Decades before Fleabag snogged a priest, before a Snuggie-wrapped Liz Lemon dined on night cheese, and before Lena Dunham sat naked in a bathtub eating a cupcake on Girls, Aline Kominsky-Crumb was bringing the messy interior lives of women to life in her comics.

As an underground comics artist in the 1970s, Kominsky-Crumb pioneered a style that was equal parts confessional and caustic, deeply honest, and darkly funny. Unapologetically autobiographical, her work has chronicled her stifling childhood on Long Island, her first sexual encounter as a teenager (and her many subsequent run-ins, both good and bad), and her relationship with everything from wine to wrinkles to Robert Crumb, her famous cartoonist husband. Her work is unflinching and radical, and paved the way for generations of artists to tackle what it means to be a woman, without a filter.

“At the time when I was doing it, it was just what I wanted to do. I didn’t think about it [as pioneering] at all,” said Kominsky-Crumb, speaking by phone from the village in the South of France where she’s lived for the past 29 years. It’s taken a more recent outpouring of adulation from younger artists, she says, but now, “I do realize that I was a trailblazer.”

Kominsky-Crumb, 72, is the subject of a solo exhibition at Kayne Griffin Corcoran gallery in Los Angeles, running through May 9. The show opened in the gallery’s physical space just as the rapid spread of COVID-19 wiped out group gatherings and much of public life. Luckily, the show lives on digitally through an online viewing room, where all 19 of the works can be seen from the safety and comfort of home.

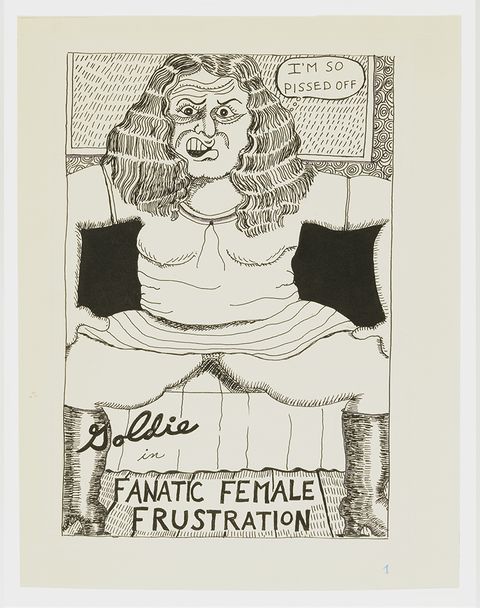

The exhibit features works spanning her prolific 50-year career, including mixed-media drawings alongside her comics. Her signature black-and-white scratchy cartoons can provoke a strong reaction, but they’re also unexpectedly warm, in the way that it’s comforting to see submerged parts of yourself finally laid bare. Kominsky-Crumb’s work also feels relatable in its raunchiness, especially now that most of us are homebound, horny, and desperate for distraction. Be honest: Whom among us hasn’t wondered how many calories are in a cheese enchilada while sitting on the toilet?

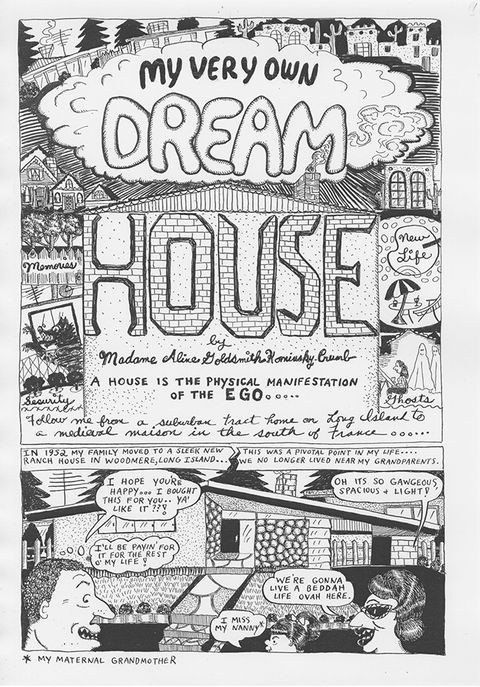

A highlight of the show is “Dream House,” a 30-page cartoon that traces Kominsky-Crumb’s life from her miserable childhood in a middle-class Jewish household on Long Island through her meeting Robert and relocating to France along with their daughter Sophie in the 1990s. The depiction of her upbringing, especially her parents, is brutal.

“I was really anger-motivated. I had to get that stuff out,” Kominsky-Crumb told ELLE.com. Growing up, she never felt like she fit in—she was always too big, too Jewish, too poor. “I was very much an outsider and I developed a critique of that world at a very young age,” she says.

“Dream House” also traces Kominsky-Crumb’s escape from Long Island to New York City, where she took art classes and leaned into the freewheeling, bohemian lifestyle of the 1960s. She stopped shaving, experimented with free love and drugs, and felt alive.

“I was a real hippie,” she says. “It was very anti-bourgeois and anti-establishment.”

That ethos changed her art forever. “My desire to do comics was, instead of doing art for rich people, I wanted to do art that people read on the toilet,” Kominsky-Crumb says. Her disdain for the “elitist and horrible” art scene in New York drove her to leave Cooper Union, where she had been studying, for the University of Arizona. After graduating in the early 1970s, she headed north to San Francisco, the focal point of the counterculture, where she developed her style as a cartoonist in a time when there were very few other female cartoonists. Soon after she arrived, she found a women’s art collective that was putting together one of the first feminist comics produced entirely by women, called Wimmen’s Comix, and started contributing. The collection dealt with topics that were still quite radical at the time: abortion, queer life, rape.“It was like we were inventing a new profession for women, and a new voice for women,” Kominsky-Crumb says.

In 1971, she met Robert “R.” Crumb, who was already an established underground cartoonist lauded for his satirical, highly detailed comics. Their partnership would have a lasting effect on Kominsky-Crumb’s work, and the two have collaborated on various comic strips and books over the course of their decades-long relationship.

After a few years of contributing to Wimmen’s Comix, Kominsky-Crumb split from the group in 1975. Some of her work around sex and bodies had been deemed too demeaning (one of her early comics, “Bunch Plays with Herself,” features her alter ego Bunch picking her butt, popping a pimple, and masturbating). Her relationship with Crumb (who has faced criticism for his depictions of women, violence, and racial stereotypes) also didn’t sit well with some of the hard-line feminists at Wimmen’s Comix, so she and the other “bad women” of the group, including cofounder Diane Noomin, started a new women’s comic called Twisted Sisters.

Now she had carte blanche to be as vulgar as she pleased. But don’t mistake her work as crass for crassness’ sake—much of her work is about seeking the approval that evaded her in childhood, grappling with her own insecurities, and the broader expectations society foists on women. “On a deeper personal, psychological level, I realized it was like, ‘Okay, I’m disgusting, will you still love me?…I have zits and warts and I smell and everything like that. Will you still love me?’”

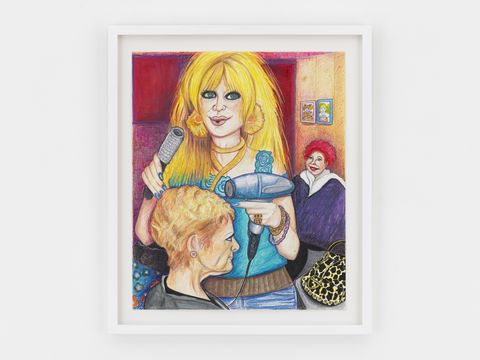

Also on view in the exhibition are colorful portraits Kominsky-Crumb drew of her mother’s hairdresser, Cookie, and the friends she made after moving to Florida. The hair is big, the nails long, the jewelry stacked. “[Cookie] was such an unbelievable character. I would always go down and hang around with my mother in [the salon], and these women would come in and they’d want to tell their whole life story,” Kominsky-Crumb recalls. “They needed to confess. And I would sort of become invisible because I would be in there drawing and stuff. They would just tell me their whole life stories.”

Kominsky-Crumb realized that in a lot of ways, those women could have been her. “I was raised to be like them and part of me is like them,” she said. Camaraderie and empathy run through the caricature of these portraits. “They’re critical, at the same time, there’s a bit of admiration, so I try to tread that line.”

As she’s gotten older, her subject matter has kept pace, with stories about turning 40, becoming a grandparent, and dealing with a receding hairline. One panel in “Of What Use Is an Old Bunch?” from 2013 lists the cosmetic enhancements she’s turned to, including teeth implants, hair extensions, and Botox—all with zero apology.

Whether it’s her portraits or comics, Kominsky-Crumb’s work still feels radical this many decades later for the way she turns taboos into cultural commentary simply by calling our attention to them. Women are nothing if not complex creatures. We fart, we eat, we fight, we have sex—and we have all kinds of feelings about all if it.

These days, Kominsky-Crumb cares less about shock. She’ll leave that to the new guard of provocateurs, like Dunham, whose work she said makes her own look “mild.”

“Maybe I broke through on one level, but where people have taken it now is unbelievable,” she reflected. After surviving colon cancer, Kominsky-Crumb now spends much of her time doing yoga and spending time with her grandchildren in her adopted French hometown. She still works on the occasional story—a collaboration with R. Crumb on a certain president is forthcoming—but it’s on her terms. “I’ve evolved my own style over the years,” she says. “I’m not in rebellion of anything anymore.