Image Source: Courtesy of Jane Gershovich / OL Reign

Madison Hammond was the first person of Native American descent to play in a National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) game. That happened on Sept. 26 for OL Reign, and she’s still reliving it. “I’ve told everybody that I know I had so much nervous energy that all exploded in one ball of adrenaline,” she told POPSUGAR. Though there were countless thoughts running through her mind, she did have a moment where she realized the barrier she was breaking.

Hammond, who is Navajo and San Felipe Pueblo, said she felt herself losing her connection to her Native roots when she moved away from Albuquerque, NM, at age 9. It wasn’t until she entered college at Wake Forest University that she began to ground herself in those roots again. “A lot of Native American culture is derived off of beliefs and customs, and it’s almost like how someone connects with their faith or their religious beliefs,” she explained.

Hammond, now 22, said she used to wear a traditional necklace as a girl but stopped when she entered middle school. Once she got to college though, she made sure she wore a similar one given to her by her godparents under her clothes every day — it represents strength and power. It’s also for “protecting from bad thoughts and bad intentions,” and keeping her in a good headspace, she added.

“When I was in college, that was the first time that I was away from the natural protection of just being around my family and being around our traditions and our customs,” Hammond said. “And so I had to make a decision of whether or not I was going to continue that and own it, or if I was just going to shy away from it. I really wanted to get back to where I was when I first lived in Albuquerque, New Mexico.”

On top of that, Hammond would have conversations with family — her grandma, aunt, and mom — about Native culture. These conversations helped her come to the realization that she was “willing to say, ‘This is who I am. This is part of my identity. And I want to take that back just for myself.'”

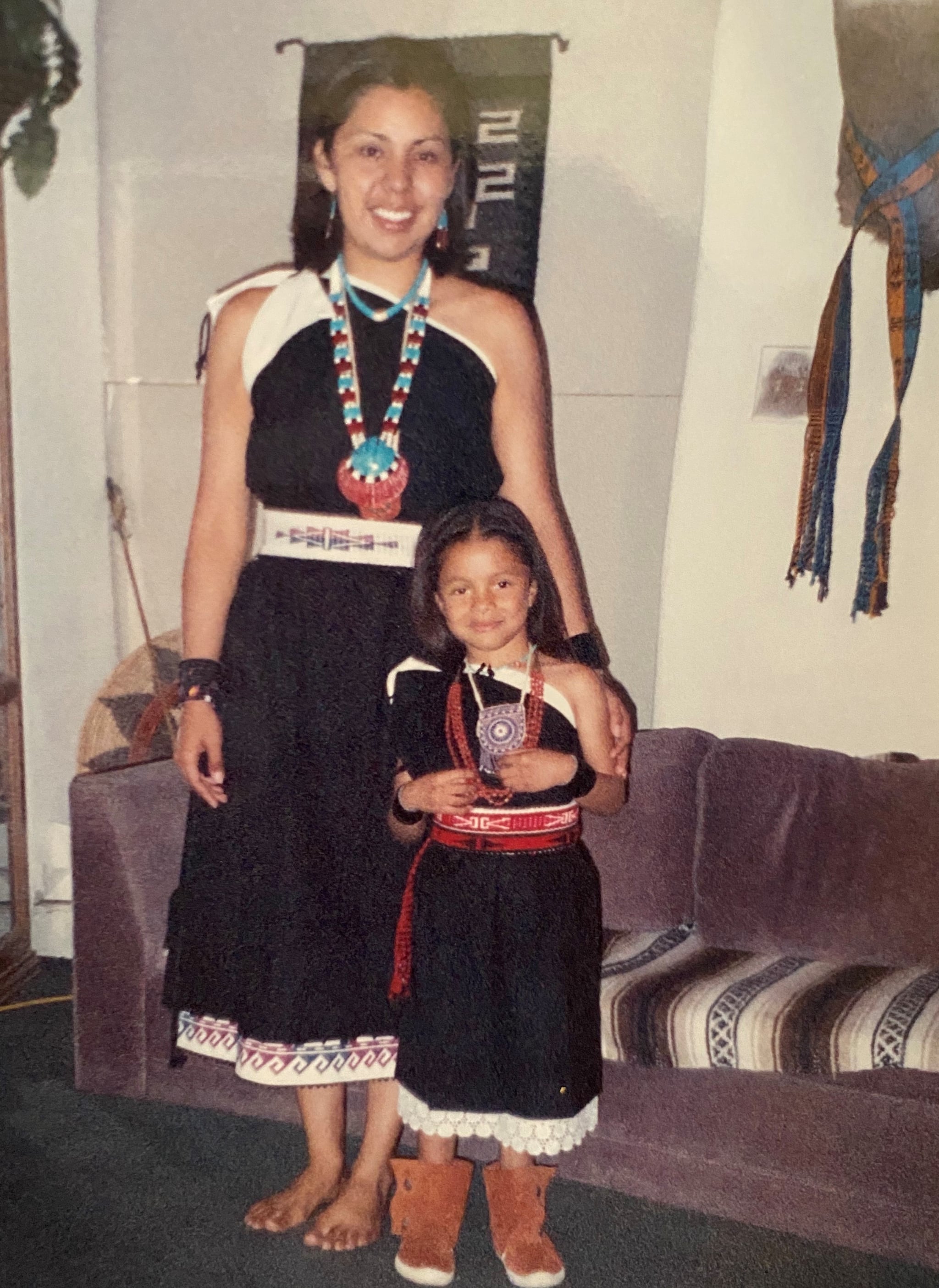

Photo: Madison Hammond with her aunt who still lives in New Mexico. Image Source: Courtesy of Madison Hammond.

When asked if there were any Native beliefs or ideals that she turns to when playing soccer, Hammond said there’s nothing explicit, but when she steps onto the field she believes her family is always there with her. “It’s not just me playing the game, it’s my family and people who have passed on. They’re all there for every game, and so that’s a lot of power. I just try to take that and know that they’re watching over me and making sure that I’m safe from injuries, safe from bad thoughts.”

College was an invaluable experience not just for the DI soccer — Hammond started every game and was a captain for two years — but for the strength it gave her. “I felt that I was able to establish myself and establish my voice in how I wanted to approach talking about race, social justice, and just how Black and brown people can make their voices heard in predominantly white spaces,” she said. She noted that she grew up in a very diverse area in New Mexico and attended a diverse high school when she moved to Virginia. “So, I didn’t realize how much I had taken that for granted, and the type of conversations that people had that were normal in high school were not normal in college,” she said.

“I think it’s unfair for people to idolize athletes and expect them not to use their public platforms for what they want their voices to be heard for.”

At Wake Forest University, a “large majority of the racial diversity is made up by the student-athlete population, but there’s not enough representation of student athletes on student councils and donor meetings and things like that,” Hammond stressed. As a member of the student-athlete advisory committee, she drafted a letter her junior year to the university’s president that called for more racial diversity and representation, and it turned into what she deems a productive conversation between the student-athlete advisory committee and him. (“I wrote that draft I think 30 times,” she recalled.)

“I want people of color that go to Wake afterwards to feel comfortable using their voices because their voices matter,” Hammond said. As a Black and Indigenous athlete now in the NWSL and with a public platform, she knows the importance of speaking about racial and social issues. “It’s finding the right balance between making my voice heard and not getting muffled. I don’t want people to turn off their ears,” she said. “Because I feel like there’s a lot of times when people are outspoken . . . especially, unfortunately, women . . . that others don’t want to listen. And so for me, it’s more ‘How can I still contribute to the fight for racial justice? How can I still contribute to the fight for gender equity?’ And it’s a big challenge.”

Hammond, too, is on board with the coalition of Black players that has formed in the NWSL this summer. They don’t have a name yet, to her understanding, but they did put their first statement out in August. “I did not realize how few Black players there are in the NWSL,” she said (at one point in 2019, there were 32 Black players listed on rosters, making up less than eight percent of the league). So, hopefully, she said, “it’s a way that, as a unified front, we can advocate for more representation from the top down.”

When asked what she would say to those who criticize athletes for speaking up about racism and social issues, Hammond was clear. “I always just think it’s funny that people are willing to take athletes as icons and transformative people when it suits them and when it makes them comfortable. But when athletes are willing and able to use their platforms, it’s like people don’t want to hear the stories anymore, and I think that’s unfair,” she stated. “I think it’s unfair for people to idolize athletes and expect them not to use their public platforms for what they want their voices to be heard for.”

Hammond hopes seeing her break barriers in turn breaks stereotypes. And she wants to make sure that her story is told in an authentic way, “so that when anybody looks at me, they can see me for who I am and know that I am representing Black communities, Native American communities and know that whatever stereotypes that they might have and whatever biases that come out of those stereotypes, those can get broken down.”