In 2011, my younger brother Lee was stopped and frisked on his way to buy ginger ale at the grocery store on 216th Street and White Plains Road.

Walking into the market, his black du-rag on and headphones plugged in, two white police officers stopped Lee and asked to search him.

“What’s the problem?” he asked, looking back and forth between the officers, his heart rate starting to rise. “Why are you stopping me?”

The officers told him he fit the description of someone they were looking for before starting to pat him down. Moments later Lee was pressed against the wall and handcuffed for (legally) carrying a small pocket knife for protection.

Hours went by before my older brothers and I received a call that Lee, then 18, had been arrested and was being held at the 47th precinct in The Bronx. He came home with us that night in one piece—the pocket knife they’d arrested him for was within his right to carry. But I still think about all the things that could have gone wrong with his arrest. What if the officers had decided to put him in a chokehold? What if they had decided to knee his neck until he stopped breathing? What if he made even the shadow of a gesture that could be perceived as resisting arrest, and they shot him right where he stood? Police misconduct like this happens so often to Black men, and goes unpunished just as often.

When the dead man is a Black man, it’s as though it matters less. Especially now, when we live under an administration that revels in bending and breaking laws in support of the white man.

Since Lee’s unjust arrest nine years ago at the height of stop-and-frisk, when 9 in 10 New Yorkers who were stopped and frisked were innocent and disproportionately Black and Hispanic men, there’s been an unending list of wrongful killings and shootings of Black people by police officers and white citizens. The color of a Black man’s skin has become so weaponized that just walking down any street in America makes them a threat.

In 2019, Black people made up 24% of those killed by police, though they only make up 13% of the American population. Black people are three times more likely to be killed by police officers than white people. Since 2013, 99% of the killings of Black people by a police officer has not resulted in the officer being charged.

This means that in 2016, when 37-year-old Alton Sterling was shot six times at close range by Baton Rouge Officer Blane Salamoni outside a convenience store, Salamoni faced no criminal charges. Or, when 12-year-old Tamir Rice was shot twice in 2014 by Cleveland Police Officer Timothy Loehmann, he too faced no jail time.

And it means that when 43-year-old Eric Garner died from being held in a chokehold by then-NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo in 2014, Pantaleo also went un-charged. Even when potentially damning documents were released in 2019 about Pantaleo’s prior violations, Attorney General William Barr decided not to pursue a federal civil rights indictment against him. It took five more years before former NYPD commissioner James P. O’Neill fired Pantaleo.

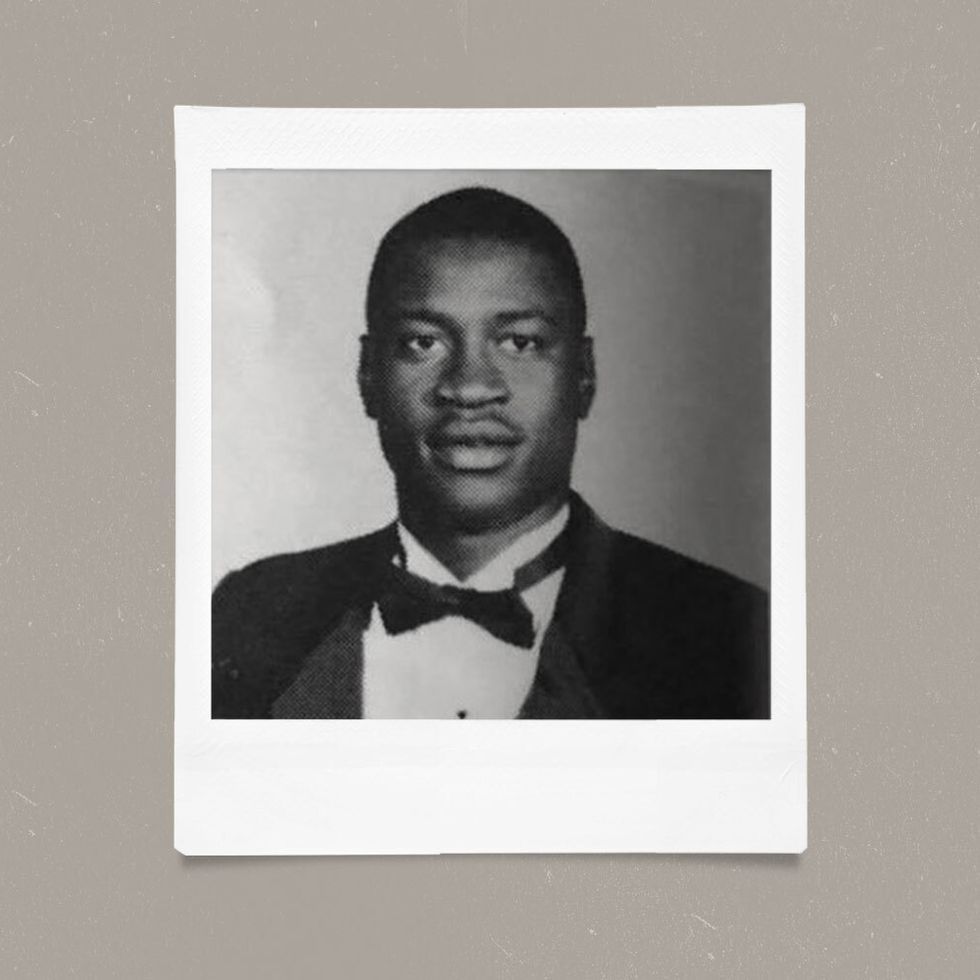

In 2020, Garner’s chilling dying words—“I can’t breathe”—remain resonant. On Monday, 46-year-old George Floyd uttered them again, with his head pressed against the pavement of a Minneapolis street, a white police officer’s knee lodged into the thickness of his neck. For more than seven minutes Floyd struggled to breathe and cried out for his mother, as Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin pressed against his airways and panicked bystanders begged Chauvin to stop.

The inevitable viral video of the encounter ends with Floyd’s lifeless body, hands shackled behind him, being wheeled into an ambulance. Why did this scene feel so familiar to me, as I watched it at home in the dark of my apartment? Watching George Floyd cry out for his mother—his pain was palpable. Each video of police brutality is different— the Black men in them have different names and come from different places and yearn for different things—and yet somehow the outcome is always the same.

My four brothers could fit many descriptions of an African-American man detailed over a police radio, be it in a park, in a gym, or just walking down a street others believe they don’t belong on. This is America in 2020: every time my brothers leave the house I have to worry if they will come home at all.

It’s exhausting. How many hashtags will it take for all of America to see Black people as more than their skin color? Is this what a Black man has been reduced to: a retweet of a Black Lives Matter account, a Like on a friend’s outraged Facebook post, a colored pencil portrait of the victim shared to Instagram?

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

James Baldwin famously said, “White is a way to describe power.” I’ve never felt and recognized the meaning of those words more than I do in today’s increasingly polarized society. Every week seems to bring a new heartbreak to reckon with as desensitized viewers spread footage of Black death across social media in the name of “allyship.” Someday I hope the likes, hashtags and retweets lead to the convictions of whites who’ve worn their skin as their power for far too long. Until then—perhaps even then—I’ll worry every time my brothers step out their front door.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io