“Why can’t you read?” It was spring 2020. The interrogator was my daughter, who was three at the time. My parents, Chinese and Taiwanese immigrants who came to the U.S. in the 1970s, had gifted her the picture book Guji Guji by Chih-Yuan Chen, which is about a baby crocodile who believes he’s a duck and joins a family of ducks. Hijinks ensue. It’s a tale of acceptance, belonging, and family. Though this version contains an English translation crammed onto the last few pages, all the fun illustrations are in the body of the book, where the story is written in Chinese characters.

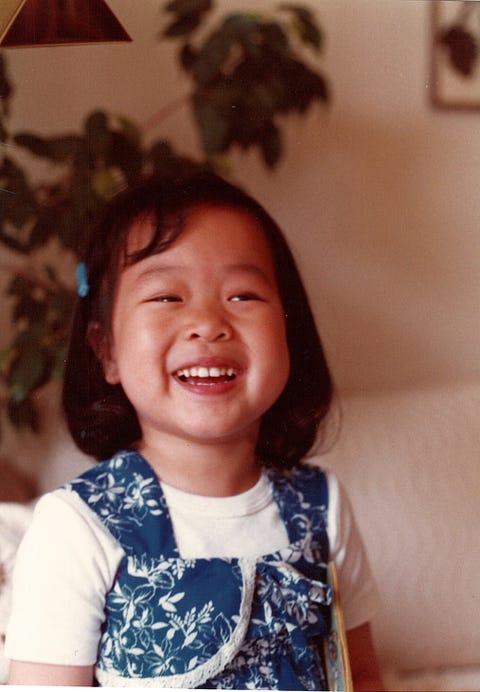

I’d like to tell you that I could once read the book in its original language, but actually I never could, despite two valiant years of Chinese courses in college. But as a child, I would have understood the story being read to me, say by my parents or grandmother. At my daughter’s age and through elementary school, I was bilingual. My parents and maternal grandmother spoke to me almost exclusively in Mandarin. I could carry on my side of the conversation. I didn’t feel lost in Mandarin, as I do now.

I can think of no better example of my immigrant daughter language shame than being required to tell my toddler that I can’t read Chinese characters, can barely speak Mandarin, that this book would have to be read to her by her grandparents. We’d have to wait until their next visit. After that conversation, I turned down many requests to read Guji Guji at bedtime, sometimes going so far as to hide it behind other books, feeling each time not only like a bad Chinese daughter, but also a bad mother.

The stories I can share about my struggles with my family’s native language are probably ones you’ve heard from other first-generation kids. I could barely converse with my paternal grandmother, who lived with my family, since she spoke a regional dialect that had little overlap with Mandarin. When I’ve traveled in China with my parents, my language skills have been critiqued by pretty much everyone, including taxi drivers and store clerks. One memory stands out: my very first trip to Beijing in 2001, when I was in my early twenties and my sister was in college. We were at a dinner with my mother’s extended family. A distant relative (seated across from the table, but within earshot) pointed at me and my sister, and while staring at us like we were curious zoo animals, said to another relative: “This one can understand and speak a bit, but the other one can’t understand anything.” We sat there humiliated, able to understand every word, but unable to defend ourselves. When my sister and I returned to our hotel room that night, we wept.

These days, my deteriorating Mandarin doesn’t bring me to tears, but the pain nags at me and flares up during every conversation with my parents, when I’d like to reply in Mandarin, but can’t find the right words. I’ve never talked about it as an adult with my sister or parents. But it’s always there, a steady hum of guilt, a feeling that I could have done better, tried harder, that if I had better priorities, I’d study the language all over again. I compare myself with other ABC (American-born Chinese) kids who remained bilingual. I compare myself with my cousins, who are all much more fluent.

I don’t know exactly when my fluency started fading. Perhaps when I was in junior high. Perhaps high school. As life became more complex, I didn’t learn the Mandarin vocabulary to meet and express that complexity. In college, I tried to read and write the language for the first time. My grades were decent, but all the characters I memorized left my brain as soon as each semester’s final was over. Nowadays, I have to remind myself how to write my Chinese name, or Mama or Baba. My parents and I speak Chinglish: They mostly speak Mandarin, I mostly reply in English, and together we combine words and phrases from both languages. When my husband is present, we all speak only in English. Speaking in English is more comfortable. I’m a more interesting person in English. A novelist. A thinker. A person with things to say.

Why do I feel so guilty? I feel like I haven’t held up my end of the bargain. After establishing our family in America, in one generation, my parents’ native language is disappearing. I don’t think this is what my parents intended, even though they’re very proud of who my sister and I have become, and they would never guilt us about our speaking skills the way extended family and strangers have. Still, I feel like I’m disappointing them, that I’m disappointing my late grandmothers. Language is heritage. It’s a way to hang onto the way I was raised. I’ve always felt more Chinese than American, even though I was born here. Perhaps I’d feel less conflicted if Asians were regarded as “real” Americans, but since we’re not, I cling to my Chinese identity. I worry about this identity fading as my biracial daughter grows up. What will be left of our Chinese heritage by the time she’s an adult?

I certainly can’t blame my parents. They never insisted we only speak English, as some immigrant families have done in order to assimilate. My parents met in the U.S., in graduate school. They had to be bilingual in order to succeed as college professors. They’re both terrific storytellers and conversationalists in both languages. If they feel embarrassed by my clumsy Mandarin, they’ve never said so, and for this I’m grateful, though I also wish they’d sent me to Saturday Chinese school as a child.

I always thought that if I had a child, I’d speak Mandarin to that child and pass on the language, as my parents did for me and my sister. It’s been impressed upon me by the world at large that I should teach her, because it’s easier to learn a second language at her age. However, I only speak what I call “kitchen Chinese” with terrible grammar and the simplest vocabulary. I can talk about the weather and food and express basic emotions. I have so little to pass down. It turns out that making one-sided conversation with a small child in a language in which you’re not fluent is difficult. At first, I tried harder. I wanted her to hear a little Mandarin each day and would chatter to her at bedtime. But once the pandemic began, I lost any energy I had for this extra effort.

A nicely illustrated English translation of Guji Guji exists. I’m embarrassed to admit that it didn’t occur to me to look for this version until I started writing this essay. It was easier to put the book away and not think about it. I told myself that teaching my daughter Mandarin and shoring up my own language skills would be things I’d tackle when I had more time. Instead, I’ve been a nuisance to my parents, nagging them to speak in Mandarin during phone calls, when they just want to have a conversation with their granddaughter, not teach her another language in ten minute increments.

As the months in quarantine dragged on, Guji Guji came to be a regular reminder of how much I missed them. My daughter and I would talk about reading the book “when we see Gonggong and Popo again.” Ultimately, being extra cautious, my husband and I decided not to drive to Chicago to visit my family. My daughter changed dramatically, as all toddlers do, and my parents only saw those changes on FaceTime. By the time they were vaccinated and came to see us in Philadelphia, they hadn’t seen her in about 18 months and were so amazed by her speaking in complete sentences that they barely spoke to her in Mandarin at all.

This past September, my daughter, who is almost five, began attending a Mandarin-immersion program at a local Montessori, a program that certainly didn’t exist when I was growing up in the 1980s. My hope is that she’ll eventually become proficient enough to converse with my relatives and interested in learning the language throughout her life. I want her to be proud of being Chinese. I want her to have a foothold in the language. It’s humbling to have teachers do the job that I can’t, and in fact, upon first meeting, I had to tell her teachers that no, I can’t read the signs in the classroom. But part of being a good parent means accepting my limitations. I needed help with teaching my daughter Mandarin and luckily found this school. Even if she doesn’t become fluent, I hope it will mean something to her that I tried.

Though I’m unlikely to ever read Guji Guji to my daughter in Mandarin, we recently moved back to Oak Park, Illinois to live near my parents, where this school is an added bonus. There’s such comfort in being able to simply see each other again, to have them watch their granddaughter grow up. My parents even requested that I purchase the same Chinese instruction books being used at my daughter’s new school, so they can do extra lessons and help her catch up. I’ll be trying to catch up too.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io