When 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in police custody this September after allegedly disobeying Iran’s hijab law, Marina Nemat had an unshakeable feeling: Amini’s fate could have easily been her own. In 1982, Nemat was just 16 when she was arrested in Iran under charges of speaking out against the regime, and she spent two years in Tehran’s infamous Evin Prison before she was able to escape. Now fatalities in Iran are rising, as the police attempt to suppress the mass protests that have been going strong for two months since Amini’s death, and Nemat has been on edge. But she also feels a sense of relief that the world is finally focusing on her home country. “It’s a far cry from when thousands of women—and men—were imprisoned, tortured, and executed during my time,” she says. “We felt like what happened to us was invisible to the rest of the world.”

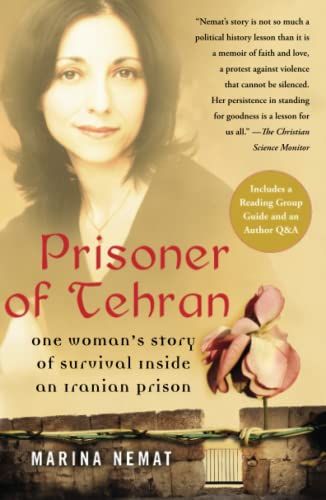

Even Nemat’s story has been in the news since Amini’s death came to light. Nemat wrote about the ordeal in her 2007 international bestseller, Prisoner of Tehran: One Woman’s Story of Survival Inside An Iranian Prison, which delves into the details of her incarceration, her near-execution, and the hardships she endured even after she left prison. “Writing the book was a way to process and manage the pain because otherwise I would have gone crazy,” she tells me by telephone from her cottage outside Kingston, Ontario. “The trauma was like a noose around my neck and it kept getting tighter.”

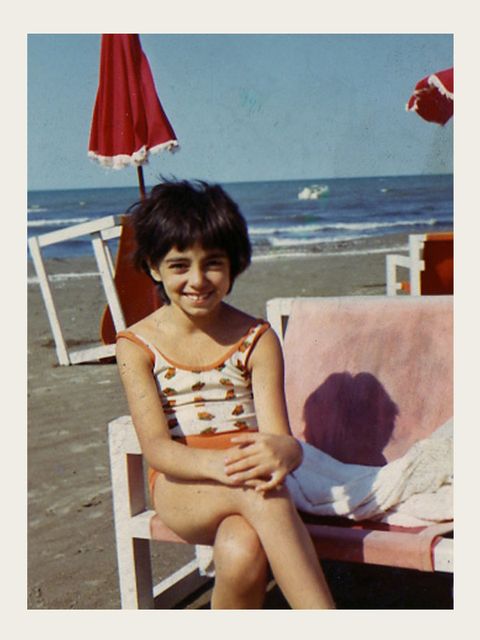

Nemat grew up in the ‘70s during the much more liberal era of the Shah, a secular monarchy backed by the United States, that had placed the country on a trajectory toward modernization and westernization. “I had a green bikini with white polka dots, and I would be on the beach with absolutely no problem,” she says. “Boys and girls would hang out together, and we would dance to Donny Osmond and The Bee Gees until two in the morning.” Then, after the Iran Revolution in 1979, the hijab law was introduced, requiring women and girls above a certain age to wear a headscarf in public. “In the beginning, they said you had to wear it inside government offices, but then it spread to schools and everywhere else. In my time, the clothes for women had to be very baggy; you couldn’t show any curves whatsoever.” Nemat recalls her principal, who was also a revolutionary guard, standing at the door of the school armed with a washcloth. “If she suspected so much as a hint of lip gloss, she would scrub your face in a bucket of water.”

Nemat was always the one student who questioned the status quo. “I was a loudmouth and made myself heard,” she says. “There were teachers who were turning math and chemistry classes into lectures on enforcing the hijab laws or studying the Koran. I would be the one who would dare to stand up and say, ‘Why should we dress this way?’ or ‘Why are we talking about religion and political propaganda when this is supposed to be a math class?’” When a teacher told her to leave the room if she didn’t want to participate, Nemat was surprised to hear the whole class walk out behind her. Although she wasn’t part of any political groups, she had attended rallies and written articles in the school newspaper on the anti-revolutionary protests that she witnessed in the streets. A friend and her brother, who was part of the Mojahedin-e-Khalgh leftist Muslim group, had both been arrested. So was her best friend Shahnoush, who had no affiliations with anything anti-revolutionary. “Shahnoush was totally harmless,” she says. “I was more the troublemaker.” Nemat’s own worries about being on the police’s radar were confirmed when her chemistry teacher told her that her name was on a list in the principal’s office.

Nemat was arrested at 9 p.m. on Jan. 15, 1982. In her memoir, she says that she wasn’t afraid—perhaps because she had been expecting it—but that the feeling was more like a “cold void that surrounded her.” She stood out to the guards at Evin because she didn’t seem worried about herself; instead, she comforted the other girls. Nemat also didn’t cower before the interrogators. Her responses to questioning were always matter-of-fact, even blunt. Her feet were beaten by men with cables because she refused to give up the names of any anti-revolutionary or Communist-leaning classmates.

One night early on in her incarceration, Nemat was blindfolded and driven to what she calls “the middle of nowhere” and found herself in front of a firing squad. “A cold feeling inside my chest paralyzed me,” she wrote in the book. Suddenly a guard, whom she calls Ali, appeared with orders to save her. While Ali had been able to use his political connections to downgrade her sentence to life in prison, it soon became apparent that his efforts to halt her execution were self-motivated. He told Nemat that she could be released from prison altogether if she would marry him, and that she could get a significantly reduced sentence under his care. Marrying Ali also meant that she would have to convert from Christianity to Islam. The proposition could hardly be considered a choice, because the alternative meant that her parents and Andre, the organist from her church she had feelings for, would face either imprisonment or death. “[Ali] had saved my life, but he made me suffer in another way, and I can’t forget that,” she tells me. Months into the marriage, Nemat became pregnant but miscarried when Ali was killed in front of her by rival factions from within the prison in a drive-by shooting.

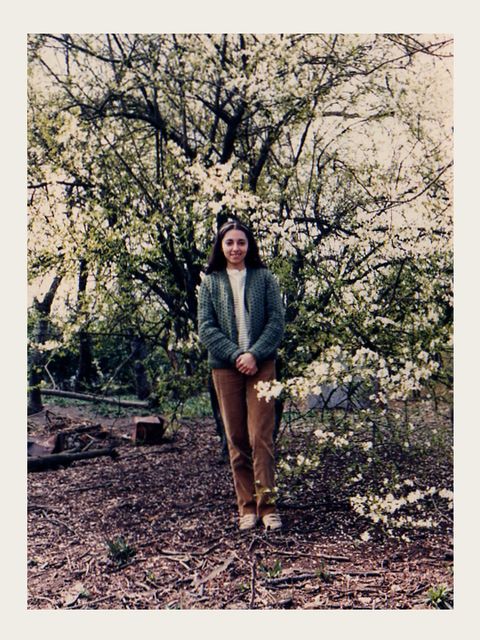

After Ali’s death, Nemat was returned to Evin Prison, but Ali’s father mediated for her release, and she was returned to her parents. When she was given her freedom, Nemat was warned not to marry Andre, because as a now-Muslim woman, she was forbidden to marry a Christian or else she’d be imprisoned or executed. She decided to anyway. “I think I was desperate to prove to myself that I was the same person before Evin and that it would be possible to continue my life as if nothing happened,” she says. “Even if I was putting myself in danger, I needed to believe that what had happened had just been a hiccup in my life.”

In 1991, Nemat and her husband were able to secure visas for Canada and leave the country. They spent the next decade building a home in Toronto. It was then, during what should have been the most stable period of her life, that her past started closing in on her. She lost her ability to sleep and flashbacks of upsetting memories invaded her mind the minute she went to bed. Nemat knew that she had to allow herself to remember and record everything she’d experienced in Iran in order to move on. She also volunteered for the Canadian Centre for Victims of Torture, and she learned about memory work and how to manage her symptoms. “I have PTSD, but it goes through remission,” she says. “On a normal day, I won’t have any symptoms, but if I get terribly stressed, I’ll get recurring nightmares. I’ll also get ridiculously emotional at the drop of a hat.”

Nemat draws a disturbing parallel between Mahsa Amini’s arrest by the morality police and her own incarceration 40 years earlier. When Amini was arrested, her family was reportedly told she was being detained for “re-education” and would soon be released. Similarly, Nemat remembers the people in charge at Evin referring to the prison as a university. “They said that we were all to be re-educated and brought in line with the Islamic Republic,” she says. “So anything to do with the idea of ‘re-education’ terrifies me, because I know what it really means.”

But she also sees herself in the courage of Iranian women who have been rebelling against the regime since Amini’s death and the women who stood up during her own time. “Iranian women have always been very bold. When I was attending protest rallies, there were a lot of women who were unafraid to risk their lives for what they believed in.” She says the young women in today’s Iran were born after the Revolution, so they never got to experience some of the freedoms she did, such as the right to wear what they want. Contrary to the West’s perception, Iranian women are very modern, she adds. “When they go to family functions or dinner parties, they wear the latest fashions, but in public they have to look a certain way. They are forced to live this double life.”

Strict enforcement of the hijab laws also tend to happen in waves, she says. “You can have times when the morality police won’t bother you much. Since my time, I see that sometimes the clothes, although completely covered, have been tighter. Sometimes headscarves would be smaller, where some of the women’s hair was visible. Or the morality police wouldn’t care about a little makeup or nail polish or if your headscarf slipped off your head a little.” At the same time, the following week could bring forth a torrent of arrests, she adds. “It was always very unpredictable. Of course it also depends on the president of the time. [Now-]President Raisi has made the hijab laws more rigid.”

Iranian women know what they are missing, Nemat emphasizes. “They are extremely resourceful and see how they have it compared to the rest of the world.” Even though the government tries to control internet access, it fails, she says. “It’s thanks to the brave Iranians who have been posting or sending videos of the protests that the plight of the Iranian people—particularly women—is finally getting the attention it deserves.”

Even so, Nemat doesn’t know if the mass protests mean that the country is witnessing the makings of a revolution. “It could be, but if it is, I worry about what would take its place. The brutality of the government seems worse now, and they are not afraid of torturing or murdering masses of their own people.” Just this month, a majority of the Iranian Parliament signed a letter calling for “harsh punishments of protesters,” according to Newsweek.

Today, Nemat is a writer and teacher of memoir writing at the School of Continuing Studies at the University of Toronto. It’s impossible for her not to periodically look back and ruminate on how her life could have gone so many different ways—especially when women like Amini are proof of that reality.

“I am still shocked that I am alive,” she says. “Many of my friends were killed. My best friend was executed three months before I was arrested, and I think about her every day. Just the other day, I was taking in the fall foliage surrounding my cottage, which is a little place in the woods by a small lake, and wondering how I got here.”

Wendy Kaur is a Toronto-based lifestyle, beauty and fashion writer whose work has been published in British Vogue, ELLE Canada, InStyle, FASHION, FLARE, and others.