it. It’s a way of contrasting with the royal household and the palaces.”

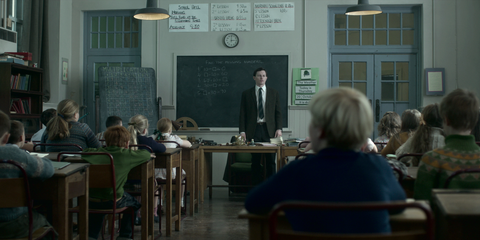

The schoolhouse was built twice, once around an existing structure in Cwmaman and then as a destroyed version at London’s Elstree Studios. Childs copied real items from the Pantglas Junior School classroom, including the desks, from photographs documenting the objects dug out of the rubble.

“People walked into that schoolroom after we’d dressed it and said, ‘This takes me back to the 1960s,’ Childs says. “It’s all in the detail. The biggest challenge was respecting the memory of the people who had lived through this and the memory of those who had died.”

The inhabitants of the town, many of whom were played by Welsh locals, also needed to feel authentic to the time and place. Roberts focused on clothes from the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, rather than 1966, because not everyone would’ve owned something current. The colors are muted to reflect the weather and somber tone, with many of the pieces un-ironed or folded with haphazard creases.

“I didn’t want them to think they were costumes for a second,” explains Roberts. “Everybody felt that we had to be massively respectful, more than anything.” She continues, “It’s difficult when you do a fitting and think, ‘Those trousers look a bit short’ or ‘That jacket looks a bit big.’ You stop yourself going in to correct that, because people look like that, don’t they? People buy off the peg and they’re not going to take the trousers up or let them down. They’ve got better things to do.”

Digging through the ruins

The disaster itself was rendered onscreen with a combination of practical shots and VFX. Filming the citizens of Aberfan as they dug through the black mud and ruins of buildings in search of their loved ones was intense and challenging. Childs built the rubble on the backlot of Elstree Studios, partially due to logistical concerns and partly because it would’ve been in bad taste to physically replicate the tragedy so close to Aberfan. While some of the debris and dirt is real, most of the ruined town set was built and faked using a skeleton framework with layers of dirt and detritus.

“I learned from my days on Shakespeare In Love, when I thought it would be fun to have real dirt on the floor of the Globe Theatre,” Childs recalls. “What I didn’t realize was that under the studio lights, all the bugs that lived in the dirt would come alive. As soon as Joseph Fiennes started having his legs bitten during rehearsal, I realized, ‘We have to fake it a bit.’ You do learn on the job that no matter how much you want things to be absolutely real, it’s better to have some decent fakery involved.”

Ahead of filming, Goldman met with Nigel Walters, a former BBC Film cameraman who was one of the first to arrive in Aberfan the night of the disaster. “He told me the most disturbing thing was the silence,” Goldman notes. “It was absolutely quiet so you can hear the survivors if they’re knocking on something or trying to get the attention of the rescuers.”

Goldman and director Benjamin Caron wanted to echo that emotion in the visuals. They used minimal lighting and brought in fog so the people of Aberfan appear mostly in silhouette. In reality, the town had lost its electricity, so all the light came from the rescue teams, fire department, and flashlights.

“It’s a realistic approach, to be honest, and it makes it so sad,” explains Goldman. “They’re all parents, the rescuers, on the same emotional stage, and it didn’t make much sense to us to actually identify each of them. They become ghosts searching for the kids and that felt to us like a very strong image. It was also playing with this black-and-white environment where all the color is gone because the kids are dead.”

Remembering the victims

Following the tragedy, the town of Aberfan held a memorial service for those who died. In the episode, it’s attended by Prince Philip (Tobias Menzies), although in real life, he wasn’t actually present for the service (he visited with the queen later). To recreate the stark drama of the moment, the production design team built several child-sized coffins, which were laid out in a grave they dug into the field. VFX extended the shots of the coffins and the crowd to make them larger in scale, with the camera pulling out in a drone shot to reveal the coffins arranged in a cross.

“It’s a painful thing to do, but nothing like the pain people suffered in real life,” Childs says of constructing the coffins. “It was our responsibility to get that right, so yes, we built the grave and yes, we built the coffins. The emotional response to a child-sized coffin is quite something.”

“It was a very, very emotional day,” Goldman adds. “The preacher’s speech is so moving and he’s [Hugh Thomas] such a lovely actor in the way he delivered the words. All the extras were actually crying. The extras were mainly from Wales, so it was a story they all knew. They really understood the story and felt it on the day.”

For Roberts, it was important to showcase real people, rather than focus on the palace and royal family. She wanted to keep things authentic without being too costume-y or making the crowd look downtrodden, especially in a moment of remembrance. “It’s a Welsh mining village and it’s poor, but it’s not raggedy,” she notes. “It’s not Dickens. These are proud working people.”

The Queen (finally) arrives

When the queen first hears the news of the Aberfan disaster in the episode, she’s sitting at her desk in the palace, dressed in a floral pink blouse. That look was intentional for Roberts, who wanted to contrast the reality of the harrowing scene in Wales with the queen’s inability to take action.

“There’s a journey for her through that story,” Roberts explains. “She doesn’t know she’s going to get bad news and I liked the sense that she’s clean and pretty and motherly. And Margaret, when she receives the news, has come in from a party in a glittery dress and a fur coat. That’s life, isn’t it? Events happen and you don’t know they’re happening. They’re wearing something quite inappropriate.”

She adds, “The colors are soft, feminine, motherly—and yet those are all the things she can’t be. When Wilson is trying to persuade her that it would be a good move to go there, she’s wearing that Madonna blue, a comforting color, and yet that’s the one thing she can’t be. And she knows it.”

The queen finally agrees to visit Aberfan, and Roberts wanted to recreate the brick-red coat and fur-lined hat the real queen wore to the exact detail. “The Crown DNA is a balance,” she says. “It’s a balance of getting real moments and key moments, like the queen in Aberfan, like the Silver Jubilee, right. The classic ceremonies people will probably know or remember or can easily reference and events that are absolutely recorded, you have to do that. Then there’s so much in between where you don’t know what goes on and you can do flights of fancy. I don’t know if I have thought of using brick red, and I think it’s quite startling in, hopefully, a good way.”

Throughout the episode, the queen often appears in silhouette from behind—a visual trademark of The Crown. “Aberfan” ends as the camera moves up from behind the queen to a close-up shot of her face as a single tear finally trickles down her cheek. It’s the only time in the episode she shows real emotion, and the camerawork in the episode reflects that.

“Those [silhouette] shots are very much part of the visual grammar of the show,” Goldman explains. “But also, it made total sense to do more of those shots from behind on the ‘Aberfan’ episode because she’s in deep conflict. She cannot show emotion, she never cries—and she’s very open to the Prime Minister saying that. Shooting her from behind puts us with her and makes us share her anxiety and internal conflict.”

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io