This article was originally published in January 2019.

About a year into my first real job, as a junior editor at Toronto Life, I arrived at my performance review — a breakfast meeting scheduled for 9 a.m. — 25 minutes late. I’d been wild with nerves the night before and couldn’t sleep. At 4 a.m., I made the decision — the kind of decision you make at 4 a.m. — to pop a trusty tranq. I was in my mid-20s and deep into an Imovane phase — my blue period. (For the blissfully uninitiated, the tablets are Smurf blue.) I recall arriving at the restaurant to meet my boss with about as much grace and limb control as Molly Ringwald’s older sister, Ginny, in Sixteen Candles — in that scene when Ginny staggers down the aisle on muscle relaxants.

This was hardly my first nuit blanche. Even when I was a child, the prospect of a sleepover roused in me an unholy dread. I’d lie there fantasizing about things like fainting and the first flush of dawn while my friends fell, with infuriating immediacy, into the deepest slumber. I proceeded to go through much of high school and university popping a great variety of over-the-counter sleep aids like Skittles. Many years have passed since those days, and I (blessedly) struggle less with insomnia than I once did. I have a toddler now, and one of the secret upsides to being a brand-new parent is, as far as I can tell, a kind of advanced level of mind-blunting exhaustion that got rid of my insomnia: In that first postpartum year, I basically went from being an insomniac to a narcoleptic, expertly dropping into short comas more often than most soap opera characters.

Unfortunately, I have not definitively put the problem to bed. Whenever I feel anxious or nervous, I tend to stop sleeping. A few months ago I turned 40, and I was visited by a fresh bout of insomnia. In fact, this official passage into middle age felt something like staying up until 4 a.m. — a realization that I had only so much time left and that the quality time might be behind me. I’d lie awake, stricken by my hyperactive tag team of worries (professional, financial, familial, etc.), while my son, Leo, slept soundly in his crib. Friends of mine asked me, vis-à-vis his REM habits, if I had “sleep trained” him. And I realized that Leo doesn’t need sleep training; I do. So, by the way, does my husband. There are different kinds of insomniacs — including those who have trouble falling asleep (me) and those who wake up in the middle of the night and have trouble falling back to sleep (husband). We are sleep-crossed. It now occurs to me that in our early candlelit dating days, I should have asked him “So, what kind of insomniac are you?”

We are not alone in our respective sleep issues. At least 30 percent of Americans are sleep deprived, and 15 percent are getting less than five hours a night. (Most adults need between seven and eight hours.) In Canada, nearly two-thirds of adults report feeling tired “most of the time.” Arianna Huffington’s book The Sleep Revolution explores (in exhaustive detail) how we, as a culture, are in the throes of a sleep crisis but are too disordered to acknowledge it. Huffington, by the way, was inspired to write the book after collapsing from burnout at her desk and breaking her cheekbone. As a civilization held in thrall to ideals of productivity and stamina, we devalue sleep, deeming rest the indulgent hobby of the weak. But, Huffington argues, if we can rehabilitate our relationship with sleep (as in, get more of it) we can improve our lives, be more successful and discover joy. We can also, evidently, be smarter — or, if not smarter, then less stupid.

If we’re in the midst of an epidemic of exhaustion, we might also be on some kind of zombie walk toward an “age of idiocy.” As published by the American Academy of Neurology, researchers discovered that persistent sleep deprivation is associated with a decline in brain volume. A 2014 study from Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School established that the less we sleep as we grow older, the faster our brains age. A lack of sleep can lead to an irrevocable (irrevocable!) loss of brain cells. So, if I feel stupider now than I did 10 years ago, it’s because I am.

One piece of advice I encounter is to analyze my sleep environment. I take this advice quite literally and retire my springy, overtired mattress in favour of a new one, specifically a Casper. “As humans, we’ve been trained to think about sleep as something we have to do, as opposed to something we want to do,” says Neil Parikh, chief operating officer for Casper. Parikh, whose father was a sleep doctor and who has the clear, bouncy voice of the well rested, continues “When we were kids, what was the punishment our parents gave us? It was often ‘Go to your room! Go to sleep early!’ So, since childhood, it has been rooted in our psyche that sleep is a negative thing.” But we don’t need to follow the rigid latteless, wineless (and generally joyless) prescription of yore to excel at sleep. “When there are too many rules, you say to yourself ‘This is too difficult; I give up!’ he says. “It’s the 80/20 rule. There are high-yield things that would make a huge difference.” And the Casper does make a big difference. It manages “motion transfer,” which means that when my husband gets up in the night, I no longer feel like the boy in Life of Pi, clinging to the edge of a raft.

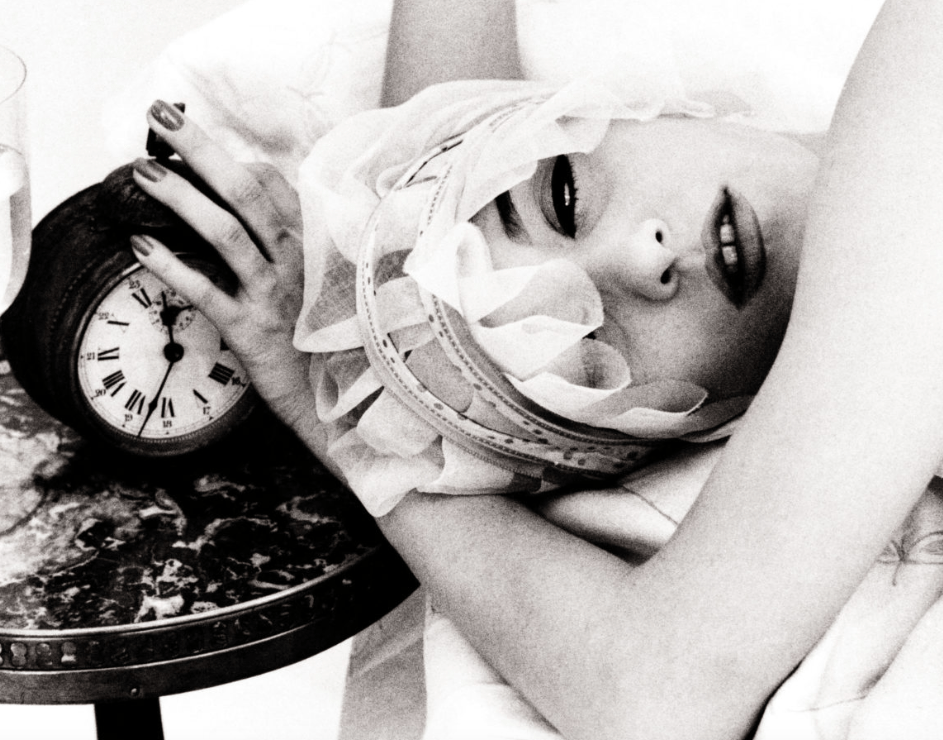

I also seek the counsel of a sleep doctor and catch a repulsively early flight to New York to speak with Dr. Rebecca Robbins about the need to prioritize sleep. Robbins, of NYU’s School of Medicine and co-author of Sleep for Success: Everything You Wanted to Know About Sleep But Were Too Tired to Ask, tells me that consistency is the cornerstone of good sleep and that I should go to bed and wake up at the same time every day (even on weekends). Imposing this kind of routine can be challenging with a toddler, however, as Leo is my alarm clock. Robbins also orders me to turn off all electronics before bed. (Basking in the blue light of our smartphones suppresses the release of sleep-inducing melatonin, tricking our minds into thinking it’s daytime.) She also extols the soporific, therapeutic delights of engaging in pre-bed rituals, like applying a fragrant sleep mask.

I follow doctor’s orders. I apply Amorepacific’s Time Response Skin Renewal Sleeping Masque, which is scented with a rest-inducing cocktail of neroli, rose, ylang-ylang, sandalwood and bergamot. (If I don’t wake up rested, at least I will look the part.) And while my phone is enjoying a full night’s sleep in the other room (I adopt a no-phone-gazing-after-10-p.m. rule) and my face is lavished in calming botanicals, I cozy up to my Casper to follow Huffington’s advice on sleeping with a snorer. “If trying to get the snorer to stop doesn’t work, you can try changing how you react to snoring,” she says, recommending that one learn to enjoy the sound of it. The attempt to pretend that this nasal soundtrack is as mellifluous as, say, the sound of a Mozart clarinet concerto is exhausting and one I decide to put to bed. But that particular failure aside, a few weeks into my new sleep regimen, I will admit that I am feeling and sleeping better than I have in years. I’d prefer not to consider just how many years (counting years is not like counting sheep) — I can’t afford to lose any more sleep.