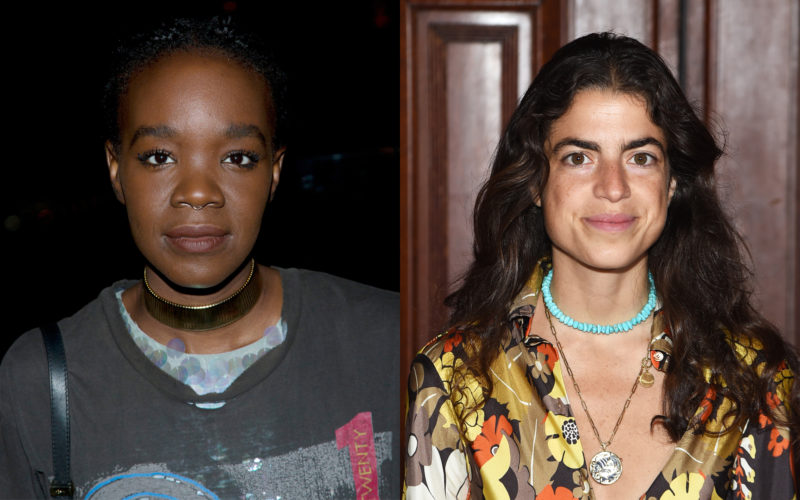

Podcast host Recho Omondi has apologized for using antisemitic slurs in a recent interview with Man Repeller founder Leandra Medine Cohen. We spoke to experts about why the comments were damaging.

Designer Recho Omondi launched the fashion podcast The Cutting Room Floor in 2018, and has since used the platform to tackle important topics in the industry. From myths about recycling clothing to the necessary evolution of designers, each episode is packed with Omondi’s signature well-informed fashion commentary. The podcast is beloved by listeners but not widely known, with it averaging 10,000 listeners per episode, according to The Business of Fashion. This is why it was surprising to some that Leandra Medine Cohen, founder of now-ceased fashion publication Man Repeller, chose Omondi’s podcast for her first interview about shutting down the site.

The episode containing the Medina interview, “The Tanning of America,” was released on July 7. The episode touched on Medine Cohen’s decision to end Man Repeller abruptly last year, the backlash she faced for pandemic layoffs (one of which was to a senior Black employee) and the alleged hostile work environment at the publication. “The Tanning of America” has garnered new levels of attention for The Cutting Room Floor — this time, because of its casual yet unmistakable antisemitism.

The podcast episode focused on Medine Cohen’s privilege, with quotes of her saying that growing up, she thought she was on “the brink of being homeless” until she realized last summer that she had always been wealthy. This felt particularly tone deaf at a time when many people are actually facing homelessness, and her decision to suddenly shutter Man Repeller left some of her employees without a job in the middle of a global pandemic. Her statements circulated around the internet, and some media outlets responded with pieces like one that came from The Cut titled Upper East Sider Realizes She’s Privileged. In short, the interview did not go well.

The episode’s conversation was broken up by Omondi’s personal narrative dialogue, where she made some comments about Medine Cohen as it relates to her being Jewish. She started off the podcast by saying, “This country was founded by racist white men, and for the purpose of this episode it’s important to note that many of those white men, slaveowners, etc., were also Jewish and also saw Blacks as less than human.”

At the episode’s end, Omondi used Jewish stereotypes to argue that Medine Cohen has not been oppressed. “I couldn’t stomach another white assimilated Jewish American Princess who is wildly privileged but thinks she’s oppressed,” she said. “At the end of the day you guys are going to get your nose jobs and your keratin treatments and change your last name from Ralph Lifshitz to Ralph Lauren and you will be fine.”

Ben Sales, a writer for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, wrote about his reaction to the podcast on July 12, saying he was surprised at how “her interview was bookended by antisemitism.”

“The language Omondi used jumped out at me right away,” Sales tells FASHION. “Her false claim about Jewish slave owners has been debunked, and her comments on nose jobs and Medine Cohen being a ‘Jewish American Princess’ echoed age-old stereotypes about Jews being materialistic.”

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt, a Jewish journalist, also Tweeted her reaction to the podcast on July 12, pointing out that there were “antisemitic dog whistles,” and saying that Omondi “shamelessly equates Jewishness with wealth, power & privilege.” She called out publications for not including this in their initial coverage of the episode.

The day after the podcast was uploaded, Omondi posted to her Instagram Story: “I want to recognize that I understand Leandra does not represent ALL Jewish people or the vast culture whatsoever.” She added that she would block people who posted hateful comments about Jewish people on her account.

As criticisms surrounding her podcast remarks grew, Omondi edited and re-uploaded the episode without the antisemitic comments, and on July 20, she released an official apology via The Cutting Room Floor. In her apology, Omondi said she painted Jewish people with “one big, broad stroke” and that she didn’t understand the nuances of the culture. She said when using the term “Jewish American Princess,” she didn’t realize it was a slur and likened it more to the term “airhead.”

Anna Shternshis, director of the Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Toronto, says the prejudices enveloped in terms like “Jewish American Princess” are deep-rooted.

“’Jewish American Princess’ is an image of a young woman who is all about materialistic goods, who is only interested in financial benefits to herself, who doesn’t have genuine feelings, who is all superficial. [She is] very interested in her looks, but not interested in anything that goes beyond a strong position in the world,” she tells FASHION.

These stereotypes date back to when Jewish immigrants were struggling to assimilate to American culture at the end of the 19th century. As a result of their difficulties in trying to adjust, Jewish people used self-deprecating terms like “Jewish American Princess” as a way of “laughing at our own misfortunes,” Shternshis explains.

In her apology, Omondi said she appreciated those who called her out on her comments. “I’m not going to sit here and act like I know everything about Jewish culture because I’m learning about it, but, you know, I’m not ashamed to say when I fucked up. I’m not ashamed to learn more.” At the time of publishing, Medine Cohen has not responded publicly to the podcast episode or Omondi’s apology.

There are a lot of people who don’t know a lot about the Jewish community, and therefore don’t realize they’re perpetuating antisemitic ideas, says Sales. “There’s been a popular misconception in American society that all Jews are white and rich, which was never the case but which feeds into antisemitism,” he explains.

The situation ultimately serves as an important reminder of the unconscious biases we all hold. “I hope all listeners, Jewish and not, will take away that we all have blind spots, and all have more to learn about groups whose experiences we don’t share or fully understand,” says Sales.